Mar 3, 2022

The Shock of the Old, the Promise of the New

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

I draft this column not quite a week into the biggest war in Europe in eight decades. I was a student of international relations and energy policy in my earlier years, but I am by no means a foreign policy expert today. I am, however, an observer of today’s energy landscape and the networks that connect, and sometimes bind, countries and molecules.

Watching Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I am sure we are all struck by the newness of it playing out in near-real time on social media. At the same time, its mechanics are sadly familiar. It is kinetic warfare, in military parlance, with vehicles, tactics, engagements and shortcomings that would be familiar to any military historian. It reminds me of David Edgerton’s The Shock of the Old — not just featuring old technology of warfare and industry, but inextricably dependent on both.

It is in that dependency that I can offer some context and ideas about this war and its implications for energy and climate. It hardly needs saying, but when one of the world’s biggest producers and exporters of fossil fuels becomes almost instantly cut off from major trade, the interdependencies Russia has created become immediately apparent.

This war has pulled a number of policies into play that until this moment were exceedingly unlikely, even outlandish. Germany, Europe’s biggest importer of Russian gas, now plans to build liquefied natural gas import terminals, significantly increase its renewable power commitments, mandate a minimum level of gas storage at the end of each season, and perhaps even extend the life of its nuclear fleet.

It has also forced the hand of major companies for which Russian commitments could have proven a challenge for long-term strategy. Both European and U.S. big oil supermajors are breaking their substantial bonds with Russian oil and gas production, which will result in significant financial impairments and write-downs. But those breaks will also create the necessity to generate free cash flow from something else.The conflict has highlighted a number of medium-to-long-term solutions for energy security, particularly in Europe: greater electrification of transport (along with de-carbonization of power generation, of course), and especially electrifying heating and cooling loads. I quite like the phrase “Heat Pumps for Peace and Freedom,” for instance — an echo of World War Two-style mobilization of resources to materially change our dependence on fuels.

Other fixes for oil supply, in particular, may not be as forthcoming. U.S. shale oil producers’ main priority remains fortifying their balance sheets, not pumping with abandon. That strategy could bend, and it might break open — but it will be done deliberately, and the bigger the company, the more cautious it now is.

This war, and the energy markets turmoil it creates, should also make the case for three key levers of deep de-carbonization all the more compelling. Wind power and solar power address the world’s demand for fuel used in our grids; electric vehicles address the fuels used on our roads. These technologies have benefited from decades of learning effects, increasing efficiencies, and decreasing costs — only now to face supply chain, commodity, and interest rate headwinds.

I want to look further ahead, as well, by looking further back. At the time of the first oil price shock in the 1970s, many major economies were highly reliant upon oil as a primary energy source. Less than 15 years later, as Nikos Tsafos of the Center for Strategic and International Studies notes, those economies had significantly reduced their reliance on oil.

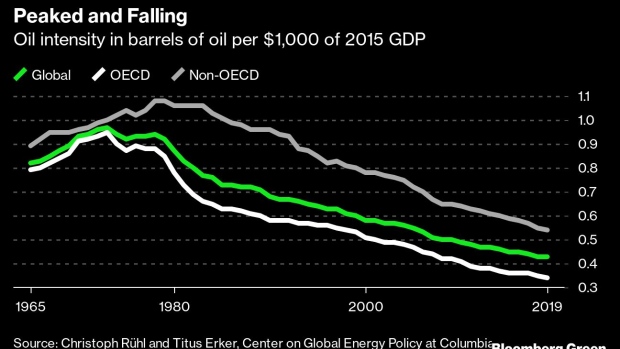

Not only that, the world also moved quickly to reduce what had until that point been an increasing proportional relationship between oil consumption and global GDP. In a 2021 research paper, Christof Rühl and Titus Erker of the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University highlight that the global oil intensity of GDP, and the OECD’s oil intensity of GDP OECD, both peaked in 1973. For the rest of the world, that peak came only five years later in 1978.

That same urgency that led to this peak must be now channeled, now, not just into substituting wind power for gas, and a batteries and motors for internal combustion engines, but into the most substantial changes possible. That is, a deep decarbonization of everything — industrial metals production, chemicals production, fertilizer production, heating and cooling, long-distance and heavy transportation in the air and at sea. Everything.

That urgency must also go into a thoughtful and deliberate maintenance of resilience in our existing energy system. That means, for some time to come, greater oil and gas storage capability, redundancy in sources, and making reliability of supply (and with it insofar as possible, stability of prices) an economy-wide imperative. One conclusion of BloombergNEF’s annual New Energy Outlook is that deep decarbonization will result in short-term mismatches of energy supply and energy demand. Smoothing those mismatches will be massively challenging but has never been more urgent.

And of course, there is the climate itself. The latest report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns clearly that the window for us to limit the most destructive impacts of climate change is “rapidly closing.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a shock of the old. The connections between energy, climate, trade, politics and conflict have never been more apparent. What is new today, and hopefully promising, is the possibility to build a positively connected, more resilient, and decarbonized future.Nathaniel Bullard is BloombergNEF's Chief Content Officer.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.