Nov 8, 2022

Hungary Becomes EU’s New Inflation Hotspot as Food Prices Spiral

, Bloomberg News

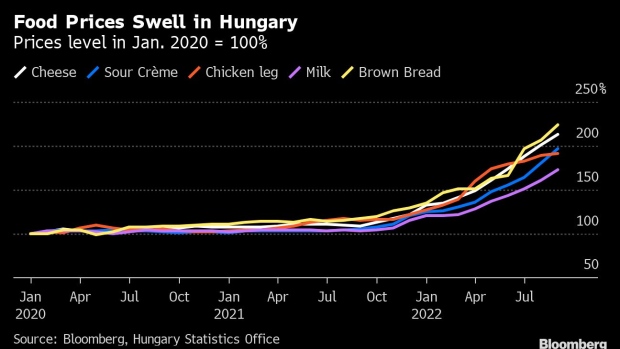

(Bloomberg) -- Hungary, which has seen the biggest increases in food costs in the European Union, is becoming a new inflation hotspot among the bloc’s 27 member states.

The government announced on Wednesday that it was expanding price caps on five food staples to include eggs and potatoes. It unveiled the steps after data showed annual price growth increased by a full percentage point in October to 21.1%. Hungary is closing in on the three Baltic states with the fastest inflation in the EU.

Inflation is the “biggest problem” in Hungary, Cabinet Minister Gergely Gulyas told reporters on Wednesday after a government meeting. The retail price of eggs and potatoes will be capped at their Sept. 30 levels, he said.

Surging food prices, in addition to soaring utility costs, are powering inflation in Hungary. Household energy prices rose 64%, while food costs advanced 40%, more than double the EU average. The prices of bread, cheese and eggs have almost doubled in the past year, with the latter rising 92% from the same period in 2021.

The rising costs have hit hospitality businesses, including the upscale Bobo eatery in Budapest managed by Gergely Haris, who has raised prices so many times recently that he no longer remembers the latest off the top of his head.

“In the past we used to import food from abroad because of quality reasons,” said Haris, who manages his family’s restaurant. “Now it’s because of the price. The difference is stunning.”

Hungary’s inflation is likely to peak at an annual 25% by year-end, Economic Development Minister Marton Nagy told Inforadio on Monday.

The increase is prompting Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s government to expand price caps introduced in the past year that also include food staples such as cooking oil, as well as household energy, gasoline and even mortgage rates.

The government is fighting price increases partly stoked earlier this year by its own pre-election stimulus package. Prices were also affected by a severe drought, which curbed Hungary’s harvest, and windfall taxes imposed on retail grocers.

Adding to inflation concerns, price-growth looks set to be entrenched across the economy, with high wage growth also fueling it. Core inflation, which strips out volatile food and energy price swings, was actually higher than the headline rate in October at an annual 22.3%.

Next year, Hungary faces a combination of a recession and inflation stuck at elevated levels, Raffaella Tenconi, an economist at Wood & Co., said in a report published Tuesday.

That may force the central bank to keep the key short-term interest rate at an EU-high 18% until the middle of next year, she said.

Some restaurants have already folded given the increased food and overhead costs. At Bobo, which caters to more affluent clients, Haris has toyed with the idea of replacing forint prices with euros to make them look less daunting.

The price of a schnitzel has risen 76% since he and his parents opened the restaurant just before the Covid pandemic. It’s now priced at 7,900 forint ($20), though the website still lists it at 5,900.

“We’re all just trying to figure out when the pace of price increases will slow,” he said. “We need that to happen to plan for the future.”

--With assistance from Marton Kasnyik and Zoe Schneeweiss.

(Updates with new food price caps in second and third paragraphs.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.