Feb 10, 2024

Why Crypto Stablecoins Still Worry the Fed

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Sometimes a stablecoin is anything but. When Silicon Valley Bank collapsed in March of last year, crypto company Circle Internet Financial Ltd. had $3.3 billion of cash reserves backing its USD Coin parked in the bank and couldn’t get it out. Stablecoins are crypto tokens whose value is typically pegged to a currency such as the US dollar. They offer a way for traders to quickly move between more volatile coins and something approximating cash or a way to hold or send money without using a bank. They can track a normal currency in a variety of ways—chiefly by holding assets such as cash or government bonds to support the value of the coin.

With about 8% of USDC’s reserves stuck in a failing bank, the stablecoin experienced its own panic. Traders raced to get out, dragging its price well below $1 over the dramatic weekend when regulators were figuring out what to do about SVB. After the government stepped in to make all of the bank’s depositors whole, USDC’s price recovered. “Following last year’s banking crisis, Circle upgraded the market infrastructure behind USDC to be the strongest, safest, most transparent digital dollar on the internet today,” a Circle spokesperson says.

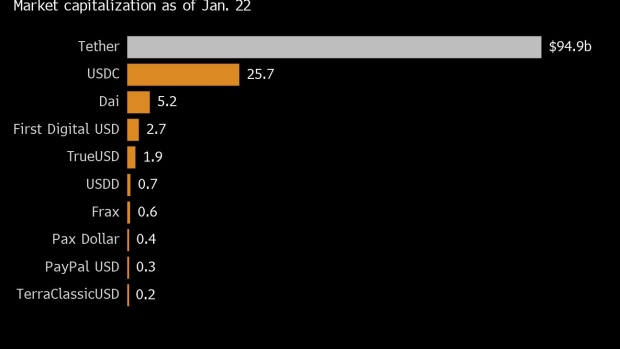

The crisis showed how stablecoins can be buffeted by troubles in the traditional financial world. But some worry that stablecoins, with a total market value of $136 billion as of late January, could have the potential to rock real-world markets in return. “They are becoming more interconnected, more interlinked with the traditional financial system,” says Hilary Allen, a law professor at American University Washington College of Law.

That interconnectedness continues as the crypto mania that peaked in 2022 is returning. BlackRock Inc., the world’s biggest asset manager, now manages USDC reserves. Bank of New York Mellon Corp. custodies them. Circle filed for an initial public offering in January. Cantor Fitzgerald LP oversees “ many, many” of the assets of the largest stablecoin, Tether, says Chief Executive Officer Howard Lutnick. Mastercard Inc. and MoneyGram International Inc. enable stablecoin payments. PayPal Holdings Inc. introduced its own stablecoin in August. And JPMorgan Chase & Co.—notwithstanding CEO Jamie Dimon’s crypto skepticism—is exploring a stablecoin-like product for moving deposits.

One reason for the interest: Stablecoins and similar products that use blockchain ledgers can allow issuers to enter new areas, such as cross-border payments and trade settlement. Another: There’s money on the table. Thanks to the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes, stablecoin issuers can collect yields of more than 4% by investing in US Treasuries and other traditional financial instruments. Tether alone had direct or indirect exposure to $80.3 billion in US Treasury bills at the end of the fourth quarter, according to its website.

Such investments are making regulators nervous. In a September paper, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York compared stablecoins to money-market funds—noting how in 2008 investors fled funds with larger exposures to Lehman Brothers and asset-backed commercial paper. “Should stablecoins continue to grow and become more interconnected with key financial markets, such as short-term funding markets, they could become a source of financial instability for the broader financial system,” the paper says.

Runs on various stablecoins have happened multiple times already. One important risk is that such a rush for the exits could harm markets for the assets that back stablecoins. There’s also the danger that, over time, crypto tokens could change the very structure of the financial system. Stablecoins might start cannibalizing bank deposits, an important source of cheap funding for lenders, says Austin Campbell, an adjunct assistant professor specializing in crypto and finance at Columbia Business School. “The true risk is unbundling payments from lending,” he says.

Along the way, crypto tokens could also erode consumer protections. “Stablecoins purport to have convertibility one-for-one with the dollar but in practice have been less secure, less stable and less regulated than traditional forms of money,” Federal Reserve Governor Michelle Bowman said in an Oct. 17 speech at Harvard University.

When it comes to transparency, stablecoin issuers are often seen as lacking—especially the biggest player. The US Commodities Futures Trading Commission fined Tether in 2021 after finding its claims of being fully backed by US dollars were untrue. Tether agreed to pay without admitting or denying the allegations. Cantor Fitzgerald CEO Lutnick says his firm has reviewed Tether’s assets. “They have the money they say they have,” he said in a January interview on Bloomberg Television. The British Virgin Islands-incorporated company hasn’t provided a formal, independent audit of how it backs its coin.

There are also questions about regulation, even when issuers have licenses or charters to be custodians of assets or to transmit money. “While many of these issuers are subject to state supervision, they are not subject to the full complement of prudential regulation applicable to banks like capital requirements and prudential supervision,” Bowman said in her speech. She suggested stablecoins should be subject to the same regulations as banks.

Treating stablecoins like banks could also mean providing safety nets such as deposit insurance and Fed liquidity backstops. Law professor Allen worries this would only bring everyday finance closer to the casino-like world of crypto trading, which is currently the main use for stablecoins. Although stablecoins also share some similarities with money-market funds, the industry has resisted the idea that the tokens should be regulated as securities.

Stablecoin legislation is stuck in Congress, and federal agencies are butting heads over how to regulate the industry. Amid regulatory uncertainty, enforcement against stablecoin providers has ramped up. In early 2023, US-based issuer Paxos received a notice from the US Securities and Exchange Commission that it intended to sue the company over selling an unregistered security, the Binance-branded BUSD stablecoin. Paxos contended that BUSD is not a security and issued a statement saying it disagreed with the SEC. The regulator has not filed suit. Paxos stopped issuing new BUSD after an order from the New York Department of Financial Services.

Around the same time, the SEC charged Terraform Labs, the issuer of the collapsed TerraUSD stablecoin, with defrauding investors. Founder Do Kwon also faces criminal charges. That coin worked differently than fiat-backed coins—it was linked to the value of another crypto coin called Luna and drew investors to apps with unsustainable 20% yields. Its unraveling wiped out billions of dollars and helped kick off the crypto meltdown that exposed the fraud at the FTX exchange.

With some crypto-native entities struggling, giants of traditional finance have jumped into the fray, thinking they can fill a gap and meet regulators halfway. “All the big players in the market are trying to position themselves: ‘How can we be the biggest stablecoin player of all?’ ” says Seamus Rocca, CEO of Xapo Bank in Gibraltar. “ ‘Because why would we give that business to Tether?’ That’s what’s going on.”

Many of the traditional companies say they’re afraid to miss out on an innovation. Alex Holmes, CEO of MoneyGram, likens stablecoins to Napster. Sharing digital files opened the way for online music and streaming services. “It didn’t take long for Apple and others to figure it out. It takes off incredibly quickly,” Holmes says. Similarly, a token of value that users are willing to exchange into a local currency can be a solution for payments, he says. “The net is, it’s a technology. If you are a company like MoneyGram, like Visa, like Mastercard—that’s where you can begin to push the envelope.”

Payments giant PayPal worked with Paxos to issue its stablecoin, which it offers on its app and website. The token had a $301 million total market value as of Jan. 22, according to CoinGecko, a crypto data site. “PayPal just recognized that a stablecoin could be very transformative to their business,” says Charles Cascarilla, CEO of Paxos. “They worked very hard to be able to get this out to their customers.”

MoneyGram’s stablecoin-based money-sending service runs on a smaller blockchain called Stellar. Since not many people have Stellar wallets, its usage is likely low. Others are involved in trials mostly outside the US. Mastercard in June announced a test version of its Multi Token Network in the UK. The network is testing use cases based on deposit tokens—stablecoin-like tokens backed by bank deposits. Potential applications include trade finance, real estate and cross-border payments, according to the company. “We are working toward making some of these use cases live in the UK,” says Raj Dhamodharan, an executive vice president at Mastercard.

In the US, JPMorgan is in the early stages of exploring deposit tokens for cross-border payments and settlement. Its idea is that such tokens can fit into traditional banking practices and fully comply with current laws. A JPMorgan paper contends that deposit tokens will eventually become “a widely used form of money within the digital asset ecosystem, just as commercial bank money in the form of bank deposits makes up over 90% of circulating money today.” Mastercard is working on several pilots of another stablecoin-like instrument—central bank digital currencies, which are essentially tokens issued by central banks—in places including Hong Kong and Australia. Even the tame CBDC version is giving the Fed pause, though. “If not properly designed, a CBDC could disrupt the banking system and lead to disintermediation,” Bowman said in her Harvard speech.

Noncrypto financial companies are more focused on keeping a toe in the tech, if only to make sure they aren’t left out in the event it takes off. “We are not here to pick winners and what is the right currency format,” says Dhamodharan. “Our role is to make sure we support all eligible currency formats and let the market decide where it goes.”

Kharif and Yang cover cryptocurrencies for Bloomberg News. Kharif is in Portland, Oregon, and Yang is in New York.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.