Mar 29, 2022

Freeland to table budget April 7; deficits, rates, and housing issues

, BNN Bloomberg

Freeland has more room to spend in April budget thanks to higher oil

The countdown clock is officially ticking toward this year’s federal budget, with Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland announcing the budget will be tabled on April 7.

The rare April budget – coming after the beginning of the federal government’s fiscal year – is expected to lay out how the government views Canada’s path out of the ravages of the pandemic, unveil details on government support for a slate of issues including housing affordability, and provide a path back to more normalized spending after the feds unleashed torrents of cash to help the domestic economy.

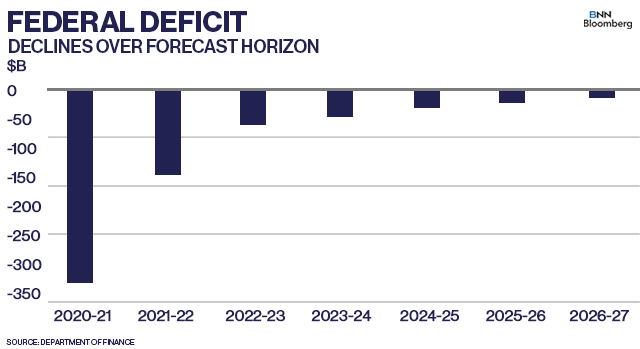

While the federal government has yet to outline a path back to balance, the trend from the fall fiscal update is clear: smaller deficits through the end of the forecast horizon, from a $58.4 billion deficit projection in fiscal 2022-23 to a modest $13.1 billion in fiscal 2026-27. What those projections don’t account for, however, is the interim measures announced since the December update which the Parliamentary Budget Officer projects could amount to $48.5 billion worth of additional spending through to 2025-26.

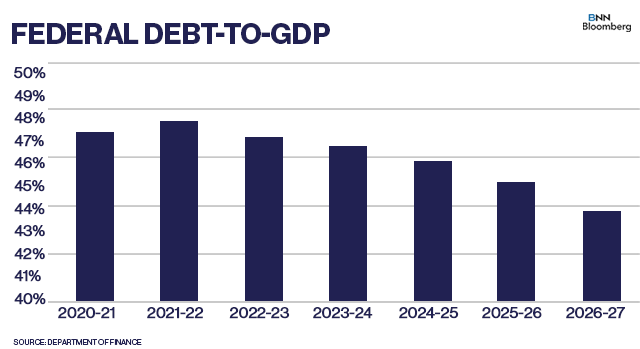

That spending path ties directly back to what is widely considered to be the federal government’s “fiscal anchor” through the current period of deficit spending: a declining debt-to-GDP ratio. Essentially, that anchor is a pledge by Ottawa that debt increases will not outpace overall gains in economic growth, thus keeping Canada on a sustainable fiscal path. According to the fall fiscal update, that figure was expected to peak at 48.0 per cent in fiscal 2021-22, declining steadily to 44 per cent by the end of the forecast horizon. There’s some optimistic wiggle-room in that projection with the key ratio falling to 42.1 per cent in 2026-27 under the Department of Finance’s faster recovery scenario.

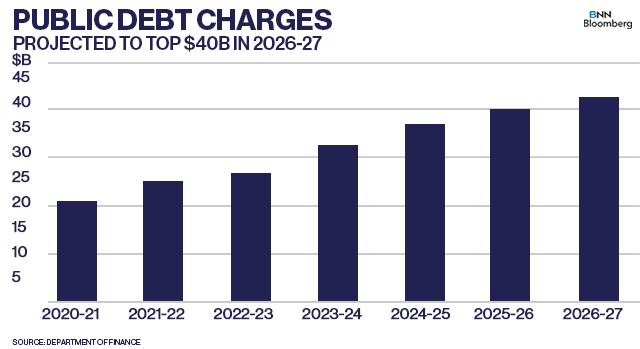

With the recent run-up in bond yields and the underlying Bank of Canada benchmark rate, those debts are about to get more expensive to service. The fall update pegged public debt charges – essentially the interest on existing debts and the cost of new borrowing – at $26 billion in fiscal 2022-23, rising to $40.9 billion in fiscal 2026-27 as interest rates rise. While that 2026-27 figure is roughly twice the cost of public debt charges in 2020-21, the feds are working off a low base – at a projected 1.3 per cent of GDP in 2026-27, those costs are well below the pre-financial crisis level of 2.1 per cent of GDP.

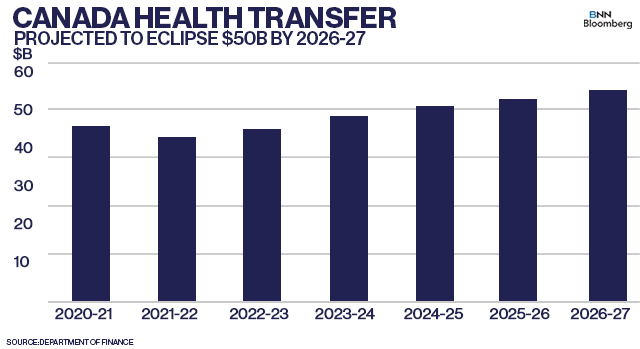

So where is the cash going? Beyond the obvious pandemic-era measures including business and income supports to Canadians rocked by public health closures, health transfers to the provinces remain one of the largest single-line expenditures for the federal government. A confluence of factors, notably Canada’s aging population, have set the path of those health transfers on a structural upward trajectory, with the fall fiscal update seeing transfers from Ottawa to the provinces rising from $45.2 billion in fiscal 2022-23 to $55.2 billion in 2026-27. That projection came before the Liberals struck a support agreement with the New Democratic Party, with strings attached to ensure a national pharmacare and dental care program are implemented. It remains to be seen if this year’s budget will have a full account of the costs involved in those programs.

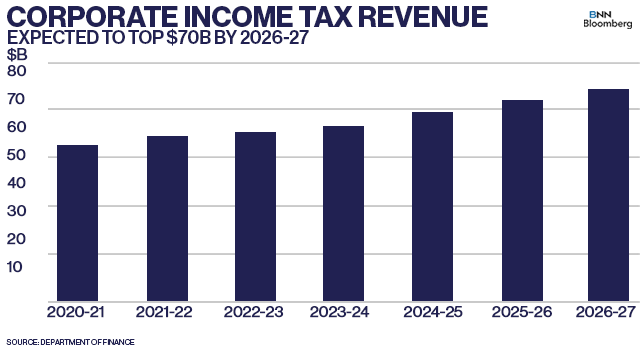

Part of that support deal with the NDP included implementing a Liberal campaign promise to help bolster the federal coffers by hiking taxes on the big banks and insurers, the initial announcement of which came much to the chagrin of industry groups like the Canadian Bankers Association. When announced, the Liberals projected that surtax – an increase to 18 per cent from 15 per cent on profits over $1-billion – would raise about $11 billion over the course of five years. As of the fall fiscal update, the feds already saw a steady increase in corporate tax revenue, rising to $73.7 billion in fiscal 2026-27 from the $58.4 billion in 2022-23. All told, corporate tax revenue is still dwarfed by personal income tax proceeds, with Ottawa projecting it will rake in $232.8 billion worth of income tax in 2026-27.

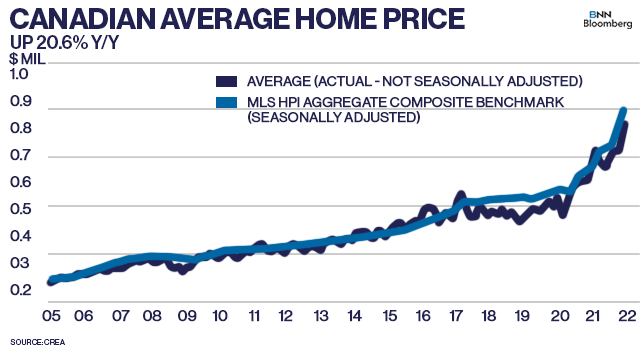

Finally housing affordability – or a lack thereof – is expected to be a central plank of this year’s budget as prices spiral out of control in Canada largest urban centres and in secondary communities as some Canadians who were able to work from home moved further afield during the pandemic. Against that backdrop, the average non-seasonally adjusted home price hit a record $816,720 in February, up 20.6 per cent from a year ago, according to the Canadian Real Estate Association (CREA). Liberal housing pledges during the election campaign totaled about $17 billion in spending over five years, as they set a target to build or repair 1.4 million homes over four years, among other measures. There are some concerns that new measures could in fact fuel housing demand, including plans to double the Home Buyers Tax Credit and a 25 per cent reduction in CMHC mortgage insurance costs, which could harm the Bank of Canada’s efforts to stamp out some vulnerabilities stemming from the housing market.