Jan 21, 2022

Biggest threat to global economy in 2022? Inflation, not Omicron

, Bloomberg News

Expect tightening for the next couple of years: Strategist

News flash: The coronavirus isn’t going to be public enemy No. 1 for the global economy in 2022. The biggest dangers this year will stem from inflation and the risk that policymakers will call the post-COVID recovery wrong.

This is the year we’ll find out whether the global economy is robust enough to get by with less help from governments and central banks. And whether inflation is a temporary byproduct of COVID or a more persistent problem.

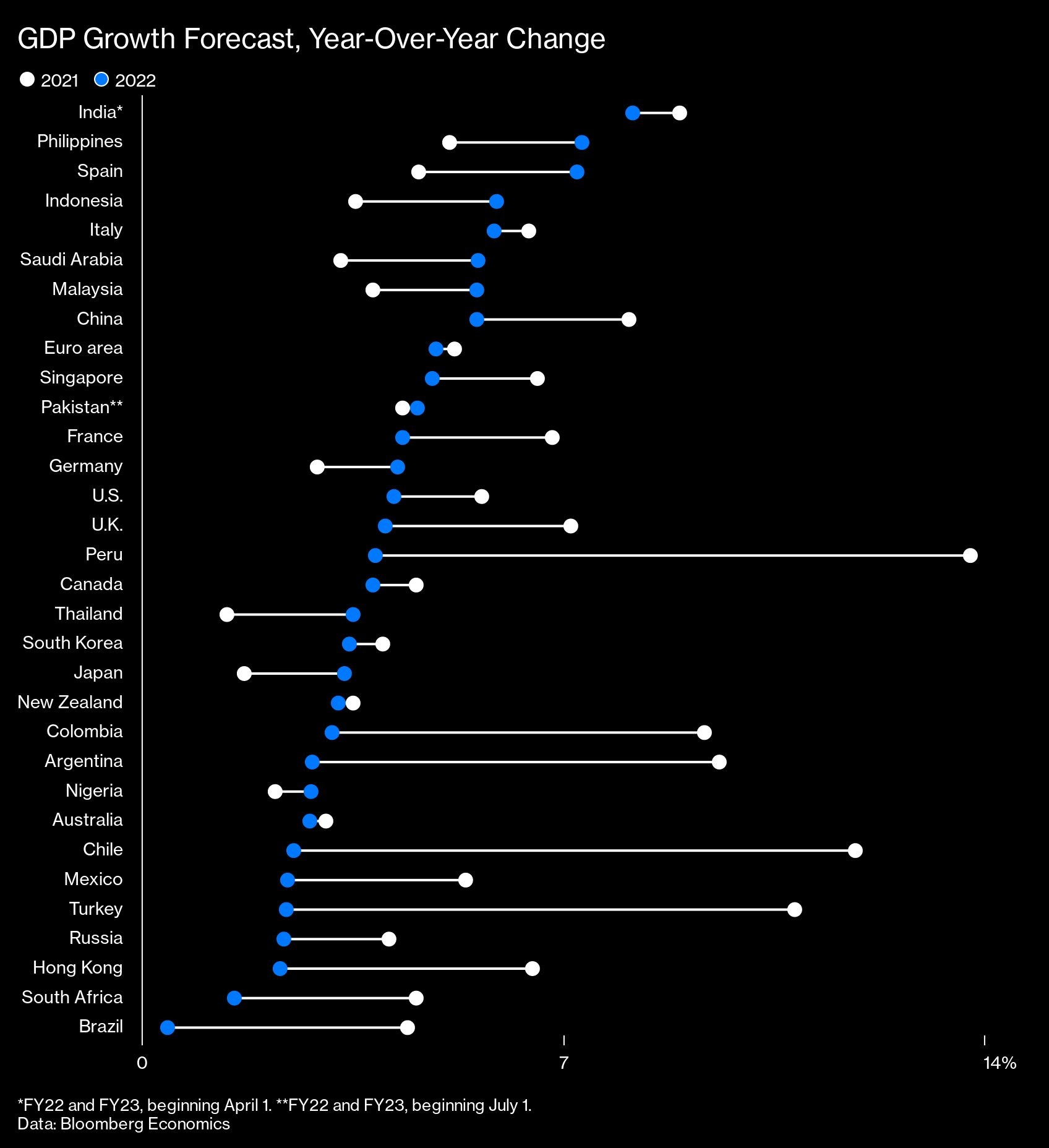

When confronted with a wide range of possibilities, forecasters usually settle somewhere in the middle. Among those Bloomberg surveyed, the consensus is that the world economy will expand 4.4 per cent in 2022, after the 5.8 per cent bounceback of 2021. From 2023 onward, most agree, growth will return to its long-term norm of around 3.5 per cent, as if COVID never happened.

There’s just one problem. From ground level, nothing about this economy looks normal; it’s completely out of whack. If that’s still true in 12 months, policymakers will almost certainly have messed up.

Take the labor market. There were at least 10 million job vacancies across the U.S. at the end of 2021, which every restaurant manager, plant foreman, and chief executive will tell you they’re struggling to fill. The labor shortage shows up everywhere—except in the statistics. Dig into the numbers, and you’ll find at least 5 million adult Americans not working today who were gainfully employed at the start of 2020.

The U.S. isn’t the only country with workers missing in action. The U.K. had more than a million unfilled jobs in November but at least 600,000 more people sitting on the sidelines of the job market than at the start of 2020. They are declining to take up work even as wages pick up.

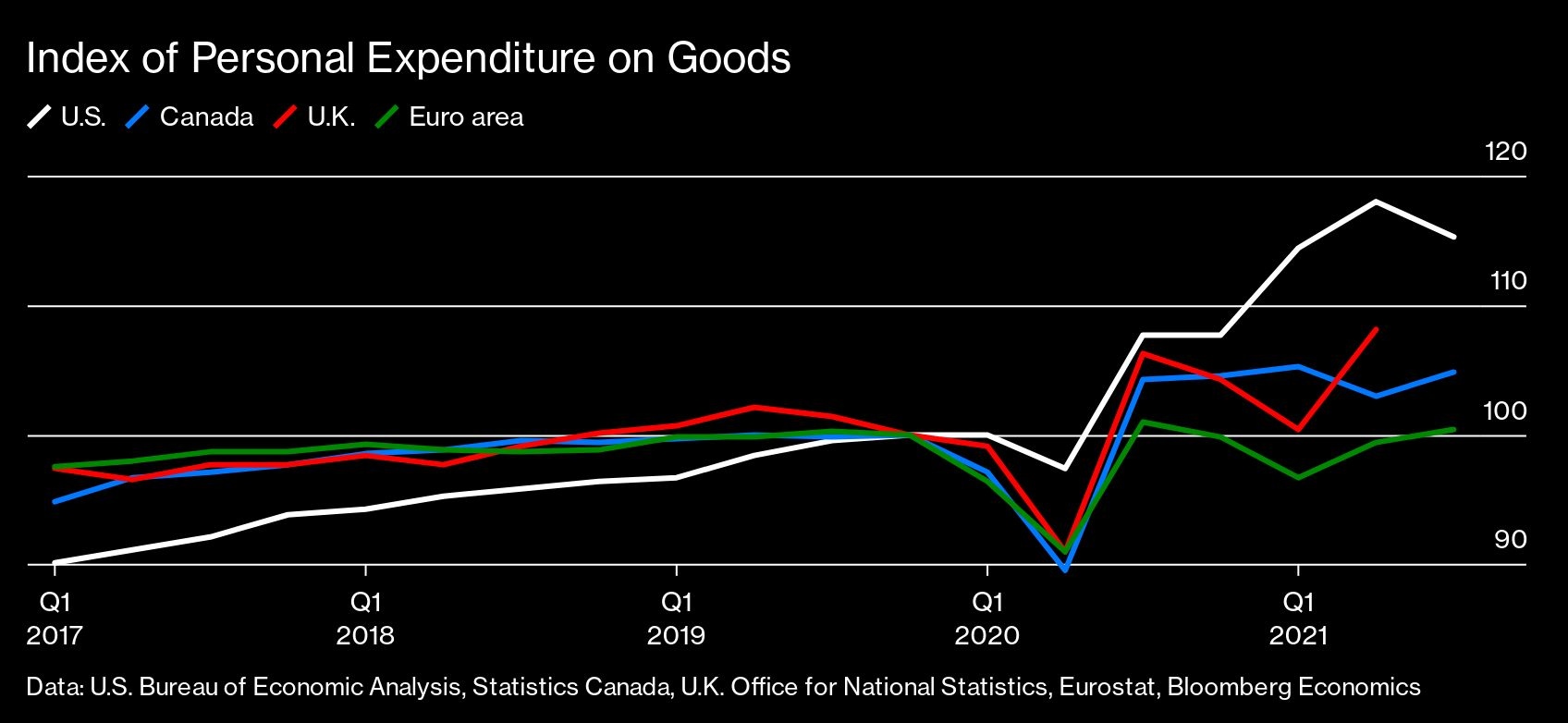

Whether it’s waiters or truck drivers, microchips or cream cheese, the mismatch between demand and supply has become the leitmotif of the COVID recovery—the legacy of a crazy 18-month period that saw the world’s biggest economy shrink by almost 20 per cent in six months then gain it all back by the middle of 2021.

The big winners from that historic bounce were U.S. households, whose wealth soared thanks to booming real estate and stock markets (that is, those that had wealth to begin with). Collectively, Americans had an estimated US$2.6 trillion in extra savings sitting in their bank accounts as of midyear, a stash that equals 12 per cent of gross domestic product.

For much of 2021, policymakers at the Federal Reserve and many other central banks felt confident dismissing the labor shortages and supply-chain bottlenecks as short-term consequences of the pandemic. Lingering fear of COVID and those extra federal dollars in bank accounts were discouraging many of the unemployed from returning to work. Give it time, and these issues will get sorted out, the central banks reasoned.

That a good portion of the 2021 inflation “surprise” was due to rising energy prices appeared to strengthen the case for central bank inaction, because higher fuel costs, on balance, tend to slow growth. But by Thanksgiving, U.S. consumer price inflation was running at 6.8 per cent a year, the highest since Ronald Reagan was president and about three times the Fed’s forecast at the start of 2021.

So in December the narrative finally shifted from “It’s transitory” to “It’s taking so long to move on, it may need a kick,” and markets are now betting the Fed will hike interest rates at least three times in 2022. The Bank of England, expecting inflation to go above 6 per cent in the coming months, got a head start at its last policy meeting of 2021, raising interest rates by 25 basis points. Investors have penciled in another four increases in 2022.

The European Central Bank hasn’t raised its policy rate in more than a decade, and its president, Christine Lagarde, has said an increase isn’t in the cards this year either. The 19-country euro zone is less inflation-prone than the U.K. and the U.S. to start with, plus its economic recovery has been less robust. Nonetheless, with the latest data release showing that consumer prices increased at a record pace of 5 per cent in the year through December, the ECB could also come under pressure to hike.

So we know that the world’s most important central bank will be withdrawing support from the economy, and others may not be far behind. The course of 2022 will be shaped by whether that’s too much for the recovery to take or whether it’s too little, too late.

It used to be that central banks caused most recessions. To be on the “too much” side of the argument and worry about the Fed causing the next one, it helps to be pessimistic about the economic fallout from the omicron variant and also to fear the economic side effects of federal stimulus dollars drying up at the same time interest rates are rising.

Bloomberg Economics expects that omicron will have a visible but short-lived effect on growth. Each successive peak in infections has tended to have diminishing economic costs, in part because everyone has gotten better at handling the economic fallout. Omicron appears to be more contagious but less deadly than earlier variants. Spikes in infections could still weigh on economic activity in the short term by pushing absenteeism sharply higher—as is already happening in the U.S. and U.K. Yet in the longer term, omicron’s arrival could speed the transition from pandemic to endemic, reducing the need for economically disruptive lockdowns.

The hit from governments ending support spending is harder to play down, because it’s simple arithmetic. The U.S. economy had two years and a trillion dollars in federal stimulus, much of it in the form of cash handouts. Removing all of that inevitably punches a hole in total demand worth at least 3 per cent of GDP, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. chief political economist Alec Phillips. And that forecast assumes that the Biden administration manages to pass its US$1.75 trillion Build Back Better plan, which is spread over 10 years and might add 0.5 percentage point to growth in 2022. All or most of that extra spending could evaporate if the White House cannot cut a deal with West Virginia’s Democratic Senator, Joe Manchin, who’s a holdout.

Will this about-face for both fiscal and monetary policy kill the global recovery? Financial markets don’t seem to think so. Global equity markets were worth about US$150 trillion at the end of 2021, having doubled in value since March 2020. The broad S&P 500 index of U.S. stocks even managed to go up on the day the Fed announced it would be tapering off its bond purchases faster to clear the runway for rate liftoff.

Bloomberg Economics expects the U.S. economy to grow at a 4.4 per cent pace through the first half of 2022, despite the hit to spending and investment from omicron and the withdrawal of federal stimulus, slowing to a still respectable 2.7 per cent in the second half. One big reason: The majority of American consumers still have money to spend—that extra US$2.6 trillion sitting in bank accounts. And, for once, that money isn’t concentrated among the richest households, probably because an estimated two-thirds came from government handouts.

Anna Wong, chief U.S. economist at Bloomberg Economics, reckons that a family with income in the US$24,000 to US$75,000 range now has enough of a cushion to maintain pre-pandemic spending for at least another two months without cutting into regular savings. This group would typically have little or no financial wiggle room at all.

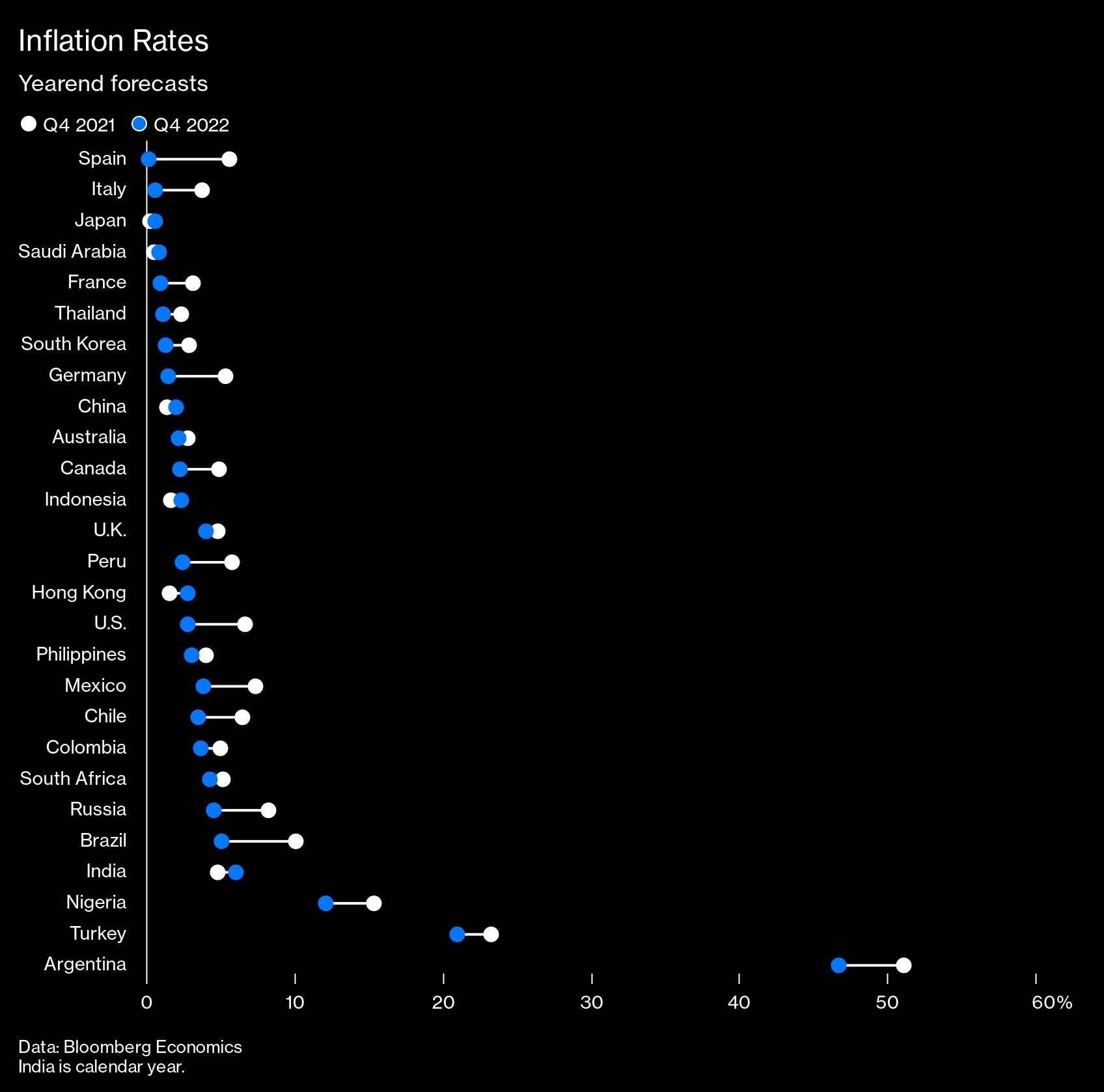

Assume the U.S. economy can withstand monetary tightening. What about the rest of the world? Shifts in the Fed’s stance may spur a flight of money to the U.S. and away from riskier markets. Many emerging-market economies will face a difficult choice between raising rates themselves to stem outflows or keeping them low to sustain the domestic recovery. Ziad Daoud of Bloomberg Economics has identified five that are especially vulnerable to rising U.S. rates: Brazil, Egypt, Argentina, South Africa, and Turkey, or the Beasts. (Although President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s unconventional approach to taming inflation, by cutting rates, arguably puts Turkey in a class of its own.)

Overall, emerging-market policy rates will probably go up, but Bloomberg Economics anticipates that these economies, excluding China, will grow 4.8 per cent in 2022. That’s almost 2 percentage points lower than in 2021, though it’s well above pre-COVID levels.

The biggest reason the world might be able to shrug off the impact of Fed tightening is that the ECB and the Bank of Japan are committed to keeping rates at rock bottom for the time being. So there’s still a lot of cheap money floating around the world in search of a home. This partly explains why long-term interest rates—as reflected in the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds—haven’t reacted very dramatically to the Fed’s plans to raise short-term rates.

Another is that the People’s Bank of China, for the first time in living memory, is going to be moving in exactly the opposite direction from the Fed. This is a big deal, the monetary analogue to China’s top diplomat, Yang Jiechi, telling U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken where he could put his lectures about human rights at their fractious first meeting in Alaska in March. By loosening policy to support an economy struggling with the effects of a property market crackdown at the same time the Fed is tightening, the PBOC will be making its own declaration of independence from the U.S.

For Europe the wild cards this year will be energy costs and politics. Gas and electricity prices are at record highs because of nuclear shutdowns in France and reduced supplies of Russian natural gas. Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi has argued that governments need to take action to protect consumers, but governments already carrying a lot of extra debt won’t relish having to help out again.

In France the energy crisis and a potential sixth wave of COVID will provide the backdrop for a presidential election that, barring a last-minute upset, will likely see Emmanuel Macron hold on to power.

Italy’s future looks less certain following the surprise news in December that Draghi may seek the presidency, leaving the more hands-on job of prime minister to someone else. Voting begins on Jan. 24. Italy is still deemed the country most likely to cause the next European financial crisis, and none of Draghi’s likely successors have the stature of the former ECB president nor the confidence of other European leaders and international investors.

In the U.K., after a string of political scandals, many now expect Prime Minister Boris Johnson to be ousted in a party coup sometime in the first half of 2022. Mujtaba Rahman, managing director for Europe at the Eurasia Group Ltd., a political-risk consulting company, puts a 40 per cent probability on Johnson losing power by the end of the year. But with no parliamentary election on the horizon, a change of leadership will possibly not have a big impact on the handling of the economy.

Let’s shift our attention back to the U.S., which for better or worse dominates any discussion about the trajectory of the global recovery, because it generates approximately one-quarter of world output. Investors are pricing in only three U.S. rate increases in 2022. Bloomberg Economics sees the Fed’s latest forecasts for the unemployment rate and core inflation as consistent with six hikes. But even that would barely take the main U.S. policy rate above 1 per cent by yearend, well below inflation and below the pre-COVID level.

With or without President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better spending, it would be surprising if those hikes were enough to stall an economy that entered the year with significant momentum. The bigger question, then, isn’t whether Fed Chair Jerome Powell and company will have done too much by the end of the year but rather will they have done enough?

“My fear is that we are already reaching a point where it will be challenging to reduce inflation without giving rise to recession,” said former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers in an interview in December. The economist and Bloomberg contributor worried early and often in 2021 that President Biden’s US$1.9 trillion COVID-relief package would stoke inflation without doing much to increase underlying growth. His argument, that a third round of short-term stimulus wasn’t really needed, looks stronger now that we have household data suggesting U.S. families had collectively already made up all of the pandemic shortfall in wage income by the time the package was passed in the spring.

Plenty of others have joined Summers in the peanut gallery taking shots at the Fed, among them economist and Bloomberg columnist Mohamed El-Erian, who rates the Fed’s “transitory” line on inflation “probably the worst inflation call in the history of the Federal Reserve.”

To believe it’s going to take more than a few interest-rate increases to kill inflation, it helps to have the view that supply side problems are only partly to blame for higher prices. Also, that workers in this out-of-kilter COVID economy suddenly have leverage to extract increasingly hefty wage rises from employers. U.S. hourly wages rose 5.8 per cent in October from the previous year, the third-highest year-over-year wage growth since the early 1980s. A broader measure of wages and benefits also logged its biggest one-quarter increase this century.

It’s been more than four decades since the U.S. saw a wage-price spiral. For America’s hourly workers, pay has barely kept up with inflation since the 1980s, let alone helped fuel it, a trend underpinned by globalization, falling union membership, and rising automation. Even so, the sheer level of demand in the second half of 2021 should give pause to anyone who thinks U.S. inflation will go away overnight.

The consensus among the economists Bloomberg regularly surveys is that the pandemic may have changed the way we work and shop in an enduring way, but that the basic dynamics of demand and supply will revert to the norm fairly quickly once we neutralize the threat from the virus. Then inflation will start gravitating back toward the Fed’s long-term goal of 2 per cent. If they’re right, policymakers will have managed to steer the U.S. economy to a soft landing and avoid a recession. If they’re wrong, 2023 will be the year we all pay the price.