Sep 28, 2022

Fed Boosts Risks of Hard Landing With No Rate Pause at Hand

, Bloomberg News

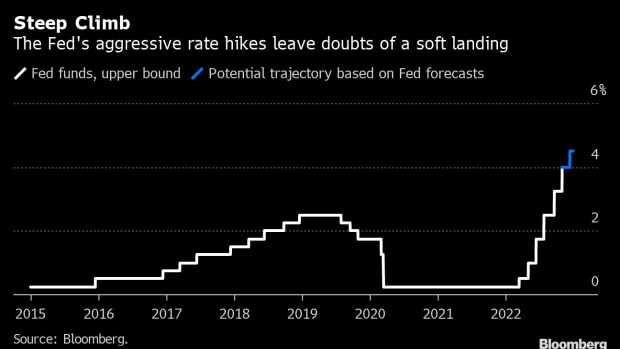

(Bloomberg) -- Fast and furious Federal Reserve tightening risks slamming the economy into recession, with economists worrying it’s committing another error after being slow to respond to rampant inflation.

A string of jumbo-sized 75 basis-point interest-rate increases, which the Fed signals it will continue in November, means officials are not waiting to see the effect of their action before moving again.

“They’re moving so fast there’s not a lot of time to evaluate the impact on the real economy,” Jonathan Pingle, UBS Group AG chief economist, said Wednesday on Bloomberg Television. “Given the lags for some of these inflation data, that’s kind of a concern.”

The Fed has raised rates by 3 percentage points this year, with the bulk of that coming since June, and has vowed to continue hiking until it sees clear signs that inflation is coming down.

While that has already pushed up the cost of borrowing on everything from home loans to cars, the full impact of these moves likely won’t be known for months given the time it takes for monetary policy to work through the economy.

By not building in some breathing room to see if the actions they’ve already taken are bringing down inflation, policymakers risk causing a bigger slowdown than necessary and potentially more harm than needed in the labor market.

Fed officials indicated at their meeting earlier this month that they’ll raise rates by another 1.25 percentage points this year, which could mean another 75-basis-point hike in November and a half percentage-point increase in December. Rates will then go up another quarter point next year, according to the Fed’s median projection.

Such a move in November would mark the fourth straight three-quarter-point hike. This risks trapping the Fed “in a hamster wheel of large rate increases” Evercore ISI economists Krishna Guha and Peter Williams wrote in a note after the Fed’s September meeting.

The economy, which has so far appeared fairly resilient to the Fed’s actions, is starting to show some signs of cooling demand. Apple Inc. is reversing plans to increase iPhone production amid lower demand than it had anticipated.

Policymakers, who view their role in bringing down inflation as critical to their credibility, have acknowledged that this amount of tightening is likely to cause pain to US households and businesses. The Fed can only directly impact the demand side of inflation, or how much spending power -- or appetite for spending -- people have, so a key channel to curb that is via higher unemployment.

But the labor market has been strong in the past year, with unemployment low and many more job openings than people looking for work. That should help it weather some of the Fed’s actions, policy makers argue. Still, it’s a delicate balance.

“Trying to navigate that to bring inflation down while we do so as gently as possible, not to tip unnecessarily the economy into a downturn that actually influences the full employment part of our mandate, is a struggle,” San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly said in a virtual event Tuesday evening.

She said it’s important that the Fed “navigate through this high inflation environment as carefully as we can” so as to not cause long-term damage to the labor market.

Even a relatively small impact to the labor market -- the Fed currently estimates that the unemployment rate will rise to 4.4% later next year from 3.7% now -- will mean lost jobs for more than a million people. Past crises have shown that losing a job during a downturn and long bouts of unemployment can have lasting implications, sometimes lifelong, for impacted workers.

Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said he’d like avoid overdoing it on rate hikes by stopping before inflation gets down to the Fed’s 2% target.

“I don’t think it’ll be appropriate for us to continue to tighten and increase your rates until inflation gets to 2%,” Bostic said Wednesday. “That will be guaranteeing that we’ve gone too far and we’ll take the economy into a negative space.”

That may prove difficult to execute in practice. By not slowing down rate hikes right now, the Fed is also in danger of not being able to justify the pause it has penciled in for next year if inflation remains high at that point, according to Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont.

“Officials are clearly laying the groundwork to end their rate hikes at a point where the rate of inflation is still far too high,” Stanley wrote in a note last week. “I am skeptical that the financial markets and the general public are going to be willing to go along for the ride, with the Fed having little to show for its efforts at that time in terms of getting inflation down.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.