Jul 26, 2021

Debt-Limit Deadline Leaves Democrats Weighing Options for Fix

, Bloomberg News

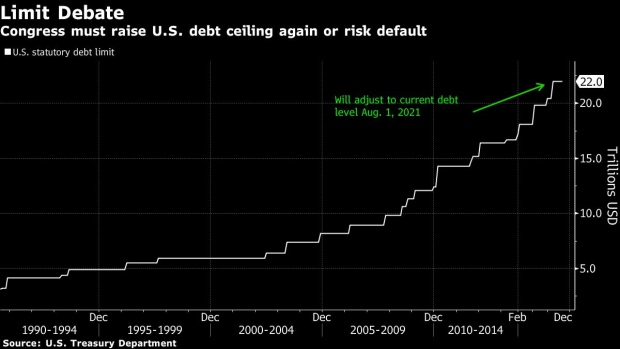

(Bloomberg) -- Democrats who control Congress are expressing confidence they can raise the federal debt limit in time to avoid a default this fall, but exactly how and when they’ll act isn’t yet clear.

They have a rough deadline: the Congressional Budget Office last week said it expects so-called extraordinary measures available to the Treasury Department, like temporarily withholding special bonds from federal retirement accounts, will give Congress until October or November to act before the government runs out of money.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned Friday of a payment-default risk soon after Congress returns from its recess in September, though she said she couldn’t provide a precise date for how long special measures would last.

Powerful Democratic senators including key moderate Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Finance Committee Chairman Ron Wyden of Oregon, as well as Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders of Vermont, said in hallway interviews at the Capitol last week they expect Congress to avert a crisis. Speaker Nancy Pelosi insisted the debt limit would be addressed in a Sunday appearance on ABC’s “This Week.”

Many traders and strategists are taking Democrats at their word and expect Congress to eventually reach a ceiling deal. But the anticipated fireworks, combined with the precariousness of the virus situation, large and volatile government expenditures and questions over the extraordinary measures themselves, make for a lot of uncertainty.

Here’s a look at Democrats’ options:

1. Budget Reconciliation

This is the one route for Democrats to do it on their own, since it can’t be blocked via Senate filibuster and therefore needs no Republican votes. The House and Senate would pass a budget resolution teeing up so-called “reconciliation” bills enacting President Joe Biden’s long-term economic agenda along with increasing the debt ceiling.

The main drawback is political: Democrats would own an unpopular debt-limit hike without any cover or votes from the GOP.

This is Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell’s preferred route. The Kentucky lawmaker warned last week he didn’t expect any Republicans to vote for a debt-limit hike that would enable more spending. That in turn incensed Democrats, who helped provide votes for trillions in fresh debt under former President Donald Trump despite opposing his tax cuts.

“We should not have a double standard where there’s one kind of response for a Republican president and another response for President Biden,” Wyden said.

But Republicans are already blaming Biden for the recent inflation spike, and they want Democrats to own both inflation and a national debt expected to top $30 trillion heading into 2022’s pivotal midterm elections.

A Democratic aide said it’s an open question whether the Senate parliamentarian would allow the debt limit to simply be suspended for a period of time -- as Congress lately has preferred to do -- or if Democrats would have to back a specific number for a debt-limit increase. A number lends itself better to GOP political television ads attacking Democrats.

2. Standalone Bill

If Democrats bring up a standalone debt-limit suspension in the Senate without using reconciliation, Republicans would be on the spot. They could face a political risk if they blocked something essential to the ordinary function of government.

The GOP would then face a choice: block the bill with a filibuster, risking turmoil in the markets, or allow it to have an up-or-down vote. A single Republican senator can force a 60-vote threshold, however, so 10 Republicans would likely have to walk the plank to end a filibuster.

In 2014, when President Barack Obama refused to give Republicans any concessions in return for a debt-limit hike, the standoff finally ended with McConnell and other senior Republicans voting to end a filibuster led by Ted Cruz of Texas. That let Democrats proceed with a simple-majority vote.

Some Republicans, including Lindsey Graham of South Carolina, the Budget Committee’s top GOP member, have discussed trying to attach budget-related legislation aimed at shrinking the deficit over time to any debt-limit increase. Democrats, however, aren’t in a mood to give concessions in return for what they consider to be simply allowing the government to pay bills racked up in part by the GOP.

3. Budget Agreement

In addition to the $579 billion bipartisan infrastructure deal and a separate $3.5 trillion Democratic plan consuming most of Washington’s attention, both parties still need to hammer out an agreement on regular government appropriations for the next fiscal year, which begins Oct. 1.

Previous debt-limit hikes have occurred as part of deals setting caps on such regular spending, and Republicans do have things they want in such talks that give Democrats potential leverage too -- like higher defense spending than Biden proposed.

4. Tying to Must-Pass Bill

Democrats could try to jam Republicans by tying the debt limit to other must-pass bills, like the stopgap bill that will be needed to keep the government open after Oct. 1.

If Republicans filibuster such a combination, they could face blowback for a shutdown and any financial turmoil that follows. An October 2013 shutdown fight sparked by Cruz’s effort to defund the Affordable Care Act eventually ended with Republican capitulation, with a reopened government and a debt-limit hike.

But this could be risky for Democrats, given that they control both chambers in Congress and the White House and have the power to avert a debt-limit crisis on their own.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.