Apr 5, 2023

To Fix China Fiscal Crisis, Experts Call for Taxes, Asset Sales

, Bloomberg News

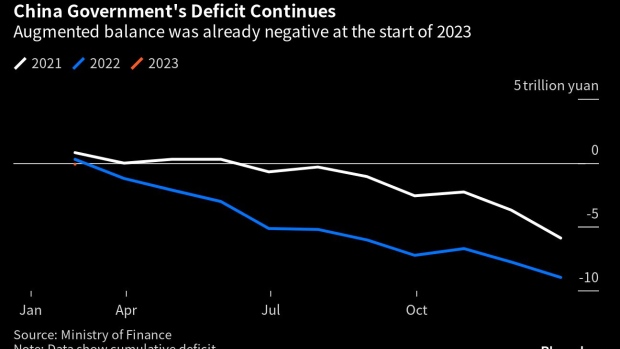

(Bloomberg) -- China’s provincial governments are facing unprecedented debt burdens following a collapse in land sales, a slowing economy and increased spending on Covid testing and lockdowns over the years.

Investors are becoming increasingly worried about the massive debt pile, which Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimated this week has reached $23 trillion — or 126% of GDP — if off-budget borrowing by local governments are included. Curbing local debt risks was also highlighted by President Xi Jinping as a key challenge officials must tackle this year.

The issue has been a topic of discussion at several high-profile business forums in China recently, with government advisers and economists setting out remedies on how to curb the debt and get public finances back on a firmer footing. Here’s a look at some of their suggestions in more detail.

Property Tax

Lou Jiwei, a former finance minister, recommends imposing a property tax to help boost revenues, arguing that local governments “don’t really have many other sources of tax income to add” to their current portfolio.

China has been talking about rolling out a nationwide property tax to control soaring prices for over a decade but the progress has been slow. A trial began in Shanghai and Chongqing in 2011, and it wasn’t until 2021 that the parliament authorized the program be expanded to more cities — although that is yet to happen, with a historical slump in the country’s real estate market putting those plans on hold.

At a conference in January, Lou said a property tax will be a sustainable source of income for local governments and suggested it can wean authorities off their reliance on revenue from selling land. He expressed a similar view in an article published in March online by the Comparative Studies magazine.

“Property tax is the most suitable to be a local tax. The trial should be conducted as soon as possible after economic growth normalizes,” he wrote.

Restructuring the Bureaucracy

Li Yang, a former adviser to the People’s Bank of China, suggests trimming down the layers of government as part of an “institutional reform.”

“Such reforms will involve cutting redundant jobs, adjusting government functions and surely will face challenges,” Li, who is now chairman of the National Institution for Finance and Development, a government think tank, said on the sidelines of the China Development Forum in March.

China currently has five levels of public administration with the central government at the top, followed by 31 provinces, hundreds of cities, thousands of counties, and tens of thousands of townships at the bottom. The bureaucratic system has long been criticized for low efficiency and costly over-staffing.

Streamlining the government isn’t rare. In a campaign initiated in the 1990s, China reduced nearly 10,000 townships through merging, laying off more than 86,000 employees.

The National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic-planning agency, proposed in 2006 to raise the status of counties in budget control to that of cities and put township budgets under the management of counties — an overhaul that would essentially cut the five levels of fiscal governance to three.

China had a total of 7.19 million civil servants at the end of 2016, with about 200,000 added in that year alone, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security reported at the time. It hasn’t updated the figure since. Including those employed by nonprofit making organizations such as schools, hospitals and research institutes, the number of employees on the government payroll could be several times as large.

Asset Sales

The government can also sell assets to repay borrowing, Li said. “The share of government assets in the economy is rising,” he said during a speech to the CDF. “We will be able to solve the debt problem if we can do some work in swapping the assets for debt.”

China’s outstanding infrastructure investment — which can be roughly taken as the value of the assets — has totaled 184 trillion yuan ($27 trillion) since 2001, Orient Securities Co. analyst Zhao Xuxiang estimated in a report in January.

Beijing revved up a call last year for officials to accelerate the so-called “revitalization of assets” in clean energy, transportation, rental housing and other sectors. Listings of infrastructure-backed real estate investment trust products are encouraged, as a way to help contain local debt risks and expand the funding sources of public facilities in future.

Transfer Payments

While revenues tend to concentrate at the higher-level governments, spending responsibilities are often borne by lower-level governments, particularly counties. As a result, counties and townships rely heavily on transfer payments from the top.

Transfer payments by Beijing to local levels to pay for education, health care and other general spending are expected to hit 10 trillion yuan in 2023. That’s equivalent to 86% of the income local governments are expected to earn from taxes and fees this year, up from 66% in 2015.

The financial aid will have to continue and keep increasing before long-term reforms to boost local government income is done through measures such as the property tax and changes to the central-local tax sharing system.

“More transfer payment from central to local — not only the revenue but also funds raised through borrowing — is the only way out in the short term,” said Ding Shuang, chief economist for Greater China and North Asia at Standard Chartered Plc.

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.