May 9, 2023

Fewer Parents Are Vaccinating Their Kids. Here's Why They Might Not Have To.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- A few years ago, Robyn shared some concerns about vaccination with her two-year-old son’s pediatrician. She had heard about potential side effects and wanted to discuss them. Her doctor brushed it off.

Before that, Robyn had been open to vaccinating her son. Instead she was hardened against it.

“I was met with aggression instead of understanding of why I might be hesitant,” said Robyn, an Arizona mother who requested to use her first name only to protect her privacy. “That gave me even more reason to worry.”

The pandemic made more Americans question vaccines than ever before. But that distrust in Covid vaccines also had a spillover effect: it caused more parents to begin questioning routine childhood shots. Less than 80% of Americans believe childhood vaccines are important, compared to 93% before the pandemic, according to an April analysis from UNICEF that called waning childhood vaccinations a “red alert” situation.

And now, in states including Connecticut, West Virginia and Alabama, the concerns of parents like Robyn are fueling lawmakers’ attacks on the childhood vaccine mandates that have kept diseases like the measles at bay for decades.

Covid Stokes the Fire

The pandemic made people “more aware of how prevalent vaccine mandates are in their lives and the lives of their children,” said Matt Motta, an assistant professor at Boston University’s Department of Health Law, Policy and Management. “There was an opportunity for those attitudes to spill over and shape attitudes toward other vaccines.”

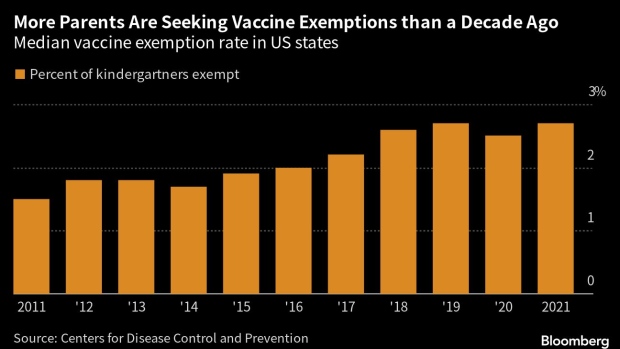

Childhood vaccination rates had already been slipping prior to the pandemic. But when the pandemic gave a surge of new energy to an already simmering suspicion of vaccines in America, it powered a dramatic drop in childhood shots. In January, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report showed that national kindergarten vaccination rates for some diseases fell by about 1 percentage point for the second year in a row. That percentage point may seem small, but it is enough to facilitate a resurgence of some diseases.

The national rate for the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine dropped to 93% among kindergarteners in the last school year – well below the 95% threshold necessary to keep measles from spreading. In some states, the numbers were far worse. In the same school year, Colorado’s kindergarten MMR vaccination rate dropped more than two percentage points, to 88%.

In the last year, the US has seen outbreaks of measles and even a case of long-eliminated polio. More outbreaks are likely to come.

Politicization of Vaccines

One major question is what is driving this decline. Some of it has been attributed to disruptions to routine health care caused by the pandemic – parents were afraid or discouraged from taking their kids to the doctor for routine care. But recent research has suggested changing attitudes towards vaccines have played a significant part.

In the wake of the pandemic, childhood vaccines are an increasingly partisan issue. One February study used the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting system — a government clearinghouse for vaccine side effects — to track the growing hesitancy toward childhood vaccines. Because VAERS is open to the public and reports are not verified before being posted, members of anti-vaccine groups often flood it with negative reports on vaccines. Motta, at Boston University, found that Republican-leaning states were more likely to see a surge of VAERS reports on the MMR vaccine, of which two doses are recommended before turning six years old.This, he says, shows how partisan sentiment toward Covid vaccines is now impacting attitudes toward childhood vaccines, too.

“Vaccines have become very heavily politicized,” said Motta. “One of the really important dividing lines that has emerged is the degree to which individuals ought to be able to express autonomy over their decisions to vaccinate or not vaccinate.”

And this partisanship is leading to further erosion of what may be the most important determinant of childhood vaccination rates: state policy.

School Mandates Under Attack

All states require children to get routine immunizations in order to attend school. But some states make it far easier for parents to opt out. States like New Jersey allow religious exemption from vaccines, and others like Pennsylvania also have philosophical exemptions. A handful of states, including New York, only allow exemptions in cases where it is medically necessary, and those states typically have childhood vaccination rates well above the national median.

But in the wake of the pandemic, childhood mandates are even under threat in states with typically strict laws. West Virginia, for example, doesn’t allow non-medical vaccine exemptions for students. But two bills introduced to the state legislature this year aimed to weaken the state’s mandates, removing Hepatitis B vaccine requirements and making immunization completely optional for private school students.

So far, at least, most recent efforts have not taken off. A Connecticut bill that fizzled, for example, tried to reinstate a religious exemption for immunization. A failed Alabama bill would have established the “My Child, My Choice Vaccination Act,” allowing immunization and testing exemptions for religious or personal reasons, even during an epidemic.

But some legislation has managed to be enacted. A 2021 Kentucky bill amended legislation to allow for exemptions for anyone “based on conscientiously held beliefs” and banned requiring vaccines for everyone during an epidemic. A Florida bill enacted the same year created a “Parents’ Bill of Rights,” which includes the right to exempt a child from immunizations. In total, 60 state laws were enacted limiting vaccination in some form, including childhood shots, from 2021 to May 2022, according to a report from the Network for Public Health Law.

Without vaccine mandates in schools, “you would see measles come roaring back more than it already has,” said Paul Offit, a physician and director of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia's vaccine education center. “We eliminated measles from this country in the year 2000. It came back because a critical percentage of parents chose not to vaccinate their children.”

Health-care providers may have the biggest sway in encouraging immunization. Having open, science-backed conversations about vaccines can reassure many parents hesitant about vaccinating their children, pediatricians said.“Nobody is hesitant about vaccines because they're trying to be a pain in the neck or anything like that,” said John Dunn, a pediatrician and medical director at Kaiser Permanente Washington. “They're hesitant because people that they trust, their inner social circle, have told them, ‘Look, you really need to look into this. You need to think about this.’”But lack of empathy can turn parents against vaccines for good.

Robyn, the Arizona mother, had been in the process of giving her oldest son his vaccines. After her doctor downplayed her concerns, she sought out her own answers online. Neither of her children have completed their vaccination schedules. She has no plan to change that.

“All I want to do is make the right choice for my kids,” she said. “But when you're met with anger and you're met with a lack of information and transparency, it gives me no reason to trust the healthcare industry as a whole.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.