Mar 5, 2024

BOJ Needs 9 Years to Normalize Balance Sheet, Ex-Official Says

, Bloomberg News

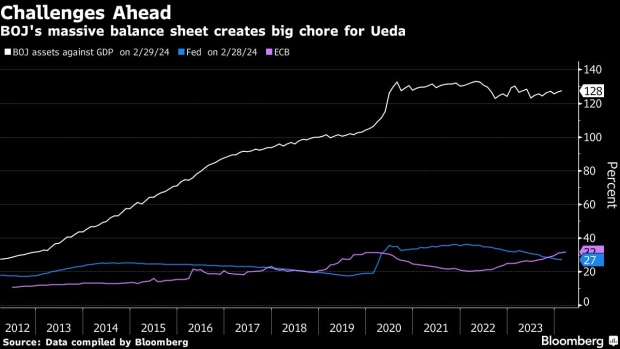

(Bloomberg) -- The Bank of Japan will probably need at least nine years to normalize its balance sheet in the earliest-case scenario after a massive monetary easing program that ran for more than a decade, according to a former executive director.

“The hurdle is very high” for the normalization process, Kenzo Yamamoto, the former BOJ executive, said in an interview Monday. “The BOJ’s balance sheet has changed dramatically. It’s something I’ve never seen anywhere else.”

The BOJ is widely expected to kick off its normalization process this month or in April by ditching the negative interest rate. After that move, the first hike since 2007, how quickly it plans to tackle its bloated balance sheet will be a key question for investors.

As Yamamoto sees it, normalization would mean bringing the balance sheet back to a level where it’s just a little more than required reserves. The bank would have to shed ¥440 trillion ($2.9 trillion) of bonds from its portfolio to reach that point.

“What the BOJ’s normalization means will be a big topic,” Yamamoto said. “If there’s no guidance on that, it would raise the risk of high market volatility in yields, as traders would speculate,” he said.

Less than a quarter of the assets in the BOJ’s portfolio will come to maturity within any given year, according to Yamamoto’s calculations based the bank’s balance sheet in November.

That compares with two-thirds of assets that were set to mature in 12 months in March 2006, when the bank ended a previous five-year period of quantitative monetary easing. At that time, the bank managed to reduce its balance sheet to a normal level in less than half a year.

“You can say that it will take at least nine years, or we are just talking about a dream,” Yamamoto said. His estimate reflects a simple calculation of BOJ’s assets and their maturities that assumes the BOJ doesn’t buy any more bonds or reinvest. Realistically, the bank wouldn’t cut its operations to zero, however, as it aims to keep the market stable, he said.

Read more: BOJ Signals Rate Hike Is Getting Closer, Sparking Yen Rally

“The best way to tackle it is for the BOJ to show a plan for the balance sheet so market players can price that in and send a reminder to politicians and the public not to have excessive expectations for BOJ bond buying going forward,” Yamamoto said. “It’s common sense among central banks that one stops buying assets first and then reduces the balance sheet in accordance with a plan after quantitative easing.”

The Federal Reserve has been shrinking its asset holdings — mostly Treasuries and mortgage bonds backed by government agencies — since June 2022. The current pace allows a maximum of $60 billion in Treasuries and $35 billion in mortgage-backed securities to mature every month without replacement.

As the balance sheet has scaled back more than $1 trillion since its peak, there has been a debate whether the bank is misjudging how far it can shrink its holdings without causing dislocations in places including the repurchase-agreement markets.

Read more: Envisioning the End of Fed’s Quantitative Tightening: QuickTake

BOJ Deputy Governor Shinichi Uchida said last month that the bank hasn’t yet decided on its plan for the balance sheet, and he would have incorporated one in his speech if it existed.

Japan’s loosened stance with regards to fiscal discipline is likely to create another challenge for the BOJ’s normalization efforts. The government is used to issuing debt at almost no costs thanks to prolonged low interest rates. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has pledged to increase spending for childcare and defense, even though he hasn’t yet secured a source of that funding.

Still, the BOJ has said its bond purchases are for achieving the price target, not to finance the government. To prove it, the bank must stop buying bonds and reduce its balance sheet once its goal is met, Yamamoto said.

“The BOJ must draw the line,” Yamamoto said. “Otherwise, once the economy gets weaker, the BOJ is bound to face pressure to buy bonds as it bought so much during the period of large-scale monetary easing.”

Yamamoto said eliminating holdings of exchange traded funds is likely to take longer than normalizing the balance sheet, and it’s getting complicated as the BOJ’s finances are increasingly dependent on revenues from ETF holdings.

“The only way is probably to sell it very gradually,” Yamamoto said. “It will probably take several decades.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.