Sep 19, 2021

Merkel’s Reign Has Done Little to Help Germany’s Working Women

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The developed world’s longest-serving female head of government, Angela Merkel, has done little to improve the lot of Germany’s working women.

Although female labor-force participation in Germany is higher than the average for industrialized nations, a significant part of the women in the country work part time -- a level that has barely budged on Merkel’s watch. The share of women working part time has gone from 38.8% in 2005, the year Merkel got elected, to 36.3% in 2019, according to OECD data. In Sweden that ratio was 17.3% while in France it stood at 20.4%.

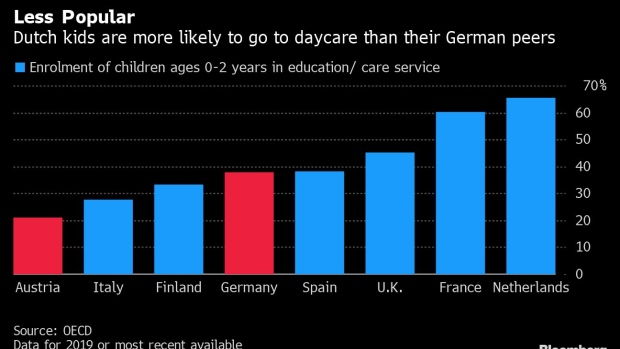

The system in Germany -- like in its German-speaking neighbors Austria and Switzerland -- is stacked against women, especially those with children. It includes a tax regime that critics say discourages two-career families, a lack of affordable daycare and a tradition that frowns upon the practice of sending children to full-day kindergarten.

As Merkel prepares to step down after the Sept. 26 German elections, she will be leaving behind a country where it’s still not easy for women to pursue ambitious careers. Despite ample research demonstrating the benefits of a diverse workforce, Merck KGaA is the only company listed on the blue chip DAX index with a female chief executive officer.

Germany came in below average in the European Women on Boards Gender Diversity Index for 2020, ranking 12th out of 18, behind the U.K, the Netherlands, and Spain. Austria ranked 14th, while Switzerland was second to last.

“I see it as a missed chance since the topic could’ve evolved much further under such a great chancellor,” said Monika Schulz-Strelow, head of Berlin-based advocacy group Women for Corporate Boards. “Women in high positions often don’t want to be associated with these ‘women’s issues.’”

Although Merkel remains extremely popular, including among female executives, she has only sporadically championed diversity issues during her 16 years in office. She did touch on the topic at a film premiere this year, conceding that “much still needs to be done” to address gender inequality in Germany.

A Bertelsmann Foundation report found that having children shrinks a German woman’s lifetime earnings by as much as 62%, not least due to having to work part time, while it had practically no effect on men’s. The discrepancy persists even in the face of analysis by the Council on Foreign Relations that noted that if women’s labor-force participation in Germany and Switzerland was equal to that of men, gross domestic product would get a boost of more than 20% in each country.

“We’re simply foregoing many goods, many resources, and that’s absolutely detrimental to the economy,” said Jutta Allmendinger, president of the Berlin Social Science Center. “Change only happens when pressure is actually exerted by women themselves. It does not happen on its own.”

European Commission President Urusla von der Leyen -- a doctor and a mother of seven -- ascended the ranks of German politics under Merkel, who doesn’t have any children.

But her rise is an exception and masks the fact that Germany, Austria and Switzerland share structures that inhibit women from pursuing a career, much less pushing into the upper echelons in the workplace. These include tax rules that penalize double-income households, daycare facilities lagging behind other nations, rules that grant non-working spouses free social security benefits and a generous pension for widows.

Culture also plays a role: The German language even has a term for women who supposedly neglect their children -- calling them “raven mothers.”

“If I were to work full-time, as a mom, people would judge me for it,” said Jessica Fey, a 34-year-old employed part-time at a bank in rural Germany, where the daycare options aren’t sufficient for her three-year-old son. “People assume you are prioritizing your career over your kid, without knowing the real reasons that might be behind your decision.”

While French children are sent to state-run daycare from an early age, in German-speaking countries such options are limited or expensive.

German parents will be entitled to full-day care for their elementary school children only from 2026. In the Swiss canton of Zurich, a Credit Suisse Group AG report found, a middle-income family could face an annual bill in excess of 20,000 francs ($21,700) for two days a week of childcare. An Austrian survey from 2018 found that among parents who forwent childcare services, a quarter cited the expense.

The OECD in 2017 urged Switzerland to boost productivity by making childcare affordable and shifting to an individual rather than household-based tax system. Neither issue has been addressed.

Germany has taken steps ostensibly to help women, such as raising the minimum wage. Yet its joint income tax and benefits system, which the OECD has criticized for penalizing households with a second employed person, remains in force. Shifting to individual taxation could boost employment by 200,000 full-time jobs, the Munich-based Ifo Institute estimates.

Slow Reform

Although about half of university graduates across the German-speaking region are women, there are few signs that the problem of too-few-women in business leadership are reversing. A study of Germany’s biggest listed firms by the Allbright Foundation, published in June, found that firms created recently were even more male dominated than their older counterparts.

The government has tried to address the imbalance by legislating quotas for the executives of large companies, with new rules kicking in this year.

But for some, like Miriam Beblo, a professor of economics at the University of Hamburg, the Merkel administration has just not gone far enough.

Merkel “has promoted individual women, though not so much sweeping changes to the law,” she said. “It’ll probably take another four years” to change the income tax regime.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.