Jul 29, 2019

AMLO plows forward in Mexico brushing off neoliberal scorn

, Bloomberg News

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador hasn’t stopped to rest since winning office in a landslide last July.

He speaks pretty much every weekday at 7 a.m. from the presidential palace in Mexico City, making announcements and taking countless questions from press. Before that, he meets with his security team at 6 a.m. to assess the latest crime numbers. On weekends, he flies coach outside of the capital city to far-flung places like Zongolica, Veracruz and Huejutla, Hidalgo, to meet with locals and sell his social policies, which include direct cash transfers to the elderly and youth.

In his eight months in power, Lopez Obrador, 65, has broken with the mix of stiffness and pomposity that have characterized his predecessors. He ditched the dozens of bodyguards that traditionally accompanied the Mexican president and closed the 5,000-square-foot residence that has housed 14 of the country’s leaders since 1934. In tune with his austerity mantra, he put the presidential airplane on sale and hasn’t traveled abroad. He skipped a Group of 20 leaders’ meeting in Osaka last month, on the grounds that he was too busy dealing with Mexico’s domestic problems.

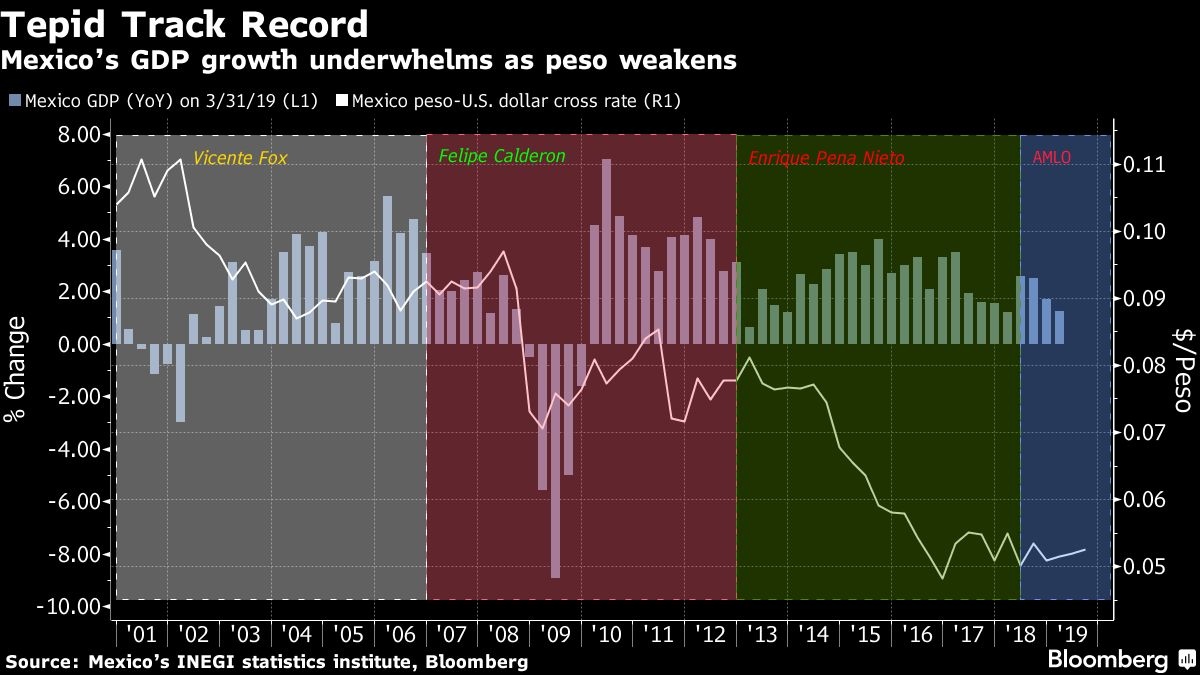

AMLO, as he’s known, has promised a revolution. And so far, 70 per cent of Mexicans approve of his job performance despite a faltering economy. So how is he doing?

On Monday, AMLO agreed to sit down with Bloomberg Editor-in-Chief John Micklethwait in his first interview with an international news outlet since becoming president in December. He boasted about his anti-corruption campaign, efforts to cut spending at the highest level of government, and minimum wage and social security payment increases.

Throughout the conversation, he darted between 19th and 20th century Mexican history, recounting bloody betrayals and conquests as if they had occurred yesterday. To match his austere rhetoric, he lives in an apartment within the palace, having opened the former presidential mansion to the public as a cultural center. His official vehicle, a simple white Volkswagen sedan, sits parked in the middle of a courtyard.

AMLO shrugs off criticism by measuring success and failure by different yardsticks.

His response to a slowing economy and possible recession? Defining success through economic growth is an outdated neoliberal concept that doesn’t take into account happiness and well-being. He wants a better distribution of wealth.

Rising crime? He’s focused on attacking the origins of the problem through better education, anti-poverty policies and targeted spending.

Credit downgrades? He says ratings companies are being too harsh. They rewarded previous administrations with higher scores for national oil company Pemex even as it racked up debt and production tumbled, while they’ve now begun to cut their ratings even though his administration is working hard to pay down debt, root out corruption and boost output.

He even puts a positive spin on U.S. President Donald Trump, who has threatened across-the-board tariffs, calling him an ally and saying he’s toned down his rhetoric against Mexican migrants.

The one area AMLO knows he can’t falter on is a balanced budget and keeping foreign investment in the economy. But asset managers are torn on what to make of him. Yes, he’s a fiscal conservative who is cutting wasteful spending and trying to root out corruption at all levels. But he’s also unpredictable: He canceled a US$13 billion airport and put key energy auctions for private oil companies on hold, though he says he paid off obligations from the airport saga and may restart the auctions.

His austerity, which markets normally love, seems ill-placed for growth. He says slashing spending is a matter of principle: “There can’t be a rich government with poor people.” But he has cut the budget more than any new government since the 1995 aftermath of the Tequila Crisis, even though the economy may have entered a mild recession in the second quarter.

AMLO’s slow, folksy speech contrasts with his ambitions to blow up the political and social structures that he blames for keeping Mexico from developing its potential and improving the lives of more than 120 million people.

“I have a dream that I want converted into reality,” he said. “That the day will arrive during my government when Mexicans won’t go to the U.S. for work because they’ll have work and they’ll be happy where they were born.”

For that to happen, he won’t be able to slow down anytime soon.