May 26, 2022

What Stewart Brand Knew in 1968 About Solving the Climate Crisis

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

In the fall of 1968, Stewart Brand published the first “Whole Earth Catalog.” Aimed at back-to-the-landers and other members of the Sixties counterculture, it was much more than a catalog — a loose compendium of products, reviews, essays and explainers that Brand hoped would enable a reader to “conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested.”

Brand, then a young writer and photographer in California, began the first printing of the first issue with a statement of purpose: “We are as gods and might as well get used to it.”

John Markoff’s new biography of Brand captures a man who is complex and contradictory, both blessed by proximity to key moments and movements and, crucially, able to channel them to great effect. The year 1968 was one of those moments. It is worth exploring because of how it changed environmental thinking, and how environmental thinking, including Brand’s (he is now 83), has changed in the time since.

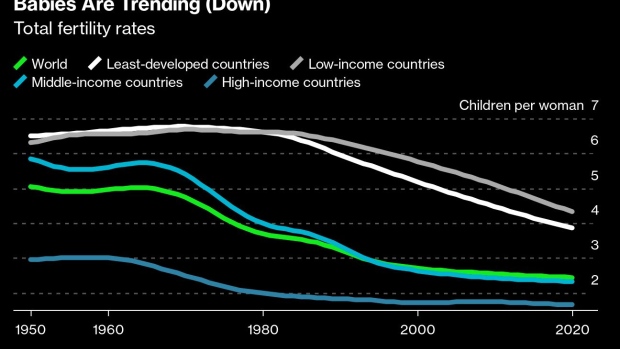

Another defining publication of 1968 was biologist Paul Ehrlich’s “The Population Bomb.” The book baldly stated that in the next decade, “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death.” Nothing could save humanity from the fate of this mass die-off, according to Ehrlich, except a drastic reduction in the human population. As most readers of this newsletter will be aware, neither mass die-offs nor a drastic reduction in the human population occurred in the 1970s. Ehrlich was in fact writing a few years after global birth rates peaked, and very close to their peak in the least developed countries.

That did not prevent “The Population Bomb” from becoming and remaining very influential. Even now, in the US, it informs local objections to building more housing in desirable neighborhoods — often the neighborhoods populated by the sorts who likely read the “Whole Earth Catalog” five decades ago.

But the declining birth rate from the 1960s has an inverse trend: the rising atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide. I find this an unfortunately accurate reflection of Brand’s exhortation that we are “as gods”— engaged in terraforming, essentially. Humans can grow enough food for billions and have extended life spans, but at the same time, we have become quite adept at emitting CO₂ and warming the Earth in the process.

That adeptness makes me reflect on Brand’s tweak to the “Whole Earth Catalog.” The first edition sold so well that it went to a second printing, in which Brand changed his exhortation in a small but important way: “We are as gods and might as well get good at it.”

Climate change is global in cause and in scope. Reducing our collective carbon emissions will require concerted effort everywhere — never mind reducing levels of CO₂ already in the atmosphere, which will require technological fixes and environmental monitoring and verification on a scale never seen before. Doing so will be not so much collective as planetary.

And Brand, several decades after the last “Whole Earth Catalog” shipped in the early 1970s, urged us to become good at things beyond the scale his publication envisioned. In 2005, he wrote an important essay for MIT Technology Review entitled “Environmental Heresies.” In retrospect, not all of these seem quite so heretical. Brand embraced two bugbears of earlier (and some current) environmentalists: genetically modified organisms and nuclear power. Both remain controversial to some, but California, the birthplace of the US anti-nuclear movement, is now hoping to keep its last remaining plant online.

Brand took a nuanced view of his positions. Markoff cites his comments when he declined to accept an award from a US nuclear energy trade group:

To nuclear audiences I talk Green, to Green audiences and the public I talk nuclear (and other things). My identity is with Greens, not with nuclear. That’s how I can be effective and it’s the reality. You can see how an award would confuse that.

To me, Brand’s legacy lies with both his exhortation to “get good at it” and with something even simpler from that very first “Whole Earth Catalog.” The cover features an image of the Earth taken from space, as well as the subtitle “access to tools.” We can read that as another exhortation, in a sense. Get access to the things you need in order to build and change, to the solutions fit for problems at hand. Changing our global emissions trajectory, for example, requires accessing every tool we now have in energy, industry and transportation, at orders of magnitude more scale. It will also require tools that barely exist today.

We must change the trajectory of the climate, or live in a world very different than the one we know. In 2009, speaking to the US State Department, Brand gave us that imperative vision, so to speak: “We are as gods and HAVE to get good at it.” We have access to tools and need more of them; we are capable of changing the planet, so we should learn how to do it well.

Nathaniel Bullard is BloombergNEF’s Chief Content Officer.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.