Oct 25, 2021

Central Banker Stands Alone With Brazil’s Credibility Crumbling

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Roberto Campos Neto, the head of Brazil’s central bank, had been counting on a certain amount of fiscal discipline from his counterparts across town in the Treasury building. This, at least, is what he repeatedly told investors in recent months as they grew anxious about the new social spending programs that President Jair Bolsonaro was talking about unleashing.

Last week, Campos Neto’s public assurances slammed into the harsh reality of life in Brasilia on the eve of an election year. Bolsonaro, desperate to boost his approval ratings, announced a program that was so big and broad that it triggered a week-long rout in financial markets and the mass resignation Thursday night of four key members of that vaunted Treasury team.

The wild succession of events is now heaping pressure on Campos Neto himself. As he prepares to begin a two-day policy meeting tomorrow, traders in Sao Paulo are looking to him and his fellow board members as the last line of defense against runaway inflation and a looming currency crisis. Even Economy Minister Paulo Guedes made it clear the burden is now on the central bank, saying on Friday that the monetary authority will have to “run faster” to not fall behind the curve.

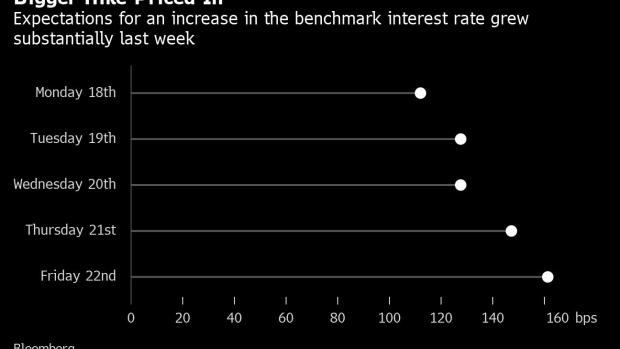

Speculation is mounting in futures markets that policy makers will lift the 6.25% benchmark interest rate by more than one percentage point at the meeting. Even for a central bank that has earned a reputation as one of the most hawkish in the world after five straight hikes, this would be bold. It’d be the biggest increase in Brazil in nearly two decades.

The question is whether in a country where so many things out of Campos Neto’s control are going wrong, can he actually stem the tide on his own? And can interest-rate hikes alone break the inflation fever and calm down investors?

“It looks very challenging for the central bank to reach its goal in 2022 without favorable deflationary shocks,” said Mauricio Oreng, senior economist at Banco Santander Brasil SA. He foresees inflation, now running at an annual clip of more than 10%, to slow to 5% next year before nearing the 3.25% target in 2023. But that’s as long as interest rates reach double digits by early next year. Most analysts see inflation at 4.4% next year.

BRAZIL REACT: Bolsonaro, Guedes Double Down on Populism

The bank had already promised to keep raising the benchmark rate by 100 basis points a meeting until inflation expectations returned to target, but economists now say that pace looks too dovish if policy makers are to deliver on their pledge to do “whatever it takes” to rein in prices.

“To keep an unwavering commitment to their 2022 inflation target, central bankers need to surprise the market and accelerate their tightening pace,” said Mariana Guarino, portfolio manager at Truxt Investimentos, a Rio de Janeiro-based asset manager. That could mean raising rates by as much as 2 percentage points on Wednesday, she added.

Traders in interest-rate futures are already pricing in a 162 basis-point increase this week, while analysts at major Wall Street banks such as Morgan Stanley expect the Selic to rise by at least 125 basis points. JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Barclays anticipate a 150 basis-point jump. The last time Brazil saw rate increases of such magnitudes was in late 2002, just before Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva took office.

“Considering Brazil’s central bank reaction function up to now, we do not discard an even more aggressive move this week to front-load the cycle as they decide whether to acknowledge formally that the latest developments would trigger a fiscal regime shift,” wrote JPMorgan analyst Cassiana Fernandez.

Stagflation Risk

The trouble is that while bigger-than-expected rate hikes may be ineffective to bring inflation to next year’s target, they risk snuffing out a fragile economic recovery.

Much of Brazil’s current inflation is explained by prices that barely respond to monetary policy: Food, fuel and electricity. On top of that, Bolsonaro’s proposed cash handouts of 400 reais ($70.8) a month to about 17 million poor families is likely to increase demand for basic items, making them more expensive.

Brazil’s economic recovery was already expected to lose steam next year even as the service sector reopens, with about half the population of 210 million fully vaccinated against Covid-19. After 425 basis points worth of interest rate hikes since March, most analysts forecast gross domestic product to expand a mere 1.4% in 2022, with some warning any growth will be a result of statistical carry-over.

Read More: Brazil Ex-Central Bankers See Above-Goal Inflation for Two Years

“If central bankers raise the Selic by what’s priced in by interest-rate futures, Brazil will enter a recession in 2022,” said former central bank director Tony Volpon, now an investment strategist at Wealth High Governance, an asset manager in Sao Paulo. “What we are witnessing is a tightening of financial conditions that’s negative for the economy.”

Currency Meltdown

Failure to aggressively tighten monetary policy, however, could leave the country more vulnerable to a currency crisis. The real has weakened more than 3% last week, the worst performer in emerging markets after the Turkish lira. It has lost about 8% of its value against the dollar so far this year, despite Brazil being a commodity exporter that was supposed to benefit from rising prices of raw materials.

The currency losses are part of a broad repricing of Brazil’s risk by investors who are now disillusioned with promises of fiscal discipline made by the government. Intervention by the central bank, which holds more than $330 billion in foreign reserves, would be futile in such a scenario, according to Caio Megale, chief economist at XP Inc. and a former member of Guedes’s team.

“If the central bank were to intervene, it would only lose reserves and still prove unable to change the direction of the market,” he said.

The next few days will be crucial for Brazilian assets as the government is expected to detail how much it’s planning to spend beyond its spending ceiling, a rule that limits the growth of public expenditures to the previous year’s inflation rate.

Yet there’s little doubt about the country’s deteriorating fiscal fundamentals.

“How they break the fiscal ceiling matters, but the big picture is that the rule is easy to break,” said Alvaro Mollica, emerging markets strategist at Citigroup Inc.

(Updates Santander forecast in sixth paragraph, JPMorgan revised forecast for interest rates in ninth paragraph)

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.