Jan 17, 2024

Ukraine Allies Have to Outspend Russia to Win War, Estonia Says

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas said Ukraine still has a path to victory and allies can help it defeat Russian forces by contributing a chunk of their economic output to the war effort.

Every member of the so-called Ramstein group — more than 50 countries including all 31 members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization — should channel the equivalent of 0.25% of their gross domestic product to Kyiv annually, Kallas said. That would raise at least €120 billion ($131 billion) and swing the conflict in Ukraine’s favor, she said.

“If we do things right, then there’s no point in those grim predictions,” Kallas said in an interview in Tallinn on Tuesday. The Estonia plan — ambitious for NATO members already falling short of defense-spending targets — would offer a sustainable source of funding for Ukraine, she said.

After almost two years of war, Ukrainian authorities are grappling with wavering support among allies as more than $100 billion in US and European Union funding is held up amid political infighting. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy made an urgent plea this week, telling the World Economic Forum that assistance to Kyiv is an investment in Western security.

Kallas said she’s circulating the quarter-percent figure, which was first pitched by the Estonian Defense Ministry in December and is being adopted by the government in Tallinn, as a way of putting a price tag on Ukraine’s war effort. Extending the policy across the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, an alliance of Ukrainian allies that first met in April 2022 at Germany’s Ramstein airbase, would turn the tide for Kyiv, Kallas said.

“Nobody wants to give a check when you don’t know what it’s going to cost,” Kallas said, acknowledging weariness among allies. “If we concentrate our efforts now, then the breaking point for Russia could not be very far.”

The mood has shifted in Kyiv after a months-long counteroffensive fell short of its aim to break through entrenched Russia lines last year and a funding shortage increasingly looms. But Kallas, who has warned of Russia’s existential threat to her own NATO nation of 1.3 million, said the outcome hinges on the Kremlin, which is also feeling the strain.

“It also depends on the war fatigue on Russia’s side, because they see their people coming back in coffins,” Kallas said, adding that Moscow is running out of financing to prop up its war machine.

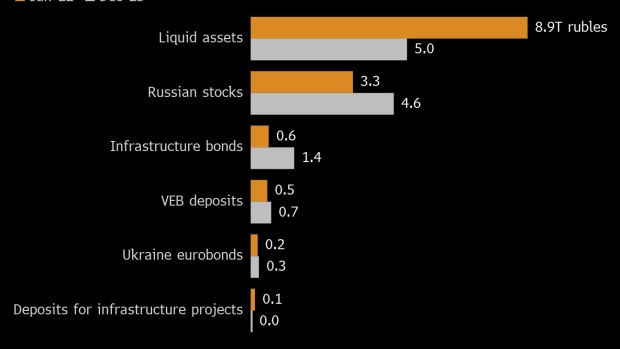

That observation aligns with Russian Finance Ministry data, which showed that the government’s wealth fund has tapped almost half of its reserves. Its holding of cash and investments that can be easily liquidated slumped to 5 trillion rubles ($56.5 billion) at the end of last year from 8.9 trillion rubles before the war, ministry data indicated. Total holdings fell almost 12% to 12 trillion rubles.

Estonia’s Defense Ministry estimates that the war costs Russia at least €10.2 billion in military outlays a month, compared with €5.3 billion spent on average by Ramstein members. Estonia’s plan would match Russian spending, which the ministry says is “more than sufficient” for success.

“Their economy is in a bad state and their budget is in a bad state,” Kallas said. “They can’t raise outside capital because the Chinese are not lending them. And there are sanctions.”

The Estonian premier also issued a warning ahead of the Russian election in March, in which President Vladimir Putin is seeking re-election. She said she anticipates “unpopular decisions,” including a potential new mobilization and tax increases to fund the war effort.

‘Have to Do More’

Kallas warned that failure to defeat Moscow on the battlefield would leave Russia with more territory and embolden Putin to pursue new military campaigns that could put him in direct conflict with NATO in the future. A report last year from Estonia’s foreign intelligence agency estimated that Russia’s military could recover from the conflict within three years.

Kallas, who’s expressed interest in succeeding NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg when he leaves the post in October, lamented what she sees as a low level of defense spending in the alliance.

Many members are falling short of a 2014 pledge to invest 2% of GDP in defense. A stronger show of European commitment could also shore up political support from the US at a time when a new Donald Trump presidency could rattle the alliance.

“I think because this war seems very far away and, and some leaders might still think that you don’t have to spend that on defense because the threat is not that real,” Kallas said. “We as Europe have to do more.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.