Jun 24, 2019

Trump muses privately about ending postwar Japan defense pact

, Bloomberg News

President Donald Trump has recently mused to confidants about withdrawing from a longstanding defense treaty with Japan that he thinks treats the U.S. unfairly, according to three people familiar with the matter.

Trump regards the accord as too one-sided because it promises U.S aid if Japan is ever attacked but doesn’t oblige Japan’s military to come to America’s defense, the people said. The treaty, signed more than 60 years ago, forms the foundation of the alliance between the countries that emerged from World War Two.

Even so, the president hasn’t taken any steps toward pulling out of the treaty, and administration officials said such a move is highly unlikely. All of the people asked not to be identified discussing Trump’s private conversations.

Exiting the pact would jeopardize a postwar alliance that has helped guarantee security in the Asia-Pacific, laying the foundation for the region’s economic rise. It would also risk spurring a fresh nuclear arms race as Japan would need to find another way to defend itself against threats from China and North Korea. Under the terms of its surrender in World War Two, Japan agreed to a pacifist constitution in which it renounced the right to wage war.

Meeting With Abe

The president will make his second trip to Japan in a matter of weeks on Wednesday when he travels for the Group of 20 summit in Osaka. He’s expected to again meet with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who enjoys as good a relationship with the mercurial and unpredictable American president as any foreign leader.

Yet as with many U.S. allies, there are growing tensions between the countries over Trump’s attitude toward trade. The president has said he may enact tariffs on imports of foreign cars, calling them a threat to national security -- an allegation called preposterous by automakers and many U.S. lawmakers.

It’s unsettled in American law whether the president can withdraw from a ratified treaty without congressional approval. President George W. Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002 without lawmakers’ consent.

Trump regards Japan’s repeated efforts to move a large U.S. military base in Okinawa as a sort of land-grab, the people said, and has raised the idea of seeking financial compensation for American forces to relocate. Trump’s focus on the U.S. defense pact with Japan may foreshadow broader scrutiny of American treaty obligations across the world, two people familiar with the matter said.

The president has said in private conversations previously that he has Japan’s back and is aware of the U.S.’s obligations under the treaty. But, as with his stance on other multilateral agreements, he wants the relationship to be more reciprocal.

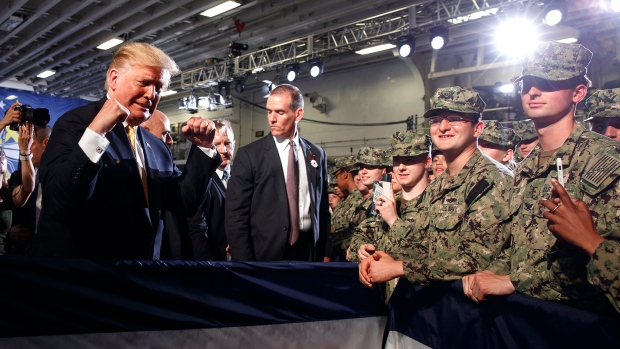

“The U.S.-Japan alliance has never been stronger,” Trump told sailors and Marines last month aboard the USS Wasp, an amphibious assault ship at the naval base in Yokosuka, shared by the U.S. and Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. “This remarkable port is the only one in the world where an American naval fleet and an allied naval fleet headquartered side by side, a testament to the ironclad partnership between U.S. and Japanese forces,” he said.

At the same time, the president has long expressed skepticism of arrangements such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the United Nations. He withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement and the Paris climate accord, both agreed by President Barack Obama, and has re-negotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The U.S. defense treaty with Japan was first signed in 1951 along with the Treaty of San Francisco that officially ended World War Two. The defense pact, revised in 1960, grants the U.S. the right to base military forces in Japan in exchange for the promise that America will defend the island nation if it’s ever attacked.

For decades after the war, Japan refrained from developing offensive capabilities such as long-range bombers, aircraft carriers and nuclear weapons. But Abe, a relatively hawkish leader, believes his nation should take a more robust role in its own defense. He pushed through a controversial interpretation of the constitution to allow Japanese forces to come to the aid of allies.

Japan is buying advanced F-35 fighter planes from the U.S. and will fly some of them off warships effectively refashioned as aircraft carriers, its first since the war. In May, the country’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party recommended the government eventually raise defense spending to about 2 per cent of gross domestic product, in line with NATO recommendations for its members and a threshold Trump has said should be a minimum for U.S. allies.

‘Cornerstone of Peace’

There are presently about 54,000 U.S. military personnel based in Japan, a permanent troop presence that allows the U.S. to more easily project force across the Pacific. U.S. Forces, Japan, calls the arrangement “the cornerstone of peace and security in the Pacific” on its website.

It isn’t clear how those forces would be affected if Trump withdrew from the treaty. The president has frequently complained that U.S. allies hosting American bases don’t pay enough money for what he considers a privilege, and he could seek to negotiate a new or revised treaty that entails more Japanese financial support for the U.S. military presence.

While the president did not refer to the base by name in his recent conversations, there has been a running dispute surrounding Marine Corps Air Station Futenma on Okinawa. The American presence has been controversial for more than two decades, since three servicemen raped a 12-year-old Okinawan girl in 1995. Local people still attribute the presence of the base to higher rates of crime and accidents in the area, according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

Withdrawing U.S. forces entirely from Japan would hand a strategic victory to American adversaries China and North Korea.

James Carafano, vice president of foreign and defense policy studies at the Heritage Foundation, said he doubts the U.S. will withdraw from the treaty with Japan.

“There’s nothing that says we have to abide by treaties for all eternity,” Carafano said. “I just doubt we will revisit U.S. policy on the U.S.-Japan strategic alliance,” which he also referred to as the “cornerstone” of U.S. foreign policy in Asia.

Abe reached a deal in 2013 with Obama to move the base out of Okinawa as early as 2022 if a replacement could be constructed. But Trump believes the land underneath the base is valuable for development, and has told confidants the real estate could be worth about US$10 billion, the people said.

He considers the situation another example of a wealthy country taking advantage of the U.S., the people said.