Aug 5, 2019

Warren’s Private Equity Plan Has One Fatal Flaw

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- “I create nothing,” declared fictional financier Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie "Wall Street." “I own.” In the movie, Gekko buys an airline, laying off workers who have put their whole lives into the company while stripping its assets. This sort of transaction, sometimes referred to pejoratively as looting, has become emblematic of the private-equity industry -- financiers win, workers lose and productive companies get rendered down for spare parts.

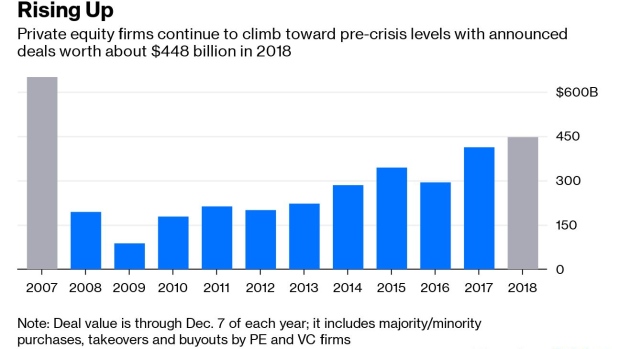

Fast forward to 2019, and private equity has become much more central to the U.S. economy than in the 1980s. As companies increasingly flee public stock markets, getting bought by a PE firm is a natural exit route. For investors, buyout firms are often seen as a way to earn outsized returns -- a 2014 paper by finance researchers Steven Kaplan and Berk Sensoy found that from 1990 through 2012, buyout funds tended to outperform the Standard & Poor's 500 by about 20% during the lifetime of a fund. In 2018, buyout funds raised more than $200 billion from investors.. So-called buyout megafunds, with assets of more than $5 billion, have become more common in recent years. Though PE deal value is still down from its pre-crisis peak, it is on the rise:

The growing importance of private equity has caused consternation among some observers. The first and biggest worry is that PE firms fire too many workers, causing unnecessary disruption to the lives of the economically vulnerable working class. The second is that PE firms load up otherwise healthy companies with too much debt while extracting cash via dividends, consulting fees and other payouts. This can leave profitable companies unable to expand or compete, and set them up to go bankrupt as soon as the next economic shock comes along.

A prominent example of both problems is ShopKo Stores Inc., which filed for bankruptcy in 2018. ShopKo had been acquired by Sun Capital Partners Inc. in 2005 and cited excessive debt as a reason for the bankruptcy, and the company’s employers are demanding compensation from the PE firm.

Furthermore, some suspect that investors are also getting a raw deal from private equity. Legendary financier Warren Buffett recently argued that PE firms charge management fees on capital that they haven’t invested yet, but are advertising rates of return that don’t include this un-deployed capital. Meanwhile, a 2018 paper by a group of accounting researchers contends that after properly adjusting for risk, PE firms don’t really beat the market:

Senator and presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren has a plan to tame the modern-day Gordon Gekkos. Called the Stop Wall Street Looting Act, it would impose a 100% tax on fees paid from companies to the PE firms that buy them, prohibit dividends or other cash extractions for two years after an acquisition, and increase disclosure to investors. It would also make PE firms legally liable for some of the debt of the companies they buy. It would raise tax rates on PE managers’ compensation. And it would allow workers to claim more of a payout in the event that their companies go bankrupt.

The ban on immediate cash extraction is the most sensible piece of this reform (though similar goals could be accomplished simply by taxing cash extraction heavily instead of banning it). Forcing PE firms to become long-term shareholders increases the likelihood that they will focus on improving the operations of the companies they acquire, rather than stripping them of their assets and leaving them to die. Allowing workers to claim some of the proceeds in the event of bankruptcy is also a good reform; it will shift income from capital to labor, and shift risk from workers to investors and financiers.

But as my colleague Aaron Brown notes, making private equity firms and their managers personally liable for the debts of the companies they acquire probably goes too far. Limited liability for shareholders is the foundation of the corporate system; under Warren’s reform, PE-owned companies would essentially become partnerships rather than corporations, while still subject to corporate tax and governance regulations. That would devastate the private-equity industry, and cause a stampede of companies back to the public markets.

That could have negative consequences for the U.S. economy. Although some do engage in asset-stripping, PE firms have also been shown to improve the operational efficiency of the companies they own. This is especially true in Europe. A 2010 paper by economists Quentin Boucly, David Sraer and David Thesmar found that French LBOs tend to lead to higher capital spending, faster growth and higher profits. A 2018 paper by economists Markus Biesinger, Çağatay Bircan and Alexander Ljungqvist found the same result for all of Europe and the Middle East; they also show that PE acquisitions increase productivity, and that these gains are driven by improved operational efficiency. Even in the U.S., there is some evidence that PE firms increase productivity and improve management practices, despite increasing corporate debt (though not all papers find this).

So although the private-equity industry needs to be tamed, it shouldn't be killed. Taxing or prohibiting quick cash extraction, extending protections to workers and raising tax rates on corporate leverage should be sufficient to push the U.S. private-equity industry away from Gekko-style looting and toward the more socially beneficial business of making companies run better.

To contact the author of this story: Noah Smith at nsmith150@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.