Feb 7, 2022

Can aging population trends tame inflation?

By Larry Berman

Larry Berman's Educational Segment

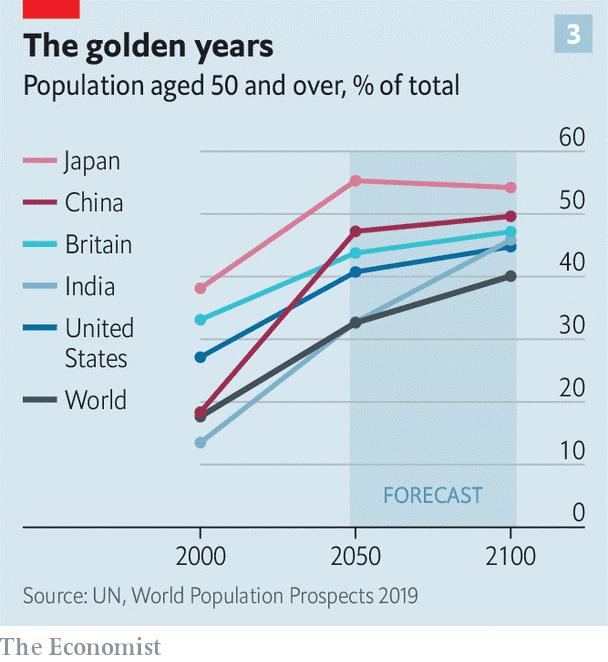

The Economist, one of my favourite weekly reads (or listens these days with audio features), highlights a recent paper examining the effects of demographic change on saving, Etienne Gagnon, Benjamin Johannsen and David López-Salido of the Federal Reserve Board suggest that aging in America may account for about one percentage point of the drop in interest rates since the 1980s. Other research has suggested it could be as much as three per cent. One thing is fact, the world is aging rapidly. Birth rates continue to decline and that will have implications for labour, savings, the cost of money (interest rates), and inflation. The share of global population over the age of 50 rose from 15 per cent in the 1950s to 25 per cent today. It is expected to rise to 40 per cent by 2100 (see chart). Unless young people decide to have larger families on average, the demographic picture will continue to grey. Most expect this to have a mitigating impact on inflation, but some disagree.

We have discussed the impact of demographics for years on Berman’s Call. The demographic impact on your investments can be material. Afterall, aggregate demand, the core driver of GDP, is all about how many people there are, how many are working, how productive they are, and ultimately what they consume. The latest COVID impacts are the affects on the labour market and inflation pressures. If recent fertility trends are anything to go by, India’s birth rate declined to just two children per woman in 2021—below the rate at which births and deaths are in rough balance. India is one of the bullish demographic stories with an average population that is in prime childbearing years (28). Recent history has shown to no surprise, that a growing number of emerging markets have flipped to the slow population growth common in rich countries. Recent research by Matthew Delventhal of Claremont McKenna College, Jesús Fernández-Villaverde of the University of Pennsylvania and Nezih Guner of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona concludes that such transitions—the switch from high mortality and fertility rates to low ones which accompanies economic development—are happening faster over time. The transition took a half century or more 100 years ago, but now tends to be compressed into just two or three decades. Some 80 countries have completed this transition, and in virtually all the rest it is under way. Lower population growth, in theory, should provide slower demand growth. Labour supply shortages driving costs should balance out with more people coming back to the labour force. At least that is the expectation.

COVID accelerated the trend as it depressed birth rates in many countries. China’s birth rate touched a record low in 2021, potentially bringing forward the era of declining Chinese population. This puts China in the Japan bucket in terms of ability to grow. America experienced a baby bust too, which in combination with falling immigration depressed the population growth rate to just 0.1 per cent in 2021—the smallest annual increase on records going back to 1900. To be sure, the end of the pandemic could bring a rebound in birth rates. But there is no mistaking the broader trend: the world is greying, fast.

In an influential book, Charles Goodhart, of the London School of Economics, and Manoj Pradhan, of Talking Heads Macroeconomics, a research firm, argue that the greying of the population will depress interest rates only up to a certain point. Their view rests in part on the observation that while workers on the verge of retirement save heavily, those already retired begin to spend down their stores of stocks and bonds. An increase in the share of the population above retirement age, then, could mean that the proportion of workers in their high-saving years will peak and then decline, dragging down saving and pushing up interest rates.

The colossal spending boom generated by government fiscal and monetary support for COVID may have ignited or accelerated the trend. Financial markets and policymakers are unprepared for inflation driven by labour supply shortages and the accumulated leverage that makes capital market fragility a key focus discouraging central banks from tightening, so inflation is bound to increase. Central bank policy tools are not designed to address supply shortages. Government policy needs to do this and the US Congress seems to be in shock and gridlock, which probably does not change until the mid-term elections in November.

The authors argue that a great demographic reversal seems intuitive, particularly in places like America where an oversize cohort—the baby-boomers—is easing into retirement. Today the average Boomer (1946-1964) is 65. Other economists say there are reasons to expect ageing to continue to depress interest rates. They note, for example, that it is the age profile of a population as a whole which matters. Even as more people retire, the age of the typical working person will continue to rise toward those prime saving years. The median age in America and Canada is still about 39. At this age, women are not having children on average. Another reason is that, in the emerging world, a larger share of workers have their prime saving years still ahead of them. So long as financial markets remain reasonably integrated around the world, higher saving anywhere helps to depress interest rates everywhere.

Spending habits of people in retirement do not tend to spend everything. Rather, for a number of motives—to avoid outliving their savings, or to provide for heirs, among others—they tend to maintain large stocks of wealth well into retirement. This is true for the top percentiles perhaps, but the inequality of central bank policy has led to a huge burden on the bottom half of savers—there is simply not enough savings! Recent work by Noëmie Lisack, of the Banque du France, Rana Sajedi, of the Bank of England, and Gregory Thwaites, of the University of Nottingham, estimates that this habit of leaving behind savings will by mid-century depress interest rates by nearly half a percentage point relative to current levels. But wealth is very concentrated.

The world, in other words, may come to look ever more like Japan. The median age is 48, more than a quarter of the population is over 65, and the yield on a 30-year government bond is a cool 0.8 per cent, despite a government debt load of 259 per cent of GDP and a decade of central banks buying equities and ETFs. As we debate another US CPI report this week and anxiety rips through financial markets, inflation and inflation expectations will remain a key market driver for 2022 and beyond. Understanding demographic influences are a big picture important driver of spending behaviour. We expect inflation is stickier for a few more years, and this should make the next few years payback time from the incredible asset rises in recent years. Don’t look for the inflation of the 1970s though, the demographics suggest otherwise.

Our spring virtual roadshow is starting Feb 24 through April 28. Keep an eye on The Investor’s Guide to Thriving website for more information on how to sign up in the coming weeks.

Follow Larry online:

Twitter: @LarryBermanETF

YouTube: Larry Berman Official

LinkedIn Group: ETF Capital Management

Facebook: ETF Capital Management

Web: www.etfcm.com