May 25, 2022

'The Last Hired': How the Labor Market Is Changing for Black Americans

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- For Black Americans, job prospects have improved since 2020. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that the gains eked out over the past two years -- since the murder of George Floyd prompted a national reckoning over race -- appear as fragile as ever. Indeed, inflation is threatening to upend progress in the labor market as policymakers respond to a backlash against rising prices.

While the uprisings that drew thousands into the streets in 2020 helped put disadvantages of Black workers in the spotlight, most experts instead point to government aid and the tight US labor market during the pandemic as driving the collective advances for them and other groups.

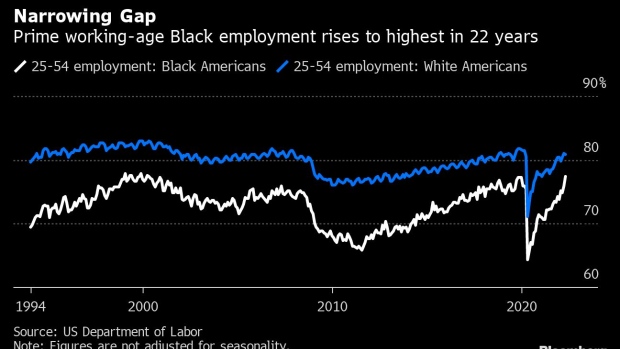

One key measure tracked by economists shows that employment of Black Americans of “prime working age” — 25 to 54 — jumped to 77.4% in April, the highest in 22 years. While that’s still well below the equivalent measure for White Americans, the uptick has reduced the gap between the two figures to the narrowest on record, in data stretching back to 1994.

It’s a sign that the hottest job market in generations is making it “more costly for firms to discriminate against African-American job applicants,” according to Algernon Austin, the director for race and economic justice at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington.

The Black unemployment rate has also returned to pre-pandemic levels. After the 2008-09 recession, it took nine years for Black unemployment to return to levels that prevailed before the downturn. This time, it only took two.

The figure stood at 5.9% in April -- below the 6% registered for the group in February 2020 before Covid-19 shuttered businesses across the US.

Yet the economic divide between Black and White persists. And, for many, the hope inspired by Black Lives Matter has been drained away by other racist killings, including this month’s mass shooting in Buffalo.

The unemployment rate for Black women, among the hardest-hit workers in the initial months of the pandemic, has plunged to 5% from 16.6% in May 2020. But that’s still well above the 2.8% rate seen by White women.

“On the whole, we’re seeing that frankly a lot of Black workers are able to take advantage of the tightness of the labor market and strong employer demand to get jobs that would have taken much longer to get in other past downturns,” says Joelle Gamble, the chief economist at the US Department of Labor.

Read more: A Report Card on Race: How Far We’ve Come, How Far We Have to Go

Part of the difference this time around relates to the response by the US government and the Federal Reserve.

Instead of choosing a long, drawn-out recovery with all of its disproportionate consequences for Black Americans -- like they did in the 2008-09 recession -- lawmakers stepped in during Covid outbreaks with massive financial support for US households, transferring trillions of dollars to them via stimulus checks and greatly-expanded unemployment insurance programs. That underwrote ongoing consumer spending in the economy, which in turn provided a foundation for rehiring those newly thrown out of work.

“In this recovery, we’re less likely to see scarring from workers being unemployed for long periods of time,” Gamble says.

Black employment also may have received a boost this time due to the unusual impact the pandemic had on hiring at an industry level, according to Evgeniya Duzhak, an economist at the San Francisco Fed.

Duzhak found, in an analysis posted to the bank’s website on May 16, that Black unemployment didn’t go up on a relative basis during the pandemic as much as would have been expected. That’s “partly because over 25% of Black men are employed in production, transportation, and material moving occupations, and those occupations fared better than the service sector.”

But now, the progress risks coming undone in an all-out effort to tame inflation.

Economic policy makers in the White House and at the Fed are shifting their priorities from rebuilding the workforce toward curbing price pressures through austerity measures -- which threaten to slow or even reverse recent employment progress.

Republicans and Democrats including Senator Joe Manchin eschewed President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better, a wide-ranging package that included several job creation initiatives and would have added more in public spending, citing the need to quell inflation.

Perhaps even more important is the central bank’s response. Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues have embarked on a rapid tightening cycle and are warning that inflation-fighting via higher interest rates will probably push up the unemployment rate, and may even ultimately induce another recession.

For observers like William Spriggs, the Howard University economics professor and chief economist for the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations, that poses an existential risk to the entire effort of building a more inclusive economy, the need for which has been dramatically underscored by the events of the last two years.

“We’re still going to be the last hired, so if you increase the unemployment rate, you just undo all the gains,” Spriggs said. “What’s the point of the tight labor market? It is the necessary condition for Black advancement.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.