Feb 29, 2024

Pig-Butchering scams netted more than US$75 Billion, study finds

, Bloomberg News

Canada is leading the way for global crypto regulation: Coinflip crypto ATM CEO

Pig-butchering scammers have likely stolen more than US$75 billion from victims around the world, far more than previously estimated, according to a new study.

John Griffin, a finance professor at the University of Texas at Austin, and graduate student Kevin Mei gathered crypto addresses from more than 4,000 victims of the fraud, which has exploded in popularity since the pandemic. With blockchain tracing tools, they tracked the flow of funds from victims to scammers, who are largely based in Southeast Asia.

Over four years, from January 2020 to February 2024, the criminal networks moved more than $75 billion to crypto exchanges, said Griffin, who has written about fraud in financial markets. Some of the total could represent proceeds from other criminal activities, he said.

“These are large criminal organized networks, and they’re operating largely unscathed,” Griffin said in an interview.

Pig butchering — a scam named after the practice of farmers fattening hogs before slaughter — often starts with what appears to be a wrong-number text message. People who respond are lured into crypto investments. But the investments are fake, and once victims send enough funds, the scammers disappear. As far-fetched as it sounds, victims routinely lose hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. One Kansas banker was charged this month with embezzling $47.1 million from his bank as part of a pig-butchering scam.

The people sending the messages are often themselves victims of human trafficking from across Southeast Asia. They’re lured to compounds in countries including Cambodia and Myanmar with offers of high-paying jobs, then trapped, forced to scam, and sometimes beaten and tortured. The United Nations has estimated more than 200,000 people are being held in scam compounds.

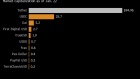

The study, “How Do Crypto Flows Finance Slavery? The Economics of Pig Butchering,” was released on Thursday. Griffin and Mei found that $15 billion had come from five exchanges, including Coinbase, typically used by victims in Western countries. The study said that once the scammers collected funds, they most often converted them into Tether, a popular stablecoin. Of the addresses touched by the criminals, 84 per cent of the transaction volume was in Tether.

“In the old days, it would be extremely difficult to move that much cash through the financial system,” Griffin said. “You’d have to go through banks and follow ‘know-your-customer’ procedures. Or you’d have to put cash in bags.”

Paolo Ardoino, the chief executive officer of Tether, called the report false and misleading. “With Tether, every action is online, every action is traceable, every asset can be seized and every criminal can be caught,” Ardoino said in a statement. “We work with law enforcement to do exactly that.”

Tether has cooperated with authorities in some cases to freeze accounts tied to fraud. But often by the time the crime is reported, the scammers have already cashed out.

“Our paper shows they’re the currency of choice for criminal networks,” Griffin said.

Chainalysis Inc., a blockchain analysis firm, also said the study’s totals might be inflated. Just because a blockchain address receives some money from a pig-butchering scam doesn’t mean all the money received by that address comes from fraud. “Quantifying funds earned through pig-butchering scams is challenging given limited reporting,” said Maddie Kennedy, a spokesperson for Chainalysis. Tether is a one of the company’s customers.

Many of the fraud victims’ blockchain addresses were collected by Chainbrium, a Norwegian crypto investigations firm. Chainbrium also conducted its own analysis of the data and found that a large proportion of the funds flowed through a purportedly decentralized crypto exchange called Tokenlon. Scammers use the exchange to obscure the source of the funds, according to Chainbrium. Tokenlon didn’t respond to a request for comment.

“People in the US, their money is going straight to Southeast Asia, into this underground economy,” said Jan Santiago, a consultant to Chainbrium.

Eventually, the criminals would send the scam proceeds to centralized crypto exchanges to cash out for traditional money. Griffin said Binance was the most popular exchange, even after the company and its founder, Changpeng Zhao, pleaded guilty in November to criminal anti-money-laundering and sanctions charges and agreed to pay $4.3 billion to resolve a long-running investigation by prosecutors and regulators.

“Binance is the place where they can move large amounts of money out of the system,” Griffin said.

Like Tether, Binance has worked with law enforcement in some cases to freeze accounts tied to fraud and return money to victims. A spokesman for the company said it recently worked with authorities to seize $112 million in a pig-butchering case.

“Binance continues to work closely with law enforcement and regulators to raise more awareness of scams, including pig butchering cases,” the spokesman, Simon Matthews, said.