Jun 25, 2020

Wirecard Shows Life at Hedge Funds can be Agony

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You know the German finance world has been shaken when even the president of BaFin, the country’s conservative stock market regulator, showers praise on hedge funds. Apologizing for Germany’s failure to prevent a massive accounting fraud at electronic-payments group Wirecard AG, Felix Hufeld paid belated tribute this week to those “journalists, analysts or yes, let it be short sellers, who have been digging out inconsistencies persistently and rigorously.”

Hedge fund short sellers who suspect a company is overvalued borrow its shares from other investors and sell them. If the stock price falls, they repurchase the shares and return them to their original owner — pocketing the difference between the inflated price at which they sold them and the cheap price at which they repurchased them.

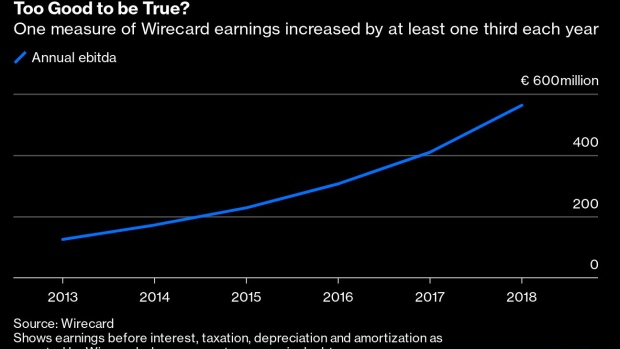

Things rarely pan out smoothly when doing this, but the tribulations of shorting Wirecard, which started filing for insolvency on Thursday, belong in a category of their own. With an army of credulous equity analysts and fund managers cheering the stock higher, and an auditor happy to sign off the accounts, Wirecard was a mightily difficult beast for the shorts to slay. Despite all kinds of warning signs, investors “gave the company the benefit of the doubt over and over and over again,” Jim Chanos, the founder of hedge fund Kynikos Associates — who helped expose Enron’s accounting crimes — told Bloomberg Television.

Some will say that hedge funds don’t deserve our appreciation because they profit from misfortune — and they’re not always justified in whom they target. Those who held on doggedly to their Wirecard short positions, or who showed up at the end when it couldn’t hide its accounting tricks any longer, netted billions of euros of profits. When Wirecard admitted this week that four-fifths of its net cash probably didn’t exist, Coatue Management, TCI Fund Management, Greenvale Capital and Darsana Capital Partners were among the funds with the largest short positions.

But, believe it or not, for many short sellers it’s not only about the money. They perform an important though rarely acknowledged function in rooting out corporate malfeasance through countless hours of detective work, often at great expense. As with Wirecard, they’re sometimes happy to share their concerns with regulators. “Short selling can be a valuable indicator of fraud and misrepresentation,” Fahmi Quadir of Safkhet Capital, a prominent Wirecard short, wrote in a letter to BaFin last year after the regulator took the rare step of banning the shorting of the German company’s stock.

Sadly, Wirecard isn’t the first example of regulators, directors and auditors failing to listen. Instead of showing any appreciation for these Woodwards and Bernsteins of the financial world, short sellers are maligned. German prosecutors looking at Wirecard focused their efforts on investigating alleged market manipulation by short sellers, rather than the fraud its employees were busy perpetuating. The company described a letter from TCI Management’s Chris Hohn, calling for Chief Executive Officer Markus Braun’s ouster, as “the purely tactical maneuver of a short seller.” In other words: Please investors, ignore anything Hohn says, because he just wants the share price to go down.

A decade-long bull market, characterized by large passive investment flows, fervent retail shareholders and a political environment where facts no longer matter, has made shorting a pretty unrewarding activity. Elon Musk regularly heaps social media scorn on those who doubt Tesla Inc., but that’s nothing compared to the emotional and financial trauma of shorting Wirecard.

In 2016, when a then anonymous outfit Zatarra Research published a critical dossier on Wirecard, almost a quarter of the company’s shares had been borrowed by short sellers, according to IHS Markit data. Mark Hiley, whose research firm The Analyst published the first of 43 notes querying Wirecard’s accounting in 2014, says hedge fund clients who shorted the stock at that time “got burnt” when the stock surged.

Some decided Wirecard was just “too hard to short,” Hiley told me, because of the hype around fintech stocks and because they didn’t have faith that regulators and auditors would step in. “Now we feel vindicated but over the past six years we were continually told we were wrong by the market — it caused a lot of stress.”

A similar thing happened in early 2019, when the Financial Times exposed financial irregularities in Wirecard’s Singapore office. The company made light of the report and sought to boost its credibility by announcing an investment from SoftBank. The stock rebounded and the hedge funds’ misery was compounded just hours later when Ernst & Young signed off on Wirecard’s 2018 accounts. It shouldn’t have done so, given what we now know about Wirecard’s fake cash.

No wonder John Hempton, co-founder of Bronte Capital Management, who shorted Wirecard for a decade, wishes he’d never heard of the company, which became the biggest loser in the history of his firm.

Worse than Wirecard’s slipperiness was its aggressive pursuit of what it alleged was a conspiracy between FT journalists and short sellers to undermine the company. Social-media trolls leapt to Wirecard’s defense and hedge funds that shorted the company became the target of a sophisticated hacking operation, according to an investigation by research outfit Citizen Lab. Some individuals were “targeted almost daily for months” by phishing attacks, its report said. One of those people was Matthew Earl, co-author of the 2016 Zatarra dossier, who says his house was put under surveillance. Citizen Lab didn’t claim Wirecard orchestrated the hacking, and Wirecard denied doing so. However, Wirecard has admitted hiring private investigators in the past.

Even now, some short sellers are reluctant to speak on the record. “It was by far the most backlash we’ve ever had,” one hedge fund employee told me. “There were people with hundreds of millions of wealth dependent on the fraud remaining concealed.”

Maybe investors will now have a new appreciation of the work short sellers do in probing corporate accounts, and will question how a business is really generating profit. Chanos says there’s another silver lining: He expects to use Wirecard as a case study in the class he teaches on the history of financial fraud.Elaine He contributed a chart.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.