Dec 21, 2023

A Law to Help Neglected Diseases is Giving Billion-Dollar Drugs Government Freebies

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc. has made over $20 billion in worldwide sales from a cystic fibrosis drug approved four years ago that can cost up to $300,000 a year.

With blockbuster sales like that, Vertex wouldn’t appear to need government assistance. But thanks to an obscure program designed to incentivize companies to make drugs for uncommon or neglected diseases, the Food and Drug Administration also awarded Vertex a bonus certificate that it can either use to expedite a future drug approval or sell for around $100 million.

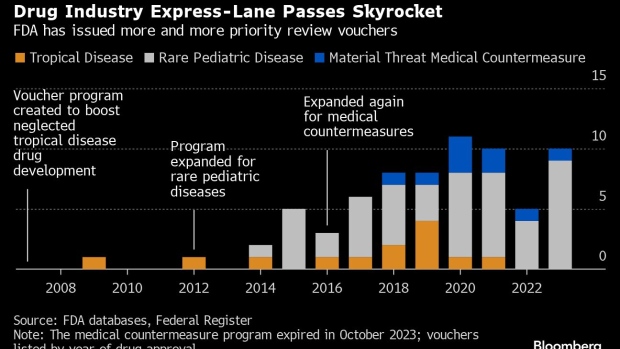

Congress introduced these incentives, known as priority review vouchers, in 2007 to reward companies for developing treatments for tropical ailments like malaria and cholera. The program was later expanded to include rare pediatric disorders, emerging infectious diseases and bioterror threats. Each voucher can be used to cut months off of an FDA review of a future product. The government also gave companies the ability to sell their vouchers, largely to help those making drugs for neglected diseases since they don’t typically make a lot of money.

The program has exploded in recent years and vouchers are being granted for blockbuster drugs that would have been developed anyway, according to an analysis by Bloomberg News. The flood of vouchers has made them less lucrative for would-be sellers like small companies and nonprofits that need the cash to keep pursuing rare diseases. Meanwhile, Big Pharma benefits. Eli Lilly & Co.’s popular diabetes drug Mounjaro came to market in 2022 — roughly four months faster than it normally would have — using a voucher. Lilly doesn’t have to disclose information about the voucher it used, but it appears to be one the company purchased for $80 million in 2018. Mounjaro, which exploded in popularity due to its use in weight loss, has already surpassed $1 billion in quarterly sales.

“Those that need it least win most,” says Els Torreele, a health policy researcher at University College London.

The drug industry has used a variety of FDA-sanctioned shortcuts to get drugs onto the market faster. One particularly controversial program allows drugs to be approved without proof that the medicines even slow a disease, Bloomberg’s reporting has shown. More than two dozen drugs that were rushed to market based on preliminary data were delayed or behind schedule in completing confirmatory trials as of earlier this year. In one extreme example, the FDA has allowed a $900,000-a-year cancer drug to remain on the market for 14 years without evidence that it works.

In the case of priority review vouchers, Bloomberg’s analysis found the FDA granted them to at least 8 drugs that wound up earning $1 billion or more in annual global sales — what's known in the industry as reaching blockbuster status.

Awarding a voucher to a drug with potential to bring in more than $1 billion in sales “is laughable,” says Harvard Medical School researcher Aaron Kesselheim. “It is not how the program was intended to work.”

At least 70 priority review vouchers have been granted since the program began, including 10 for drugs approved so far this year, Bloomberg found. Two-thirds were for rare pediatric diseases, which can be blockbuster drugs for pharma companies anyhow. Neglected tropical diseases made up 19% of vouchers, and infectious diseases and bioterror threats – things like anthrax antidotes – accounted for just 13%. (The law authorizing vouchers for the bioterror threat category recently expired, and the FDA isn’t issuing them anymore.)

Studies by Kesselheim and colleagues found the existence of the voucher program hasn’t actually increased the number of new drugs entering human trials for neglected tropical diseases and rare pediatric conditions. The rate has remained constant before and after the law was enacted.

Nancy Goodman, a lawyer who lost her 10-year-son to a rare brain tumor in 2009, was a driving force behind extending the law to pediatric diseases. She says it’s helping stimulate research into rare childhood cancers, even though some undeserving companies end up getting vouchers.

“Did we draw the line exactly right? No. Is it possible to? I don't think so," says Goodman, founder of the nonprofit Kids v Cancer.

Companies are always looking for ways to expedite the FDA’s review process, the final step in what’s often a 10- to 15-year battle to reach paying patients. The FDA uses a two-tiered system for new drug applications, and priority review vouchers were designed to give companies an on-ramp to the express lane. That can shave four months off the standard 10-month deliberations. The FDA offers this shortcut for free to drugs that are significant improvements over the standard of care, but a voucher guarantees a spot in the fast lane for drugs that aren’t big medical advances and wouldn’t otherwise qualify. Notably, it doesn’t guarantee a medicine will be approved, just reviewed more quickly.

Like carbon credits, vouchers can be bought and sold and the value fluctuates. In a 2006 study proposing the program, Duke University economist David Ridley and his colleagues estimated that FDA vouchers might sell for $300 million, providing a large incentive to tiny companies working on drugs for neglected diseases. Early on, one voucher was sold to Abbvie Inc. for $350 million. But prices dropped sharply as vouchers flooded the market. Recent sales have been around $100 million.

Ridley defended the concept and pointed to new treatments for tuberculosis and river blindness that resulted from the program. But he thinks the criteria for getting vouchers has gotten too loose. “With fewer vouchers, the incentive would be stronger and would motivate more tropical disease product development,” he says.

Companies aren’t required to disclose when they buy or sell a voucher, or how much they paid. At least 24 vouchers have been redeemed through the end of 2022, Bloomberg’s analysis found, meaning most vouchers appear to have gone unused so far.

When big companies are issued a voucher, they might sit on it for years until they have the right drug to speed to market, Ridley says. Selling it immediately might signal to investors that they have nothing in their pipeline that’s worth expediting.

In 2020, Novo Nordisk A/S said it planned to use a voucher to accelerate its obesity drug Wegovy to US pharmacies. Lilly took notice and at one point planned to use a voucher this year on Zepbound, its much-hyped competitor for weight loss, but the FDA wound up giving the drug free priority review.

Lawmakers in both parties like the voucher system because it’s a way for them to support research into important diseases without spending any taxpayer dollars up front.

But the law governing it has holes. As a result, the program has disproportionately benefited some companies that were already focused on rare diseases before the voucher program was expanded to include those conditions, the Bloomberg analysis found.

In the case of Vertex, a company with a market value around $100 billion, its scientists were working on cystic fibrosis for years before rare pediatric disease vouchers existed. The company has since received three vouchers, two for cystic fibrosis drugs and one for a pioneering sickle cell gene-editing therapy that was just approved with a cost of $2.2 million per treatment. Vertex declined to respond to questions about its use of vouchers.

Sarepta Therapeutics Inc., which sells several muscular dystrophy drugs, has been awarded four vouchers, tied with Novartis for the most of any one company. Sarepta made $437 million by selling all of its vouchers and has invested the proceeds into developing new medicines, according to a spokesperson. Novartis confirmed that it received four vouchers for a variety of drugs including a medicine for malaria, but declined to comment further.

Biomarin Pharmaceutical Inc., which specializes in rare genetic diseases, sold all three of its vouchers for an undisclosed amount. The company said it invested the proceeds in developing future drugs where there’s significant unmet medical need. In 2021, Sanofi shared a voucher with the nonprofit Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative for a new treatment for sleeping sickness, a parasitic disease common in some parts of rural Africa.

One of the clearest voucher success stories is a drug for river blindness called moxidectin, which was made by Medicines Development for Global Health. The Australian nonprofit was able to raise the $13 million it needed for final studies by telling investors they would recoup the money after approval and sale of the accompanying voucher. The voucher was later sold to Novo Nordisk for an undisclosed amount.

But moxidectin only needed modest funding to cross the finish line. Medicines Development for Global Health estimates it needs to raise $50 million more to bring its next product to the market, a drug for complications of leprosy. Its investors are reluctant to foot the bill this time with voucher prices declining, so the company says it’s been forced to scrounge for grants instead.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.