Aug 29, 2022

Trudeau's hands-off approach to inflation is becoming untenable

, Bloomberg News

Trudeau's inflation approach becoming untenable

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau faces growing pressure to help Canadian households offset surging inflation as he meets with his cabinet in Vancouver next week to set his government’s fall agenda.

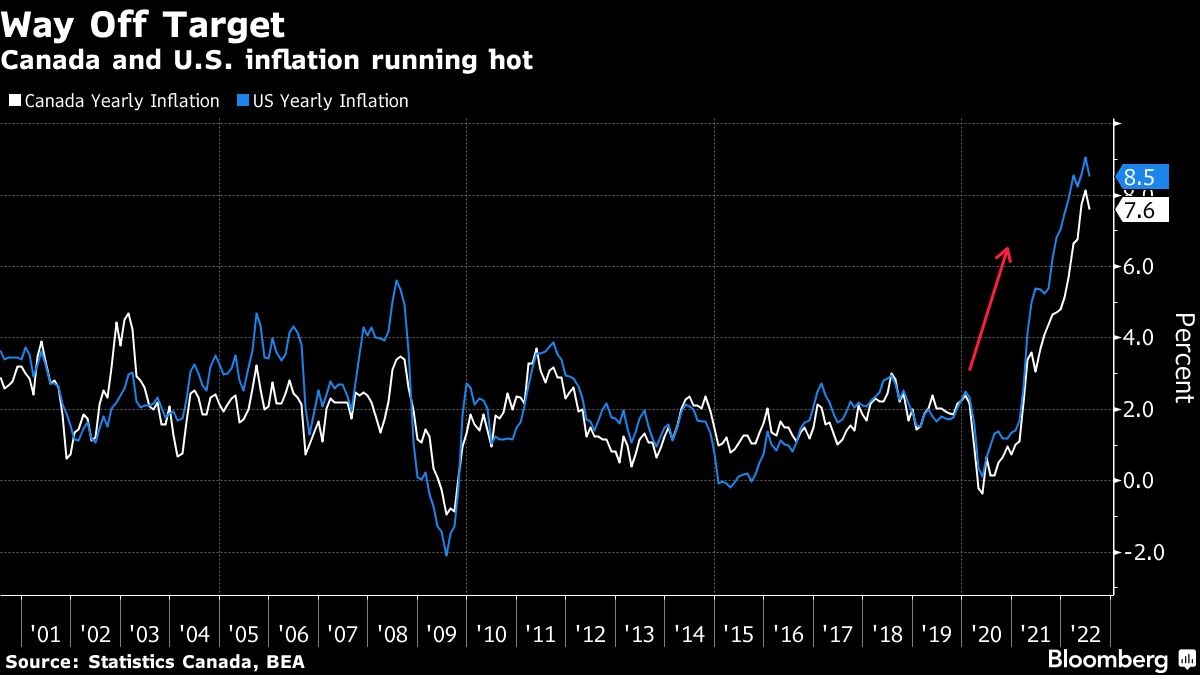

Unlike many of his global peers, Trudeau has avoided taking new measures recently to ease the burden of rising prices, even with inflation at its highest level since the early 1980s.

That may reflect a growing political sensitivity to criticism his government overspent during the pandemic, leaving the country with less fiscal room to tackle big future challenges like climate change. But there is also a wariness that doling out money to ease price pain may only wind up stoking more inflation.

Staying on the sidelines, however, has become increasingly difficult.

Trudeau is riding low in opinion polls after nearly seven years in power. And the likely election next month of Pierre Poilievre as new leader of the Conservative Party will add more urgency to the inflation debate. Poilievre has focused relentlessly on the cost of living during his leadership campaign, using the label “Justinflation” as he pins the blame on Trudeau.

“Politically, that fight is going to come to this government,” Shachi Kurl, president of the Vancouver-based Angus Reid Institute, said by phone. “It will come large and will come hard.”

Polling from Kurl’s research group found that four in five Canadians have been forced to cut spending in the face of rising costs.

In the absence of new measures from Trudeau, Canada’s provincial leaders have stepped in.

Ontario, the most populous province, temporarily suspended fuel taxes. Quebec’s premier, who began his campaign for a second term this weekend, is promising more direct inflation relief if re-elected. And oil- and fertilizer-producing Saskatchewan is sending out an “affordability cheque” to every resident this fall.

Canada’s economy is doing better than most, thanks to high prices for commodities, its abundance of energy and strong population growth. Worker shortages are widespread. That means the nation would probably struggle more than peers to absorb more government spending that adds to demand.

“I have noticed that other countries have been adding to their spending in recent months,” Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland told reporters last month after a meeting with her Group of 20 counterparts in Indonesia. “Canada has been restrained there as well, precisely because inflation is elevated.”

From a short-term fiscal perspective, the government can use revenue windfalls to pay for any new measures it wants to take. The most likely scenario is something along the margins, targeted to those who need it most and in line with the Trudeau government’s net-zero commitments -- so no blanket rebates for drivers filling up their cars with gasoline.

So far this year, the government has been pulling in billions more than anticipated.

National income -- the best indicator for revenue -- is on track to come in nearly $100 billion (US$77 billion) higher in 2022 than Freeland forecast in her April budget. That could mean as much as $15 billion in additional revenue.

For the first three months of the current fiscal year -- April through June -- the federal government ran a surplus, a surprise start given the $53 billion deficit projected for the year. The preliminary deficit for the fiscal year that ended March 31 was below $100 billion, versus $114 billion forecast earlier this year.

But it would be wrong to project those trends forward.

The last 12 months saw a rare confluence of strong growth in the real economy as the country emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic along with high inflation -- bonanza conditions for federal finances.

The next couple of years will be different. High inflation will inevitably act as a drag on the real economy. Economists expect growth to slow sharply, with some even forecasting a recession.

The impact from a weakening economy usually outweighs any potential tax-revenue gains from higher inflation. “Eventually, inflation is going to catch up to us,” said Mostafa Askari, chief economist at the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy at the University of Ottawa.

Add rising debt-servicing costs and it becomes a deleterious macro mix for Freeland’s next budget.

Yields on Canadian government 10-year bonds are currently at about 3 per cent, nearly double the average during Trudeau’s time in office. Freeland’s budget projections in April were based on assumptions the 10-year rate would be 2 per cent this year.

According to the finance department’s own analysis, a percentage-point increase in rates will drive up public debt charges by about $9 billion annually within five years -- or about equal to the yearly tab for Trudeau’s marquee child-care program.

Which means Freeland’s tone at next week’s cabinet retreat will be one of prudence and scaled-down expectations, even if there are new measures to stifle some of the political pressure.