Apr 7, 2020

Scandal Follows Crisis After 35 Bond Funds Shuttered in Sweden

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The liquidity crunch that shuttered 35 bond funds in Sweden last month has revealed some disturbing truths about the country’s credit market.

As the spread of Covid-19 across Europe triggered a sell-off in corporate bonds, investors keen to withdraw their savings in Sweden suddenly learned they couldn’t.

While the Swedish funds were legally entitled to suspend trading to ensure fair treatment for all their customers -- a process known as gating -- it now seems clear that investors weren’t aware of the risks they faced. The episode has sparked calls for funds to drastically adjust their marketing practices.

“It’s reprehensible that some corporate bond funds have marketed themselves as an alternative to savings accounts,” said Frida Bratt, a savings economist at Nordnet Bank AB. But many investors “haven’t realized there’s a whole different risk level involved.”

Per Nordkvist, Director of Conduct Supervision at Sweden’s Financial Supervisory Authority, said that “in retrospect there will surely be reasons to go back and analyze, to see if there are any improvements in the regulations that need to be made.”

Bratt says the kinds of fact sheets that such funds offer investors “can be problematic, as they use risk metrics that are misleading.” The information available to investors gives “the impression that a fund carries low risk because it has low volatility, while it may in fact reflect very low liquidity in some of the holdings,” she said.

Bratt points to Spiltan Fonder AB, which drew attention after marketing its Fixed Income Fund (Räntefond Sverige) as a “low risk” option for investors that also includes money market instruments. It was the last of the Swedish funds to reopen for trading at the end of March and its larger holdings included high-yield issuers Intrum AB and Volvo Car AB, as well as unrated real estate companies such as Klovern AB.

Spiltan’s sales manager Niklas Larsson says it was problems in the wider corporate bond market that forced many credit funds to postpone trading in March. The fund has provided “a good return at a very low risk, while bank accounts have hardly given any interest,” he said in emailed comments.

The industry’s representative body has some sympathy with bond fund investors, pointing out that many were left wrong-footed by the severity of last month’s sell-off. And while there are laws governing what goes into fact sheets, the Swedish Investment Fund Association admits there is an issue with how risk is presented.

“It’s based on historical price fluctuations in the fund,” the association’s chief executive officer Fredrik Nordstrom said. “But in an economic upturn some risks, such as credit and liquidity, are not visible in the key figures.”

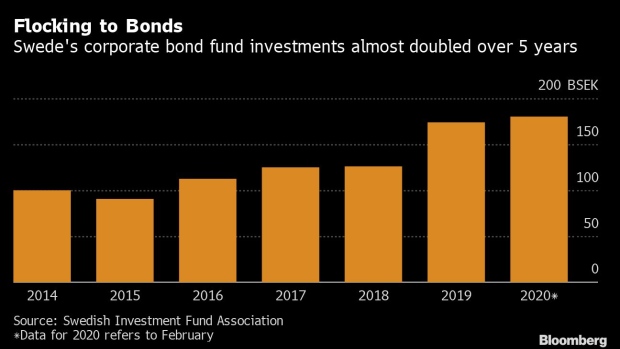

Investor appetite for products that offer above-average returns has soared in recent years, after ultra-low interest rates became the norm. Since 2015, investments in corporate bond funds have nearly doubled to about 180 billion kronor ($18 billion), according to the Swedish Investment Fund Association. Volumes are likely to be even higher if funds with a mixed-asset strategy are included, the data suggest.

But the huge demand has created an imbalance, given the relatively small pool of assets in the corporate bond market in Sweden (where companies tend to rely more on bank financing than the bond market). Meanwhile, the industries behind the biggest growth in issuance are some of the riskiest. Last year saw a spike in bond sales from real-estate firms, especially junk-bond issuers.

As a result, a lot of credit asset managers have been left holding similar securities with little opportunity to churn positions in a primary bond market frozen by the Covid-19 pandemic. These unfortunate dynamics became painfully clear when 35 funds in Sweden suddenly were forced to halt trading, more or less in unison.

That concentration risk is also reflected in how banks buy and sell corporate bonds in the secondary market. In the recent sell-off bank trading desks have been keen to avoid mark-to-market losses on their books as they hold the same securities as fund managers, according to Fredrik Edlund, who runs Captor Fund Management AB in Stockholm.

So last month, when funds were faced with investors wanting to cash-in their savings, the bank desks “chose to value their trading stock of bonds at far higher levels than where they were prepared to buy,” Edlund said in an interview.

But if the screen prices set by banks don’t reflect reality, Edlund says “that creates problems for managers” who cannot then accurately determine a fair net asset value for the fund.

There is however limited scope for national regulators to change the rules governing the fund industry, due to directive harmonization within the European Union, according to the Swedish FSA.

“We nevertheless participate in ESMAS’s work where many issues of this nature can be discussed to achieve harmonized supervision,” Nordkvist said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.