Jan 6, 2022

U.S. Puts Thorniest Ukraine Issue Off the Table in Russia Talks

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- U.S. officials are pinning their hopes for common ground in upcoming talks with Russia on issues such as arms control, given President Vladimir Putin’s main demand for security guarantees to avert a potential war with Ukraine is already a non-starter.

With the clock ticking as Putin sends even more troops to the Ukraine border, the U.S. delegation led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman will come to Geneva this weekend ready to engage on the positioning of weapons in Europe, according to officials familiar with the administration’s thinking.

That narrow scope risks irritating her Russian counterpart, who says Putin wants progress within weeks on his calls for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to reduce its presence in Europe’s east and to agree to never admit Ukraine as a member.

The divergence heading into the talks highlights just how perilous the situation is, with the U.S. unsure whether Russia is even serious about wanting to negotiate. Moscow publicized the full list of Putin’s demands in the face of a U.S. request to keep them private, a move which has only added to that uncertainty, the people said.

Read more: Ukraine’s Army Is Underfunded and Not Ready to Stop an Invasion

More broadly, President Joe Biden and his top advisers currently have no idea if Putin really intends to invade, the officials added. The most recent call between the leaders on Dec. 30 didn’t shed any light on that, two of them said. Russia has shown no sign of de-escalating, other officials said, and is ramping up its efforts to target Ukraine with disinformation.

So when Sherman meets with Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov on Monday, it could prove an exercise in airing grievances and getting agreement to at least keep talking, as much as discussing terms.

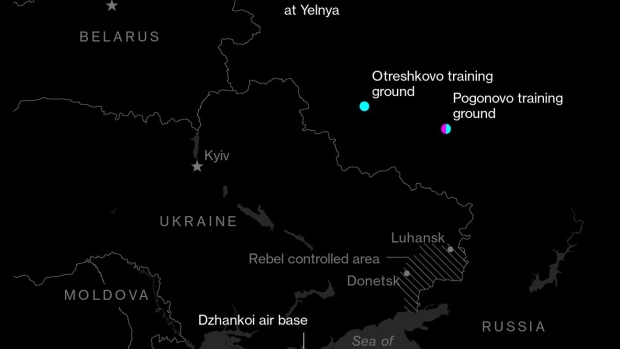

Intelligence assessments and satellite images show there are now more than 100,000 Russian troops in the vicinity of Ukraine, which indicates Putin is not willing to let the diplomatic process run indefinitely. Maintaining soldiers, tanks and other equipment there is expensive, and the terrain is likely to turn muddy again around March, making an incursion trickier.

“It’s very hard to make actual progress in any of these areas in an atmosphere of escalation and threat with a gun pointed to Ukraine’s head,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said Wednesday.

Still, he added, “I believe that if Russia is serious about pursuing diplomacy and de-escalation that there are things that all of us can do relatively quickly to build greater confidence.”

As the Americans parse Putin’s demands, there are some potential areas for discussion, officials say. One is his insistence on a pledge not to deploy more missiles or nuclear weapons near Russia, and the other is transparency -- i.e. a better heads up on planned military exercises.

Read more: Why Russia-Ukraine Tensions Are So Hard to Defuse: QuickTake

Putin regularly raises what he describes as the risk the U.S. will park nuclear weapons closer to his borders, even as he’s boasted that Russia possesses a new generation of hypersonic missiles capable of evading NATO defenses. U.S. and NATO officials have repeatedly said they view the alliance as defensive in nature.

His rhetoric has increased since 2019, when the U.S. pulled out of a Cold War-era pact with Russia that barred the deployment of ground-based ballistic and cruise missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers -- either nuclear or conventional.

The Trump White House cited what it called long-time violations by Russia for the withdrawal.

Several current and former U.S. and European officials familiar with America’s strategy for the talks acknowledge it’s fraught with risk and may not work. But, according to those officials, the two sides are so badly at odds over Ukraine, with so little chance of resolving that issue anytime soon, that they need to look elsewhere for potential progress or at least to buy time.

Either way, the Geneva talks will set the tone for the broader meetings that follow. Alongside the bilateral U.S.-Russia discussions -- seen by Moscow as the most important -- there will be a meeting of the NATO-Russia council in Brussels next week, then a conversation in Vienna within the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe framework.

The current U.S. assessment is that Russia would need about 10 days to complete preparations for an invasion, should Putin decide to act. That has officials looking at a window from mid-January to the end of February as a potential crunch time.

According to a Ukrainian military map compiled around the New Year and seen by Bloomberg News, Russia now has 52 battalion tactical groups in close proximity to Ukraine. Russia has also developed capabilities to deploy more units in a short period of time, from one to two weeks, the Ukrainian assessment shows.

The meetings also come against the backdrop of sudden turmoil in another Russian neighbor -- Kazakhstan. Anti-government protests there have set off a violent crackdown, and Russia is among allies sending in troops. Putin will have a strong desire to see things stabilize in the large central Asian economy, a big oil producer, and the chaos there has raised the question of whether it’s the sort of distraction that will defer or alter any Ukraine invasion plan.

Still, Leonid Kalashnikov, chairman of the committee in Russia’s State Duma responsible for relations with other ex-Soviet states, said in an interview he believes Russian forces will only be needed in Kazakhstan for a few weeks.

Alongside the potential areas for discussion, the U.S. delegation is likely to repeat the threats of massive economic punishment if Putin were to push ahead on Ukraine. That would include further financial sanctions and barring gas from flowing through the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia to Germany. That pipeline is not yet in operation as it awaits regulatory approvals in Berlin and Brussels.

The U.S. is also pressing ahead with plans to provide Ukraine with more defensive weaponry and the Biden administration has indicated it’s open to allowing allied nations to sell missiles to Ukraine, according to one of the people familiar with the discussions.

Whether such threats will work is another thing entirely.

“I don’t know why our Western colleagues are trumpeting at all corners about the price that Russia will have to pay if the West doesn’t like something in our behavior,” Ryabkov said in an interview this week. “According to simple logic, threats and ultimatums only consolidate the determination of the opposite side to act in its own way.”

The fact that the Russian proposals are so obviously unacceptable to the U.S., as they’d be an abrogation of core principles on European security, has led some current and former officials to speculate they’re designed to fail.

“With large forces near Ukraine, Moscow could then cite that as another pretext for military action against its neighbor,” Steven Pifer, a former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine and senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said in a recent note, adding that the proposals “raise concern that the Kremlin may want rejection.”

That’s a concern shared by the U.S. and Europe, according to diplomats. The other possibility is that Putin’s just staking out an opening position that he’ll back away from in the event of a final deal.

“So is that trade bait?” Pifer said separately in an interview, referring to Putin’s demands on NATO. “Is that something that the Russians put in this agreement that they could give away as a concession and get to a negotiation on some of the other elements?”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.