Apr 4, 2024

The 2024 US Election Is Already Being Fought in the Courts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- For the 2024 election, Arizona officials didn’t want a repeat of two years ago, when masked and armed people intimidated voters. So the state barred groups from monitoring drop boxes and polling locations.

Immediately, conservative groups filed lawsuits in the Democratic-led swing state, arguing the change violated free speech rights.

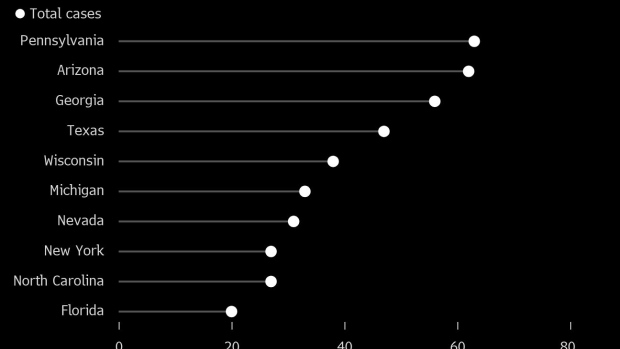

Political groups — some backed by anonymous donors — are launching so many lawsuits over voting rules this year, observers expect that they could approach the record set during the rancorous 2020 election amid Covid and bogus claims of fraud. The Democratic and Republican parties collectively have raised about $41.3 million to spend on such court fights since last year. And nonprofits, including some so-called dark money groups, have likely raised as much as hundreds of millions more.

“Voters deserve to know they have a system where it’s easy to vote and hard to cheat,” said Scot Mussi, president of the Arizona Free Enterprise Club, which is suing to strike down Arizona’s new rules including those barring the monitoring of polls and drop boxes by outside groups.

After the last presidential election, which Donald Trump falsely claimed he won, spurring some of his supporters to riot in the US Capitol, states enacted a number of measures to improve voting procedures and reduce the risk of interference, such as extended polling hours.

Never miss an episode. Follow the Big Take podcast on iHeart, Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you listen. Read the transcript.

With Trump now headed for a rematch with President Joe Biden, political groups are challenging and defending these moves as well as plumbing for legal minutiae, pushing the courts to the center of the election process. Indeed, the US Supreme Court in March rejected a Colorado effort to boot Trump off the ballot.

While some lawsuits attempt to address legitimate concerns, others serve as political strategies, said Martha Kropf, a professor of political science at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.

“Close elections mean you’re going to fight to get every extra vote you can,” she said.

With the presidential race poised to come down to seven pivotal states, Arizona, Michigan and Pennsylvania are already heated battlegrounds for litigation. Judges, not voters, may determine the election results, fear some experts and activists.

Arizona, which is also home to a tight US Senate race, hopes to head off the conspiracy theories that sprung up four years ago. Democratic officials said widespread voter intimidation could result if the Arizona Free Enterprise Club’s most recent lawsuit prevails.

As is the case with other court fights across the country, the limited-government advocacy group works with influential partners, including America First Legal, led by former Trump White House adviser Stephen Miller, and Restoring Integrity and Trust in Elections, a nonprofit backed by Trump allies including billionaire Steve Wynn.

Such partnerships lead to more influence. As it takes on more cases, Mussi’s group has seen its revenue jump three times to over $3.4 million in 2022 from the year before, showing how it has quickly become a power player in Arizona.

“There’s a lot of good work being done on the conservative side of the spectrum these days to defend elections,” said Derek Lyons, a former Trump adviser who now leads Restoring Integrity and Trust in Elections, which has funded and supported more than 30 cases in 17 states.

Prominent Democratic lawyer Marc Elias characterized some of these newly formed ventures as “vigilante.” He and his firm are filing dozens of lawsuits against voting restrictions across the country, often partnering with grassroots groups in swing states.

"New Republican election vigilante groups are emerging to launch mass voter challenges against unsuspecting voters," Elias said in a social media post this week.

https://t.co/2V6JKqrwPj

— Marc E. Elias (@marceelias) April 3, 2024Indeed, fighting battles over election rules big to arcane is a booming business for such groups and lawyers. Political parties’ legal expenses have skyrocketed to $154 million in 2022 from around $5 million in 2003, according to data compiled by Derek Muller, a law professor at the University of Notre Dame. And nonprofits, including charitable organizations and dark-money advocacy groups, are increasingly filing and financing election-related lawsuits. They’re not legally required to identify their backers.

“You’ve got a lot of organizations that don’t have to disclose their donors, they don’t have to disclose how they’re spending their money,” said Muller. “There’s an effort to influence elections through the litigation process without the same transparency we see over on the campaign side.”

Challenging every aspect of the electoral process as a political tool started in earnest after the Supreme Court effectively decided the 2000 presidential contest in favor of George W. Bush over Al Gore in Florida’s recount fight. Election litigation has since tripled, according to research by Rick Hasen, a professor of law and political science at University of California, Los Angeles. Lawsuits span disputes about signatures on absentee ballots to all manners of allegations of illegality.

During the 2020 election, public health issues surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic, in addition to the unfounded claims of fraud perpetuated by Trump and his allies, led to a record number of election lawsuits.

Congress played a role in the increase, too: In 2014, it allowed donors to bankroll parties’ legal expenses. The contributions, which currently can be made in amounts up to $123,600, give the parties ample funding to fight in court.

Groups aligned with Democrats say they’re trying to stop voter suppression. Most lawsuits from Republican-leaning allies are aimed at creating more election oversight, including voter identification rules and tighter restrictions on who can vote.

Unsettled Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania has the most unsettled questions around its electoral procedures, according to Muller, and both sides of the ideological divide have launched legal challenges since January alone.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, for one, challenged York County’s restrictions on nonpartisan election observers. And Voter Reference Foundation, a group with ties to GOP megadonor and billionaire Richard Uihlein, sued the state for declining to publish voter data on the internet.

“There’s a focus on the really granular things that maybe a couple of years ago weren’t litigated to the same degree that they are now,” said Adam Sopko, staff attorney with the Wisconsin Law School’s State Democracy Research Initiative.

(Adds the number of cases that Restoring Integrity and Trust in Elections supported in 13th paragraph.)

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.