Feb 4, 2021

Italy’s Used to Bringing Central Bankers In When Politics Fails

, Bloomberg News

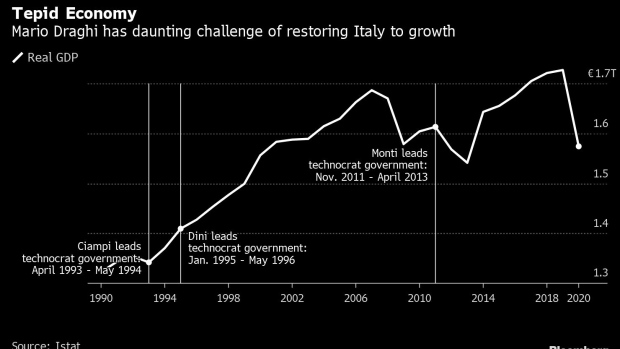

(Bloomberg) -- Every time Italy is about to go off the rails, there’s always been the same solution: call in the technocrat. Former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi is the latest in a long list of fixers.

That’s when you know things are really bad, either because the finances are in such disarray that bond markets are panicking or because the usual bickering among parties has turned into complete political gridlock. It’s a peculiar way for a western democracy to function, especially since the outsider brought in to solve the most intractable of problems is unelected by the people.

But like Italy’s tradition of revolving-door governments, the reasons are rooted in the country’s past. The founding fathers of the postwar constitution wanted to ensure that Italy’s parliamentary system would be fully inoculated against the threat of dictatorship. If the price to pay was a proliferation of parties and unruly coalitions, then so be it.

That is why the head of state, a ceremonial role in normal times, becomes critical during a crisis. When there is no way out, and elections are too risky, he can make the call and appoint an expert. In accepting the challenge, Draghi said “it was a difficult moment.”

“It’s a way out when the system breaks down,” said Stefano Silvestri, a political analyst and advisor to governments who served under Lamberto Dini’s technocratic government in the 1990s.

This is the fourth time in three decades that a technocrat is appointed to address the country’s various dysfunctions. And usually it always comes as a relief to investors and disillusioned Italians. They have a year or two to make the kind of painful and unpopular cost cuts that politicians are loathe to do. When the job is done, the country goes to the ballot box.

In Draghi’s case, if he can negotiate the support he needs from Italy’s fragmented parliament, the job won’t be to slash but to build. And he’ll have over 209 billion euros ($251 billion) of cash coming in the next few years via the European Union recovery fund to help him.

He’ll need to show a common touch as well. The pandemic has not only devastated the economy, it’s also traumatized the nation. Italians are still haunted by images of coffins in line for the morgue in the city of Bergamo.

They have terrible memories of their last technocratic government led by economics professor and former European Commissioner Mario Monti, whose tax hikes and tough pension reform aimed at producing financial stability were deeply unpopular.

“Monti’s austerity backfired contributing to the rise of populist parties like the Five Star Movement, it reinforced negative feelings against experts perceived as a privileged elite,” said Sofia Ventura, professor of political science at the University of Bologna.

Read More: Something Has Snapped in Italy’s Stormy Relationship With Europe

The habit of placing technocrats in power started after an entire political class was wiped out by a series of corruption scandals in the 1990s. In the immediate aftermath, former central banker Carlo Azeglio Ciampi stepped in to stabilize things.

It happened again in 1995, following the fall of Silvio Berlusconi’s first government. That is when Lamberto Dini, another economist and Bank of Italy man, stepped in. The country’s central bank has produced most of Italy’s technocratic leaders, including Draghi.

Then in 2011, after Berlusconi’s last government fell apart, with bond yields at historic highs, Monti was called in. But this time, the technocrat left a damaging legacy.

‘Consummate Politician’

The image of an unemotional, gray-haired man in a sharp suit was jarring to an impoverished country. He was seen as too close to Brussels, a stickler for imposing debt and deficit rules. This was the moment when euroskepticism began to really take root in Italy in what was a dangerous political shift for one of the EU’s founding members.

While Draghi will need to overcome those negative associations, he’s got one thing going in his favor. The pandemic has popularized government intervention across the world, and most administrations in Europe are engaging in state aid and support in various forms to keep their economies running.

“He’s a highly skilled operator, a consummate politician and we know he’ll do “whatever it takes” to steer Italy out of its worst economic and health crisis since the war,” said Neil Wilson, chief market analyst at trading platform Markets.com. “As far as technocrats go, you won’t find a better one.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.