Jun 6, 2020

Guardians of the world economy stagger from rescue to recovery

, Bloomberg News

Bank of Canada believes COVID-19 impact on economy may have peaked

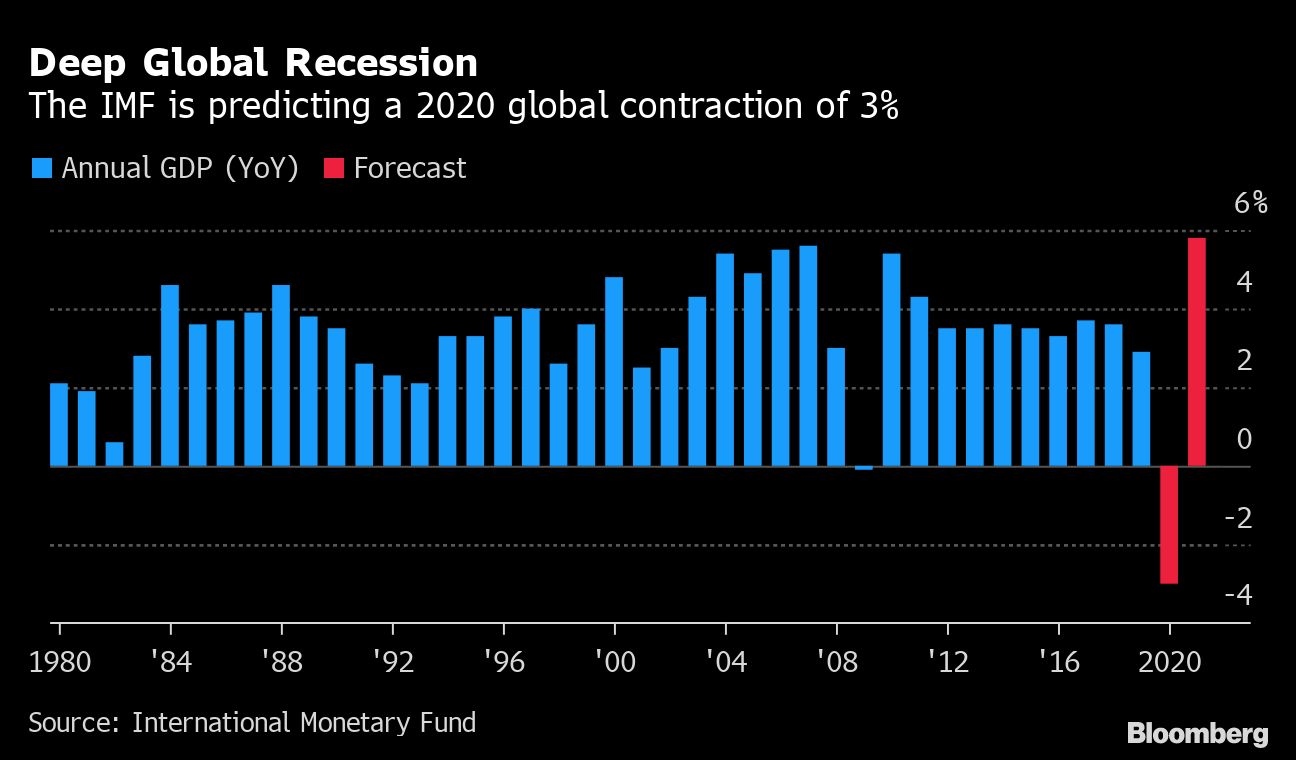

The world’s governments and central banks are shifting from rescue to recovery mode as the deepest slump since the Great Depression shows signs of bottoming out.

After rolling out trillions of dollars worth of measures to prevent their economies and markets from collapsing, they are now doubling down with even more spending to backstop a recovery as coronavirus lockdowns ease. In what counts for good news these days, Bloomberg Economics’ global GDP growth tracker showed economies contracted at an annualized rate of 2.3 per cent in May, less than the 4.8-per-cent slump in April.

“Policy-makers are moving from triage to recovery,” said Deutsche Bank Securities Chief Economist Torsten Slok. “They are realizing that more fiscal support will be needed to households and small businesses to prevent this liquidity crisis from turning into a solvency crisis.”

The new wave of stimulus has both governments and central banks moving in sync to continue flooding lenders, markets and companies with cheap credit at an unprecedented pace.

The European Central Bank last week expanded its asset purchases by 600 billion euros (US$677 billion) to 1.35 trillion euros, and extended them until at least the end of June 2021. And Germany’s government agreed another 130 billion-euro fiscal stimulus push and said it will back a proposed new 750 billion-euro European Union recovery fund.

“Action had to be taken,” ECB President Christine Lagarde said in a press conference.

It’s a similar story in Asia.

Japan is planning another US$1.1 trillion worth of spending in its biggest splurge yet and the central bank in May called an emergency meeting to roll out 30 trillion yen (US$274 billion) of loan support for small businesses.

China last week unveiled another 3.6 trillion yuan (US$508 billion) in spending and South Korea’s 76 trillion won (US$63 billion) ‘New Deal’ fiscal package is its largest to date.

In the U.S., lawmakers continue to debate extra fiscal stimulus and the Federal Reserve, which meets on June 10, has just launched a new Main Street Lending Program, the latest in trillions of support it has already poured into the economy and markets.

While the Fed is unlikely to signal any moves when its officials gather this week, many economists expect it to harden its commitment to easy monetary policy later in the year and perhaps even start pursing a Japan-style campaign to control long-term borrowing rates.

The latest U.S. jobs numbers give some hope that the stimulus unleashed so far is beginning to kick in. A record 2.5 million workers were added by employers during May while unemployment declined to 13.3 per cent, wrong footing economists who had forecast widespread job losses.

To be sure, there’s far from consensus that the latest wave of support will be enough to get growth back to where it was at the start of the year. Some of the steps being taken are merely to replace existing policies as they start to expire.

“It seems clear already approved packages are perceived to be not enough,” said Alicia Garcia Herrero, chief Asia-Pacific economist at Natixis SA.

There are other concerns that monetary policy can only do so much to revive growth before it loses its potency.

“How does the Fed actually get money to millions and millions of households and small businesses, that is difficult to do operationally,” former New York Federal Reserve Bank President William Dudley told Bloomberg Television.

“It’s much easier to intervene in the capital markets where the Fed can rely on counterparties, primary dealers and others,” Dudley said. “It is much more difficult to lend one by one to millions of different entities.”

Another risk is a return to austerity, even if it seems unlikely now. JPMorgan recently predicted a fiscal thrust of 3.3 per cent of GDP this year and 1.5 per cent drag next year.

U.S. senators have put the brakes on a US$3-trillion fiscal package that was approved by lower house lawmakers. China’s government has ruled out a return to the kind of large scale stimulus it rolled out after the global financial crisis, preferring to keep a lid on rising debt.

Still, because the crisis meant economies were forced into shutdown, much of the emergency response so far has been less about driving growth and more about avoiding total collapse. It’s that dynamic which is leaving governments with little option but to borrow harder.

“We shouldn’t look at the positive immediate growth impact of the opening up process as being the rate of growth that may last,” said David Mann, chief economist for Standard Chartered Plc.

Creating jobs will be mission critical to cementing any upswing. That will need support for firms to retrain employees, incentives to hire older workers and for governments to continue with wage subsidies. More than one in six people have stopped working since the onset of the crisis, according to the International Labour Organization, which in April estimated more than 1 billion workers were at high risk of a pay cut or losing their job.

“A faster job market recovery will speed up the economic healing and reduce the risk from widening income inequality and social stress,” said Chua Hak Bin, senior economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research Pte.

Ultimately, the rescue of economies will go well beyond quantitative solutions and into the realm of story telling too, as policy makers will need to inject confidence back into wary consumers and executives, said Stephen Jen, who runs hedge fund and advisory firm Eurizon SLJ Capital in London.

“Human psychology is the same and is now as important as the mechanics of delivering the fiscal stimuli themselves,” he said.