Jan 29, 2021

Why Enough Hong Kongers to Fill Belfast May Flee to the U.K.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- When the U.K. starts accepting special visa applications from Hong Kong residents on Sunday, Chen will be among the first in line. The 40-year-old former Airbnb host believes time is running out as local officials urge action to discourage people from relocating to their former colonial homeland.

“If we don’t leave now, we many never be able to leave again,” Chen, who asked not to be identified by his full name due to fear of reprisal by the government, said in an interview Thursday. He and his wife plan to leave immediately and hope to settle in Brighton, because, “like Hong Kong, it’s near the sea.”

The U.K. expects some 322,000 Hong Kong residents who hold special passports created before the city’s return to Chinese rule in 1997 to take advantage of the new pathway to citizenship over the next five years. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government announced the visa program for British National (Overseas) passport holders in July, after accusing Beijing of violating the terms of Hong Kong’s handover by enacting a strict national security law.

Such an exodus -- equal to roughly 4% of Hong Kong’s population -- could have a profound impact on both Hong Kong and the U.K., fresh from its break with the European Union. The departure could result in a capital outflow of HK$280 billion ($36 billion), according to a Bank of America report published earlier this month. The projected number of immigrants would be almost as large as the population of Belfast.

“We have honored our profound ties of history and friendship with the people of Hong Kong, and we have stood up for freedom and autonomy -- values both the U.K. and Hong Kong hold dear,” Johnson said in a statement Friday. The plan allows for BN(O) holders to settle and apply for full citizenship after five years, provided they can meet stringent health and financial requirements in the initial application.

The geopolitical implications could also be significant, as it represents the most tangible protest yet against Chinese President Xi Jinping’s campaign to curb dissent in the restive Asian financial center. China has denounced the program as a breach of Thatcher-era promises against mass citizenship for Hong Kong residents, and some pro-Beijing officials have called for banning BN(O) holders from public office, or stripping their Chinese nationality -- potentially leaving them stateless.

“The Chinese side has repeatedly expressed its grave concern and strong opposition and will certainly respond with countermeasures,” the Chinese Embassy in London said in a statement Friday. The Chinese Foreign Ministry separately said it wouldn’t recognize the passports as travel documents, a move that would have little practical impact since Hong Kong residents usually travel into and out of the city using their local identity cards.

While Hong Kong has endured several waves of migration since the U.K. secured the trading post during the Opium Wars 180 years ago, the population has continued to swell to 7.5 million. Millions of Chinese flooded into the city in the decades after the Communist Party took power in 1949 and some emigrated after the Tiananmen Square crackdown fueled anxiety about the handover. In the years since, more than a million mainland Chinese have moved in.

As many as 5.2 million people are potentially eligible for the BN(O) visa, a figure equivalent to more than two-thirds of Hong Kong’s population.

“This time, many feel that there is no home to go back to,” said Victoria Hui, an associate professor at the University of Notre Dame specializing in Hong Kong politics. “So far, Beijing seems OK to have a ‘blood transfusion’ by bringing in mainland funds and mainlanders to fill the void. Beijing won’t mind Hong Kong people leaving, so long as the city itself continues to enjoy all the benefits of an international financial center.”

Hong Kong has played down the threat, with top government adviser Bernard Chan predicting it would be “far, far smaller” than forecast and that those who do leave will either return or be replaced by mainlanders. The city’s Beijing-backed leader, Carrie Lam, attempted Thursday to recast the Beijing-drafted national security law as a reason to stay. She questioned whether residents would want to give up local health care for the U.K.’s pandemic-strained National Health Service.

‘What If I am Arrested?’

“The important thing is for us to tell the people of Hong Kong that Hong Kong’s future is bright, business prospects are good,” Lam said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “The worries about street violence and social unrest and intimidation have subsided very significantly.”

The security legislation, which Xi’s government imposed on Hong Kong in June without public debate, was chief among the concerns of likely applicants interviewed by Bloomberg. Some with children said they were particularly worried about political pressure in the schools, with the government vowing to “cut off” the “black hands” in the education system and revoking teachers’ certifications for discussing subjects like Hong Kong independence in class.

“What if I am arrested for saying something against the government while teaching, or even a simple chat with colleagues?” said Wong, a 34-year-old education administrator and part-time English teacher who’s planning to leave. One WhatsApp group focused on helping educators get skills and certifications to secure employment in the U.K. has more than 100 members.

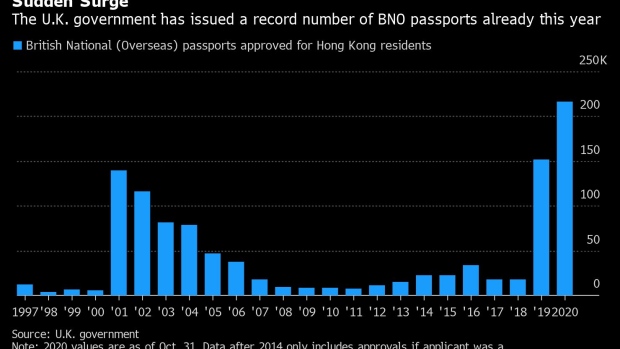

Passport Applications Surge

Concerns about finding a job and providing the required proof of financial support, as well as apprehension of about the U.K.’s Covid-19 situation, could cause some to balk at the visa. Still, political concerns were overriding some of those worries. Almost 44% of Hong Kongers would emigrate if they had the chance, according to a Chinese University of Hong Kong survey published in September, and threats to punish BN(O) passport holders provide another motivation to act quickly.

Lam’s predecessor, former Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying, has advocated stripping BN(O) holders of their Chinese nationality. Lawmakers in Beijing are also discussing whether to ban BN(O) holders from public office, the South China Morning Post newspaper reported earlier this month.

Passports applications surged after the security law’s passage. Some 7,000 Hong Kong residents with BN(O) status and their dependents secured U.K. permission to stay between July and January, the U.K. said.

Wong, who would be moving on his own, said he is still struggling with the idea that he might not see his parents any time soon.

“This time once I leave, I will leave forever,” Wong said. “So that is a very big decision.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.