Jun 22, 2020

‘Everything Is Expensive’ as Global Stock Valuation Debate Rages

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Three months after the sharpest sell-off in history, Wall Street is freaking out about valuations once more.

Bank of America Corp. clients are sounding the alarm on stock prices like never before -- nearly 80% of them said in a survey the market is overvalued even as they sink cash into the market in droves. Bears are finding new reasons to bristle at forward price-to-earnings ratios at historic extremes, while bulls hit back with more reasonable interpretations of multiples, often relative to other asset classes.

“Everything is expensive,” wrote Chris Watling, chief market strategist at Longview Economics, in a note Friday. “80% of the markets we track have a valuation in the upper quartile relative to the market’s history -- the greatest percentage on record using data since the mid-1990s.”

While renewed signs of global growth could push multiples even higher, strategists at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. including Christian Mueller-Glissmann concede that “elevated valuations will likely become a speed limit for returns again.” The question is, just when will those fundamental thresholds have been breached?

Here are some of the measures investors are debating:

Dotcom Deja Vu

After a more than 40% climb in stocks from the trough of the coronavirus-driven slump in March, global equity valuations have surged to their highest since the dotcom bubble of the new millennium.

The MSCI AC World Index is trading close to a commanding 20 times forward estimates for the next year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

U.S. Premium

While valuation concerns are not limited to the world’s biggest stock market, multiples in the U.S. are getting the bulk of the attention.

For good reason. If you slice and dice equal-weight gauges of the S&P 500 and MSCI World Indexes, the premium for an “average” U.S. share surged to the highest in at least a decade after the peak of the coronavirus outbreak. It has yet to come back to its historical range.

History Lesson

There’s no need to reignite old arguments over the use of Yale professor Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio -- the newer debate is over how to interpret it. Bears would point to the gauge of U.S. stock prices relative to 10-year average earnings as being at levels synonymous with the dotcom bubble and roaring ‘20s. Bulls would note the measure is well off peak levels from 20 years ago.

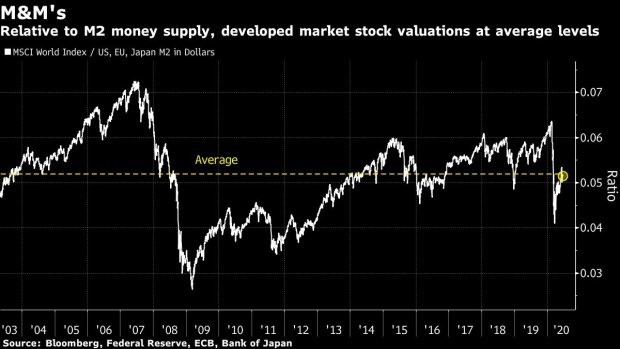

Money Supply

Given the truly unprecedented level of monetary policy support fueling financial markets, some commentators have suggested traders should heed different measures to value equities to incorporate central bank largesse. Tom McClellan, editor of the McClellan Market Report, chooses to look at U.S. stocks relative to the level of money supply -- M2. Broadening this approach to include the increase of such a measure in Europe and Japan shows global stock valuations are bang on their average of the last 18 years.

Versus Bonds

This year’s risk-asset sell-off and rush to havens saw a surge in the spread of global dividend yields to benchmark Treasuries, a closely watched gauge for income investors. But that was before a spate of dividend cuts as companies sought to bolster their balance sheets to deal with the impact of the pandemic. Now that analysts have had time to adjust their dividend expectations, the measure of attractiveness of global equities over Treasuries has fallen back, but remains at levels favorable to stock bulls.

Versus Credit

Comparing the world’s stocks to their credit cousins suggests valuations are more or less back to normal. The spread between the yield-to-worst on the Bloomberg Barclays Global High Yield Index and the dividend yield on the MSCI AC World Index, which soared at the height of the crisis, has retreated to just above its average of the last ten years.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.