May 17, 2020

McCreath: Brace for 'really ugly' earnings and election risk

Safety sectors in the markets: McCreath

As I write these thoughts on the markets, the S&P 500 has just bounced off the low end of its latest 2,800-2,950 range while the U.S. dollar, gold and oil continue to grind higher.

There’s little question that financial markets have stabilized and equities have recovered half their losses thanks to the aggressive and gargantuan monetary support of the world’s central banks.

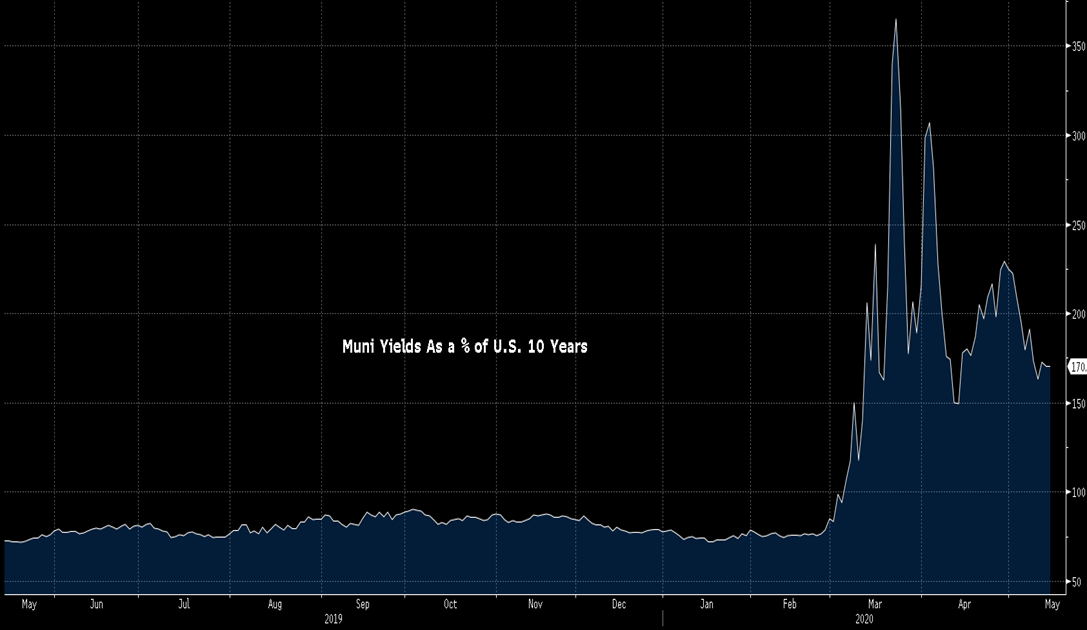

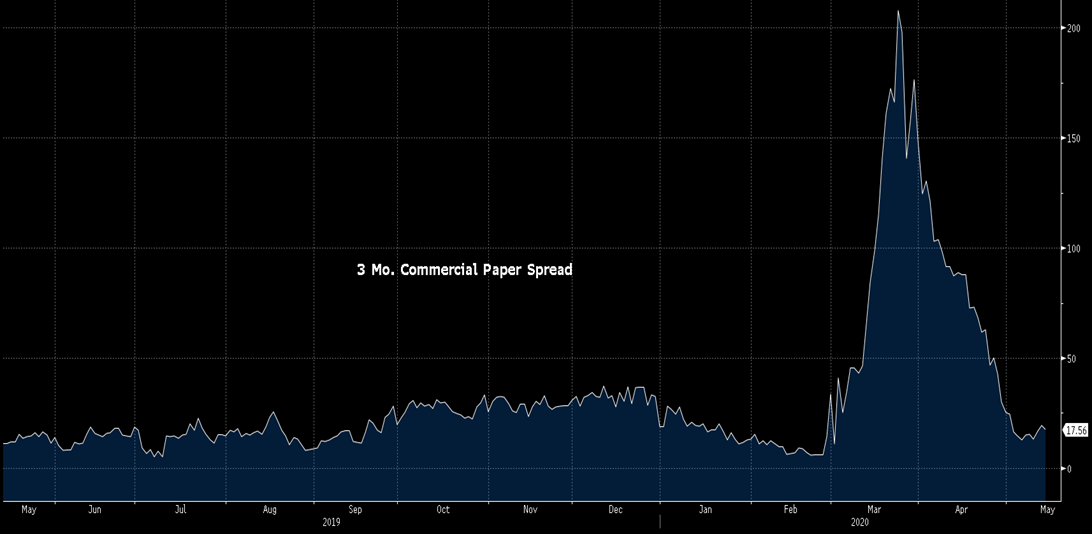

Central bank actions, specifically by the U.S. Federal Reserve, have been exceptionally effective at ensuring that the short-term seizure in the plumbing of financial markets that we saw in late February and early March was reversed and re-instilled confidence among players in the financial markets. That’s pretty obvious from reviewing the spreads of agency mortgage-backed securities, commercial paper, municipal bonds and U.S./Euro swap rates in the next four graphs. Well done, Mr. Powell.

Most importantly, the next four graphs suggest the plumbing of markets has been fixed.

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg

In forming a view of where equities go from here, I believe we’ve moved into a hiatus period for any substantively incremental monetary stimulus or fiscal accommodation.

Sure we could get more of both, but I just think it won’t be coming in the near term. Consequently, it’s up to progress against COVID-19, the pace of the re-opening of the economy, and presumably corporate outlooks to determine whether equities pull back, bide their time within their most recent range, or keep grinding higher.

Let’s review the status of each of these variables.

So far, so good with respect to arresting the explosive growth in COVID-19 cases. The growth in new case counts in western Europe, ex-Italy, has stabilized, albeit at still somewhat elevated levels. In the U.S., while there’s definitely several hot spots, the good news is the trajectory of the seven-day average, excluding the state of New York.

Fingers crossed these improvements continue but two points merit attention.

First, we all know that the pace of re-opening is the epitome of a fine balance. Second, as the absolute number of cases is the highest it has been to date, the imperative of testing even more people becomes of paramount importance. Let’s hope all governments adhere to that requirement.

As for the state of the economy, I’d argue the economic data we’re seeing right now is irrelevant, whether it was last week’s U.S. retail sales miss or better than expected industrial production data from China. That’s because the data that we’ll get during the next two months is almost guaranteed to be universally worse.

The question is what the eventual recovery in U.S. GDP is going to look like.

As recently as last week, it appeared that consensus, or what may be priced into equities, thought the U.S. economy could be back at 70 per cent of its capacity by Labour Day. That strikes me as being optimistic, and of course that’s why I believe markets will wait for supporting evidence before exhibiting any grind higher. Let’s face it, it’s anybody’s guess.

As for earnings, 91.9 per cent of the S&P 500’s market cap has reported first-quarter results. Year-over-year rates of growth in revenue and earnings have been +0.6 per cent and -13.4 per cent, respectively (-6.2 per cent for profits if financials are excluded).

However, similar to GDP, it’s the second quarter that’s going to be really ugly, while the pace of the recovery will determine whether 2020 earnings per share for the S&P 500 will remain near the US$130-$140 consensus or move lower. We should know the answer by mid-July.

I’m in the camp that once growth normalizes, say 12 months from now, that U.S. GDP growth will remain tepid, say in the range of 1.8 to two per cent, with a lower number here at home in Canada. Such an outcome would support a continuation in the long-term trend of slowing corporate revenue growth.

As for earnings, sure rates are even lower today, but what’s the outlook for corporate taxes? Hard to believe they don’t go up. And what about labour costs? Since part of U.S. President Donald Trump’s current fiscal accommodation has dislocated workers getting paid US$25 per hour, it’s tough to argue against a minimum wage of at least US$15 per hour.

If I’m correct and economic growth doesn’t pick up during the next 18 months, can equity leadership change? Sure, as the economy re-opens I suspect we’ll see a tactical shift toward value and cyclical stocks and a back-up in long-term bond yields due to a belief that renewed inflation is around the corner.

However, once growth normalizes in a year or so, as I stated above, I believe neither growth nor inflation will accelerate. Of course, such an event doesn’t speak well to the ultimate upside in stocks as valuations on growth stocks aren’t exactly cheap.

That’s the cup half-empty argument, in contrast to others such as JP Morgan Quant Strategist Marko Kolvanic, who believes central bank liquidity will further expand valuations. Such a pitch is entirely possible; but, as I’ve told many clients over the past several weeks, I’m not the guy to get really long the market because I believe the price to earnings multiple is going to expand from the current 21X to 24X.

At Forge First, we’re value investors focused on buying companies that generate free cash flow, ideally offering free cash flow yields of at least eight to 12 per cent, while shorting companies that either burn cash or require continued access to financial markets to finance their business.

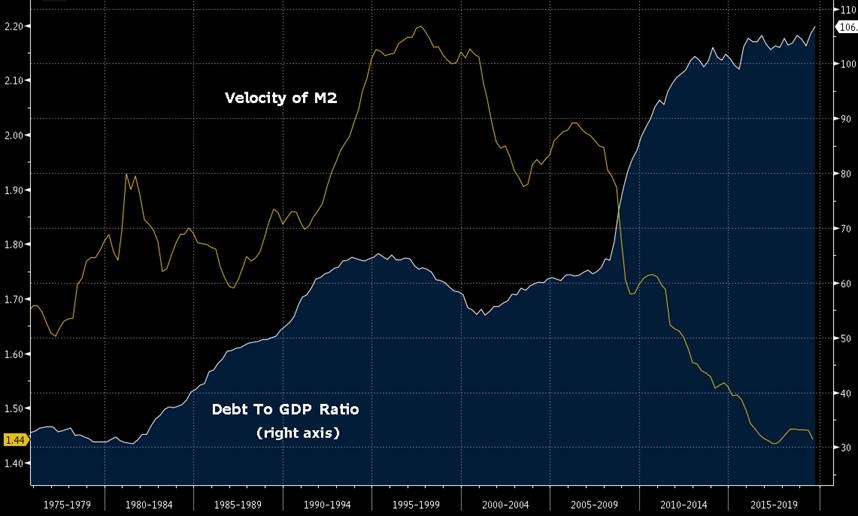

For economic growth to accelerate beyond my expectations, and for inflation to pick up, the velocity of money has to get up off the bottom.

As shown by the orange line in the 45-year graph below, this key variable has been on a steady course downward since 1995. In looking back at the experience of 2008, both government spending and the growth in money supply picked up markedly. However, post-crisis, the marked tightening in fiscal policy is likely one reason why inflation didn’t accelerate. This cycle, the apparent limitless amount of stimulus and accommodation has rekindled fears of inflation. Yet for at least the next couple of years I don’t buy that pitch given the disinflationary trends in the economy and the growing tendency to hoard cash.

Velocity must turn if the U.S. is to experience a return to growth and inflation

Source: Bloomberg

And while the topic of inflation is receiving much attention, the graph below shows that it’s sure not getting priced into the financial markets. What this graph suggests is that in five years, the rate of inflation for the subsequent five years will only average 1.38 per cent.

U.S. five-year forward breakeven: Proxy for inflation in the next five years, starting five years from now

Source: Bloomberg

It’s these concerns that inflation won’t pick up that has fostered recent dialogue about the Fed moving toward negative interest rate policy (NIRP). While last week’s remarks by U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell appeared to put an end to the discussion of NIRP, markets (be it just technical factors or otherwise) are still pricing in such a possibility. I’m totally against negative interest rates. This policy hasn’t worked anywhere else plus it could materially disrupt the perceived house of safety for cash: money markets.

Taxable U.S. money market fund assets now exceed US$4.6 trillion

Source: Bloomberg

One other item markets are going to begin to consider over the summer is the U.S. Presidential election. While November 3 seems like it is a long way away, it’s wrong not to consider what a Democratic sweep could mean for financial markets. Presumptive Democratic Nominee Joe Biden has stated that he’d raise corporate taxes and it would be likely that many of Trump’s actions to slash regulation and environmental protection would be reversed once again.

Last but not least, the other day I read a report published by the C.D. Howe Institute about Canada’s fiscal position. (Here’s the link to the report). It is an understatement to say that it’s a sobering read. The baseline scenario projects deficits of $73 billion next year, and more than $50 billion per year from 2022-23 to 2024-25 such that federal debt reaches 49.1 per cent of GDP by 2025. Total federal debt appears poised to eventually exceed $1 trillion. Combined with huge provincial levels of debt, this financial burden will leave Canada in a real conundrum. The highest marginal tax rate in many provinces is already over 50 per cent. It’s unfathomable to contemplate even higher tax rates than we have today, but do you really think Ottawa will cut services? Unfortunately, don’t hold your breath.