Oct 15, 2022

Torched Stocks Are About the Only Thing Working in Fed’s Favor

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Inflation shows few signs of cooling in the economy. The same cannot be said of markets, which are starting to seem like the only thing the Federal Reserve has going for it these days.

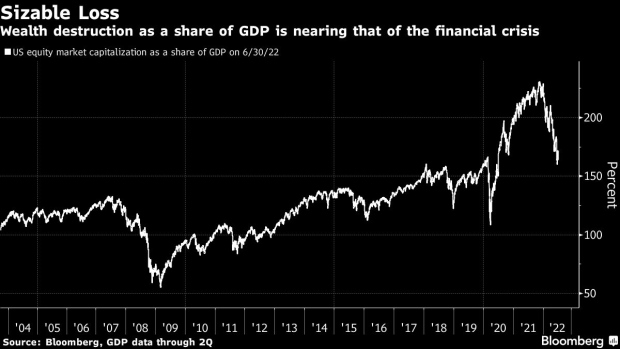

Even with Thursday’s big bounce, the S&P 500 has lost a quarter of its value this year. Shocking as that’s been for investors, it’s one of the few things happening anywhere that actually accords with the Fed’s goal of draining the economy of bloat. Recently, the toll in terms of wealth destroyed -- about $15 trillion to date -- has started to approach that of the 2008 financial crisis, when measured against US gross domestic product.

And while the stock market isn’t the economy, it’s a signal and an input into it, affecting everything from consumer sentiment to the price of private enterprises. Declines on a par with what’s already happened in equities have been a decent proxy for reversals in inflation more than a dozen times since the late 1950s, according to research from Doug Ramsey, chief investment officer at the Leuthold Group.

“The wealth effect played a greater role than it ever had in inciting the inflationary spiral, and it’s also going to play a great role in reducing it,” Ramsey said in an interview at Bloomberg’s headquarters in New York. “When you think about the stock market declining in conventional percentage terms on the index, that understates the amount of wealth that it wipes out.”

Buttressed by easy-money policies and massive fiscal stimulus, the S&P 500 more than doubled between its pandemic low and this year’s high, making Americans who owned stocks feel richer, if only on paper. All that has changed in 2022, with the Fed raising rates at the fastest pace in decades.

Plunging equity prices wiped 4.1% off Americans’ aggregate net worth to $144 trillion in the quarter ending June 30. That was the second-biggest decline since 2008.

It hasn’t taken a notable toll on consumer psyches yet, with Thursday’s reading on consumer prices for September showing stubbornly high inflation. By Ramsey’s logic, it will someday, helping the central bank achieve its goals. A more frugal consumer won’t be the only force behind moderating inflation -- which also depends on interest rates and moves in the dollar -- but it may help.

The scope of the hit to wealth in this rout is getting harder to ignore. Between its November record and late last month, the Wilshire 5000 Index had plunged about 27%. Expressed as a percentage of GDP, the loss equals to 54%, close to the 61% that evaporated during the financial crisis, data compiled by Leuthold show.

Tumbling asset prices have historically shown a track record of either alleviating inflationary pressures or signaling their reduction.

Between 1957 and last year, the S&P 500 had posted 15 corrections of 19% or more. In 10 of the cases, inflation was lower 12 months later, declining an average 2.3%, according to data collated by Leuthold.

And it’s not just the stock market. Rising borrowing costs have roiled aspiring home buyers, making home ownership -- a big source of wealth for Americans -- out of reach for some. The affordability of housing is deteriorating at a faster pace than at any point in the past three decades, estimates compiled by Morgan Stanley show.

“Much of Americans’ wealth resides in home equity and financial-market portfolios, both of which have taken big hits this year,” Ed Yardeni, founder of his namesake research firm, said in a note to clients. “We see red flags in the weakness of the housing market, the negative wealth effect, and the strength of the dollar.”

Bridgewater Associates LP’s Bob Prince painted a somewhat extreme scenario over the summer, saying the Fed’s attempt to pursue two goals -- bring down inflation while avoiding an unacceptably deep recession -- could cause policymakers to pause their rate-hiking cycle, eventually doing two rounds of tightening instead of one.

This scenario, currently off-charts for the market, “presents the greatest risk of massive wealth destruction,” the firm’s co-chief investment officer said in note.

While painful in the short run, the decline of the equity market’s size relative to that of the economy can be seen as a healthy development for market bulls.

Plunging asset prices have finally pushed the stock-market capitalization relative to national gross domestic income out of the top quintile of historical readings, which has preceded equity declines in the next year, three and five years, data compiled by Ned Davis Research show.

“The wealth effect is being felt not only in equities and financial markets, but also housing prices going down,” Mona Mahajan, senior investment strategist at Edward Jones, said in an interview. “That diminished wealth effect is what can be a self-fulfilling cycle: consumers may rein in their purses, and that has a ripple effect on the economy. We may be getting there.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.