May 12, 2022

Democrat in Gym Shorts Maps Path to Senate Through Trump Country

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- John Fetterman didn’t look like a typical Senate candidate when he rolled into Pennsylvania’s Lebanon County on a recent Saturday wearing gym shorts and an oversized Carhartt hoodie coated in dog hair.

But that’s the point. Fetterman, with a beatnik-style goatee and tattoos, is out to prove that conventionality has been a loser for Democrats in the small towns and rural hamlets that he thinks are ripe for recapture from Republicans.

“Some people are like, ‘Why are you going to Lebanon? It’s so red!’” Fetterman, imitating a high-pitched squeal, told a crowd of about 90 people who came to see him at an outdoor meet-and-greet. “That’s exactly why we’re going to Lebanon.”

The 52-year-old lieutenant governor is seeking to replace the retiring Republican Senator Pat Toomey, giving his party a rare opportunity to pick up a seat in an uphill battle to maintain control of the Senate. His progress is being closely watched across the country for clues to whether Democrats can stanch their loss of support outside urban areas.

“The question is whether his anti-establishment persona, that style, is going to be able to attract those moderate, independent and even some Republican voters,” said John J. Kennedy, a political science professor at West Chester University who’s written three books on Pennsylvania politics. “That’s the bet he’s making. And if Democrats nominate him, that’s the bet they’re making.”

He has so far campaigned in 55 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, including ones former President Donald Trump won in 2020 by more than 30 percentage points. It’s a risky strategy, given Fetterman’s support for liberal causes such as legalizing marijuana, expanding government health care and protecting abortion rights and transgender kids. As lieutenant governor, he’s championed criminal justice reform and second chances for long-time inmates.

“It’s a very progressive agenda,” said Sam Farmer, a 74-year-old retired salesman from Lancaster, after hearing Fetterman speak in Lebanon, about 30 miles east of Harrisburg. “I worry about how public he is about legalizing marijuana.”

His wife, Cathy Farmer, a retired advertising executive who describes herself generally as a “right-to-life” voter, was impressed nevertheless. “I’m a registered Republican,” she said. “He has done everything he said he would do, and whether or not I believe in everything, I believe he’s being honest with the people.”

Earlier: Fetterman’s Opponents Go on Attack in Pennsylvania Senate Debate

With a bald head and imposing 6-foot, 8-inch frame, Fetterman is hard to miss in a crowd. He played offensive tackle at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania, then went on to get an M.B.A. from the University of Connecticut and a master’s in public policy from Harvard University.

He is campaigning as a “yinzer,” the folksy name that working-class Pittsburghers give themselves based on their tendency to call each other “yinz” instead of “you.”

Fetterman is up by more than 30 points in recent polls against his leading opponent, Conor Lamb, who eschews media coverage as much as Fetterman embraces it.

Lamb, a centrist Democratic congressman from the Pittsburgh suburbs, is working within the party establishment, picking up scores of endorsements from Democratic elected officials, labor unions and women’s rights groups. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s editorial page backed him, citing electability and lingering questions over a 2013 incident when Fetterman, then the mayor of Braddock, chased and held a Black man for police after mistakenly thinking he’d heard gunshots.

The May 17 primary also includes state Representative Malcolm Kenyatta of Philadelphia.

There are also fears that Fetterman’s colorful persona could backfire outside of western Pennsylvania in the general election, where the leading Republican opponents include a Trump-backed celebrity physician, Mehmet Oz, former Bridgewater Associates Chief Executive Officer David McCormick and political commentator Kathy Barnette.

“I think that look can cut both ways, especially with some suburban voters,” said Mike Mikus, a Democratic campaign strategist from Pittsburgh who’s not involved in this campaign but worked for an opponent of Fetterman’s in a previous primary run for the Senate in 2016. “There may be a sense that they don’t take him as seriously as a Conor Lamb.”

Moreover, western Pennsylvania’s working-class, union voters have always been more culturally conservative, and a possible Supreme Court decision overturning abortion rights could make it harder for either side to attract crossover voters.

“It’s all cultural issues now,” said Kennedy, the West Chester University professor. “Without that labor tie, without that union tie, the vacuum is filled by these cultural issues -- guns, abortion, same- sex marriage.”

Read More: Pennsylvania Abortion Fight Reveals Instability of Swing States

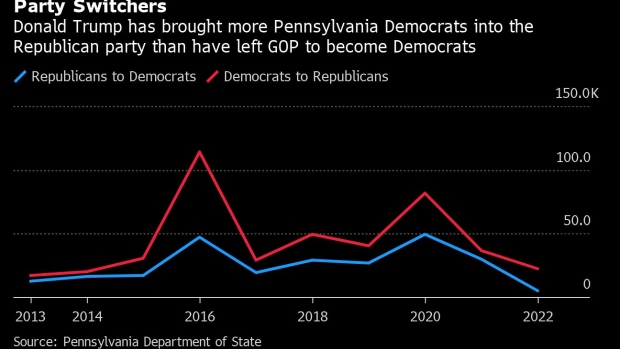

Fetterman is undaunted. He said he doesn’t have to flip every county on the map from red to blue. But he is hoping to reduce the margins, both by winning over some former Democrats and energizing remaining Democrats who have become demoralized after watching all their neighbors support Trump. “If we let red counties go 80-20 in this race, Democrats are going to lose. We just can’t,” he said.

Winning back Trump voters, he said, means a general-election campaign focused on the issue that helped Trump win them over in the first place: trade. Braddock, a majority-Black town of 1,700 people in the Pittsburgh suburbs, is the home of the last U.S. Steel Corp. plant in the region. He and his wife and three school-aged children still live there rather than in the lieutenant governor’s mansion.

“I will never be somebody that believes we don’t need to keep making s--- in this country. Pardon my language,” Fetterman told reporters outside an Italian restaurant in Wilkes-Barre during a campaign swing. “We need to make sure that we are unapologetically pro-American in our trade deals.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.