Mar 1, 2024

Russia Uses Price Floor for First Time to Protect Government Oil Revenue From Sanctions

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Moscow has for the first time ever activated its so-called price floor mechanism to shield the flow of petrodollars to its state budget from Western energy sanctions.

The nation’s oil producers are footing the bill, underscoring how protecting the flow of petrodollars into state coffers is a key priority for the Kremlin. Russian oil and gas industries generate around a third of total budget revenue — several billions of dollars every month — and Moscow is using the money to finance its war against Ukraine and to raise social spending ahead of presidential elections in March.

To calculate their January oil taxes, Russian energy firms had to use an average price of Urals — the nation’s main export crude blend — of $65 a barrel, according to a letter from the Federal Tax Service published last month. The state budget will receive this revenue in February, with figures due to be published next week.

The market price of the crude was actually lower, but the government applied a $15-a-barrel discount to the Brent benchmark for Urals in the tax formula, according to Bloomberg calculations based on data from Argus Media Ltd., which were confirmed by a Russian official who spoke on condition of anonymity.

The actual discount at which the nation’s producers were selling their Urals cargoes averaged $18.12 per barrel at Russian ports in January, the data show.

The Group of Seven industrialized countries and their allies have targeted Russia’s state oil revenue, while aiming to keep barrels flowing onto global markets, by imposing a $60-a-barrel price cap on the nation’s exports of crude and oil products. Moscow has successfully blunted the impact of this by selling barrels to Asian clients and deploying a massive shadow fleet of tankers to evade restrictions on shipping and insurance.

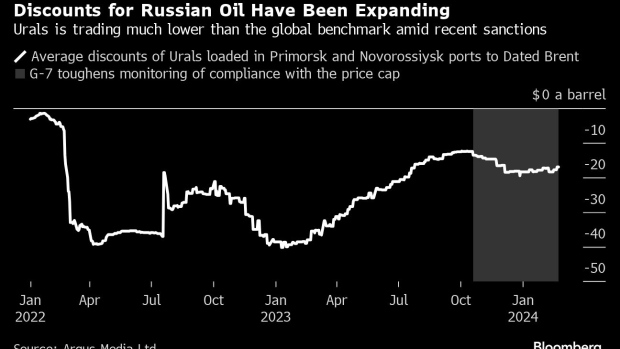

In recent months, the G-7 has intensified the pressure on shipowners, traders and oil buyers to enforce compliance with the price cap, resulting in a deeper Urals discount. The $18 price gap recorded by Argus in January is narrower than at some points in early 2023, when Urals sold in some of Russia’s western ports for $40 less than Brent, but is still six times wider than the typical pre-invasion level of about $3.

These figures reflect the price of Urals in key Baltic ports of Primorsk and Ust-Luga, plus the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. They represent the so-called free-on-board cost of the crude, which excludes the cost of shipping and insurance required to deliver the crude to its buyer.

As Russian barrels reach their end-customers in Asia, the price at the point of delivery more closely approaches that of Brent. However, the final value includes shipment, insurance costs and payments to intermediaries, with the opaque nature of the trading making it difficult to estimate exactly how many dollars per barrel of crude sold that Russian oil producers get to pocket.

The Russian authorities also have a second way of calculating the Urals price for budget purposes — taking the average Argus price of a Urals barrel in the key Russian western ports and adding virtual costs of shipping it to Rotterdam and the Mediterranean. For now, those costs are set at $2 a barrel, giving a lower valuation than the price floor for January, but the nation’s antitrust watchdog has said it will develop a more intricate calculation.

Each month the tax authorities will compare the two Urals assessments and use a higher value to tax oil producers.

In its response to Bloomberg on Russian oil-price calculations, the nation’s finance ministry referred Bloomberg to the Economy Ministry. The latter and the nation’s tax service didn’t respond to requests for comments.

Tougher Approach

The price-floor was introduced last year at a much wider discount of $34 that narrowed steadily to $20 in December. Until now, that meant Russian oil taxes were calculated using actual market pricing. The government plans to further narrow the price-floor discount to $10 next year and $6 in 2026.

As the tax formula gets tougher, the pressure will grow on Russian oil producers to negotiate higher Urals prices with their foreign clients or pay the additional taxes out of their own pocket.

The government expects the Urals discounts to narrow “as soon as the supply chain improves and the market calms down,” according to Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak. Yet the G-7 plans to tighten its squeeze on Russian energy revenue through tougher enforcement of the price cap, according to a statement on Feb. 24 following a videoconference to mark two years since the invasion of Ukraine.

(Updates with chart after 10th paragraph)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.