Oct 20, 2019

When Will Boeing 737 Max Fly Again and More Questions

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Two crashes within five months -- Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018 off the coast of Indonesia and Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 in March outside Addis Ababa -- killed 346 people and led to a global grounding of Boeing Co.’s 737 Max jets, the fourth generation of a venerable brand first flown in 1967. Uncertainty over when it will fly again is rippling through the airline industry and Boeing’s finances. The U.S. manufacturer’s bill is $8.3 billion and rising, as it faces questions about the plane’s development and its own transparency.

1. When will the 737 Max fly again?

Unclear. Boeing says its best estimate is a return to service “that begins early in the fourth quarter,” but airlines including Southwest -- the largest operator of the grounded jet -- American, United and Air Canada have pulled Max flights through early January. The aviation regulator in the United Arab Emirates also raised doubts about Boeing’s timetable, saying he expects the plane to be back in the first quarter of 2020. One question on timing is whether the Federal Aviation Administration will mandate simulator training for pilots before the jet can fly again.

2. Will air travelers get back on board?

At least 20% of U.S. travelers said they would definitely avoid the plane in the first six months after flights resume, according to an April 2019 survey led by consultant Henry Harteveldt. More than 40% said they’d even take pricier or less convenient flights to stay off the Max. UBS Group AG’s most recent survey about the 737 Max found 12% of respondents saying “no amount of safe operation will alleviate their concerns” about flying on the plane. To boost public confidence, American says its executives and other staff will take the first flights, before paying passengers, as soon as the Max is certified fit to fly.

3. What has this meant for the airline industry?

The grounding of the fleet was less disruptive than it might have been because far more jets were in Boeing’s order backlog than in service. In the U.S., for example, the Max makes up about 3% of the mainline fleet. But the impact has piled up and could especially hurt budget carriers. Ryanair Holdings Plc is scaling back growth plans for summer 2020 because, it says, it’s likely to get barely half of the 58 Max planes it was expecting. FlyDubai has idled 14 Max planes that have been delivered out of 251 ordered, according to Boeing. American said it’s canceling about 140 flights a day; at Southwest, that number is 200 on an average weekday. TUI AG, the world’s largest tourism service company, said a profit rebound was wiped out by the grounding of its 15 Max aircraft. The hit to Boeing’s suppliers could be far worse if the company follows through on warnings it might halt production. CFM International, a joint venture between General Electric Co. and Safran SA, cut output by about 5%, while Safran says it may lower its earnings forecast.

4. What has this meant for Boeing?

The Chicago-based company took a $4.9 billion writedown it said would cover potential costs incurred by airline customers due to the grounding; already, Indian budget carrier SpiceJet Ltd. has booked income it expects to receive as compensation from Boeing. In April, Boeing abandoned its financial forecast for 2019 and missed its quarterly earnings estimates for just the second time in five years. (The entire 737 program accounts for almost one-third of Boeing’s operating profit.) On July 7, Saudi Arabia’s Flyadeal became the first airline to officially drop the 737 Max, reversing a commitment to buy as many as 50. Virgin Australia has pushed back delivery of its first 737 Max jets by almost two years. In addition, there’s the prospect of substantial payouts to the families of passengers if Boeing is found responsible for the crashes.

5. What legal action could Boeing face?

Claims have been filed by families of victims in both crashes. Bloomberg Intelligence estimates Boeing’s litigation risks in the U.S. could amount to $1 billion. Boeing has offered $100 million over several years as an “initial outreach” to support the families of victims and others affected, and hired high-profile mediator Kenneth Feinberg to distribute it. On other legal fronts, the U.S. Justice Department expanded its probe to include a look into manufacturing of another Boeing aircraft -- the 787 Dreamliner -- at a new plant in South Carolina. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating whether Boeing properly disclosed issues tied to the 737 Max jetliners to investors. And Boeing faces proposed class action lawsuits by pilots.

6. What does Boeing say?

Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg, who was criticized for a subdued initial response to the tragedies, has apologized for the accidents and said the situation “will continue to weigh heavily on our hearts and on our minds for years to come.” The company has said it thinks the 737 Max will regain its position as the backbone of its single-aisle fleet for many years to come.

7. How many 737 Maxes are out there?

Southwest says it has 34 in its fleet. Other major operators include American (24) and Air Canada (24). Chinese airlines account for about 20% of 737 Max deliveries globally. As of the end of June, Boeing reported 387 deliveries of the single-aisle Max jets to 48 airlines or leasing companies, with orders from around 80 operators for about 4,550 more. Most sales are the Max 8, the model involved in both crashes. (There’s also, from smallest to biggest, a Max 7, 9 and 10.)

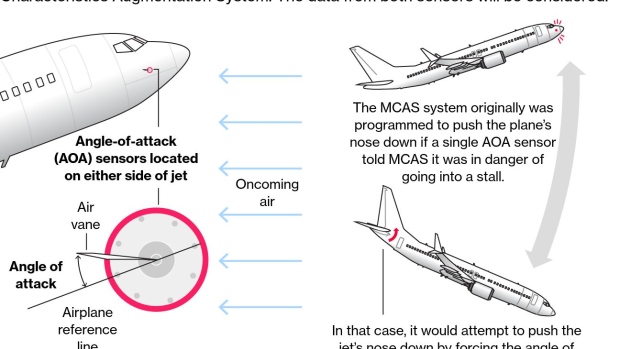

8. What do people think caused the crashes?

In both cases, pilots were likely overwhelmed by a new flight control feature added to the Max known as the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS. The system kicked on due to an erroneous sensor reading and pushed the plane’s nose downward. Pilots commanding the doomed Ethiopian Air jet were hit with a cascade of malfunctions and alarms seconds after taking off from the Ethiopian capital, according to a preliminary report. Indonesia’s preliminary report showed that maintenance and pilot actions were also being reviewed.

9. What’s the purpose of MCAS?

The system activates when the plane appears to be at risk of stalling, a situation in which the wings are losing lift because the jet is climbing too steeply. The use of new, bigger engines on the 737 Max required Boeing’s designers to mount the turbines farther forward on the wings to give them proper ground clearance. That changed the plane’s center of gravity.

10. So what went wrong?

The software had a critical flaw: It relies on the reading from a single sensor called the angle of attack vane, which measures the nose of the plane against onrushing wind. Boeing said there was a simple procedure for shutting off MCAS in case of malfunction. The day before the Lion Air crash, an off-duty pilot on the same aircraft recognized the problem and told the crew how to disable the system, saving the plane.

11. Who approved this system?

The FAA gave final certification to the 737 Max in March 2017, and it entered commercial service two months later. Under a program established in 2005, the FAA had delegated to Boeing the authority to perform some safety-certification work on its behalf. Some FAA employees warned as far back as 2012 that Boeing had too much sway over safety approvals of new aircraft. Boeing said in May that it had known months before the Indonesia crash that the cockpit alert wasn’t working the way it had told buyers, but it didn’t share that with airlines or the FAA until after the Lion Air jet went down.

--With assistance from Alan Levin and Anurag Kotoky.

To contact the reporters on this story: Kyunghee Park in Singapore at kpark3@bloomberg.net;Julie Johnsson in Chicago at jjohnsson@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jon Morgan at jmorgan97@bloomberg.net, ;Anand Krishnamoorthy at anandk@bloomberg.net, Grant Clark, Laurence Arnold

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.