Dec 17, 2023

Chileans Again Vote on New Constitution, This Time a ‘Business Friendly’ One

, Bloomberg News

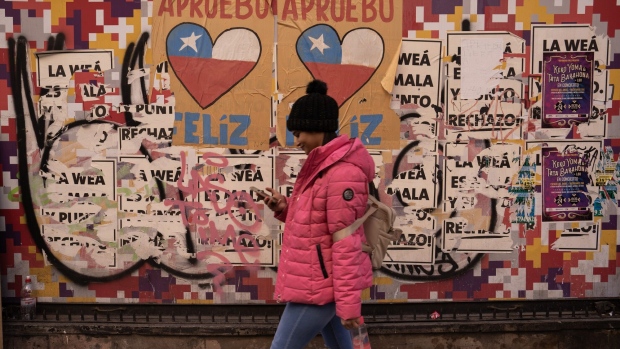

(Bloomberg) -- Chileans are heading to the polls in a second attempt to approve a new constitution and move past the period of political and economic uncertainty set off by the charter’s rewrite four years ago.

Sunday’s referendum asks voters if they’re in favor or against the text written by a right-leaning Constitutional Council to replace the current constitution, dating back to the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Voting centers will close at 6 p.m. local time in Santiago, and the result is expected to be published one to two hours after that.

The vote should be the culmination of a process that has roiled financial markets and stalled investment in the South American country. Polls indicate, however, that the document will be shot down — just like a previous and more left-leaning proposal was overwhelmingly rejected in September 2022. President Gabriel Boric has said there will not be a third attempt to rewrite the constitution if this one fails to pass.

Center-right and right-wing parties as well as some investment banks support the “business friendly” text, saying it will boost economic growth, control clandestine migration and reduce crime. Opponents say it would endanger hard-earned social victories such as abortion rights, set unrealistic goals on migration and improperly overstep in eliminating taxes.

Even as polls show that most Chileans want a new constitution, a survey from Cadem released Nov. 26 showed an 8 percentage-point advantage for those against this text.

The process of drafting a new charter came in response to social unrest in late 2019. Back then, an increase in subway fares evolved into broader demands to fight inequality, improve social services and reform the country’s political system. It also sparked riots and arson attacks.

Clear Rules

If those in favor of the new constitution score a surprising victory, local financial assets should rally and the Boric administration will be forced to tone down its reform agenda, according to Scotiabank.

Implementing the new charter would take between five to 10 years, Scotiabank economists Jorge Selaive, Anibal Alarcon and Waldo Riveras wrote in a research note.

Even though Boric has said the process ends with Sunday’s vote, a rejection of the current proposal wouldn’t put an end to all constitutional reform chatter. Political parties may try to drive changes to the charter through Congress or even back a new overhaul push further down the road, said Kenneth Bunker, a professor at Universidad San Sebastian in Santiago.

The debate will inevitably return before the next presidential election in 2025, Bunker said. “There can be some calm after the storm, but we will eventually come back to the same discussion.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.