Apr 7, 2022

A $430 Billion Habit Got Japan's Central Bank Hooked on ETFs

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In most of the world, exchange-traded funds are simply tools that allow investors to track a certain set of stocks. In Japan, they’ve been saddled with everything from propping up the market and boosting inflation, to accelerating economic growth, improving corporate governance and even encouraging gender equality.

Such wide-ranging goals have led the Japanese central bank to amass a whopping 80% of the country’s ETFs—equivalent to about 7% of its $6 trillion stock market—in less than a decade. That’s far further than any other central bank in the world has gone in trying to prime its economy via equities purchases. The Bank of Japan has also outpaced peers with its $3.7 trillion in net bond purchases.

But nine years and few hundred billions of dollars worth of ETF purchases later, the most striking consequence of the world’s boldest monetary experiment is this: The BOJ is stuck with a vast portfolio it might not be able to get rid of.

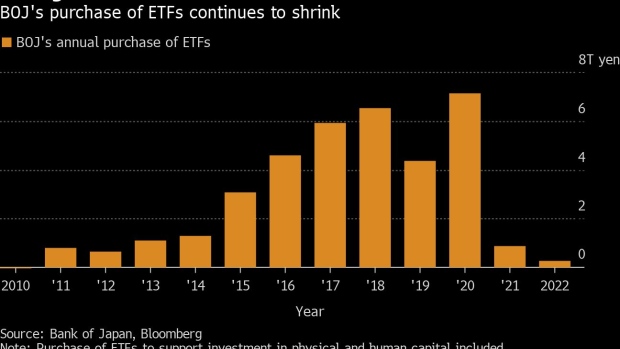

One year ago, the central bank effectively halted its ETF purchases—the first clear step towards winding down this part of its extraordinary intervention that critics said had distorted the market and made it the largest owner of the nation’s stocks. The move is in sharp contrast with the BOJ’s seemingly insatiable appetite for government bonds. Just last week, the central bank made global headlines when it launched a four-day long unlimited buying spree to stave off a global debt rout and keep yields under control.

The slow retirement of its ETF-buying program has been a quieter affair. Governor Haruhiko Kuroda remains tight-lipped about an exit plan as he prepares to step down in 2023; the tricky task of offloading the BOJ’s position without sparking a major selloff in stocks will now fall to his successor. Doing so may take decades, if not generations. Already the biggest stock market intervention in central bank history, it has prompted criticism that it has failed to live up to the hype. CLSA Securities summed up the sentiment in a Dec. 2020 note: “Thanks for nothing.”

How the BOJ got here is a cautionary tale for policymakers and investors everywhere about how far a central bank should intervene in capital markets and the perils of artificially propping up a market for so long that it becomes hard to see a way out.

“They cannot sell now. Shares will fall for sure,” said Tetsuo Seshimo, a portfolio manager at Saison Asset Management Co. “The negative impact would be pretty huge.”

Japan’s economy was a global outlier in 2013, when the central bank set about reversing 15 years of deflation with its unprecedented asset-buying scheme. And it remains an outlier today, for all that the bank’s spending has done to weaken the yen, boost corporate profits and lower unemployment.

Demand-driven inflation is still too weak to keep prices rising at the BOJ’s desired pace, and is well below rates in other major economies. So while global peers like Jerome Powell ramp up their fight to rein in inflation, Kuroda remains wedded to stimulus.

“The likelihood of other central banks following the BOJ’s lead on ETFs is extremely low,” said Kazuo Momma, who served as head of monetary policy at the BOJ before leaving the bank in 2016. “The focus of the ETF program has now shifted to reducing its side effects.”BOJ officials told Bloomberg News when contacted for comment that its stock purchases were effective in stabilizing markets, particularly during heightened instability. They added that it was premature to discuss exit strategies from the bank's broad monetary easing measures, including the ETF buying.

Fresh Narrative

At the outset, the BOJ’s plan to buy ETFs was just a sliver of a broader strategy anchored in huge purchases of Japanese government bonds. The stock-fund buying, which had been tested on a small scale in 2010 by Kuroda’s predecessor, was largely seen as a decoration designed to characterize the governor’s asset-buying as more than just a massive bond-purchasing program.

“The BOJ had to show it was taking bold action so it needed to ramp up the ETF purchases too in 2013,” said Sayuri Shirai, a former BOJ board member under Kuroda’s governorship.

Kuroda had dramatically changed Japan’s narrative on fighting inflation, insisting that an intense, concerted effort could achieve its 2% target in around two years. He was backed by newly elected Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who was also on a mission to return Japan’s economy to faster growth.

The success of the experimental ETF program was far from certain. Some economists say that a perfect set of circumstances needed to align: Purchases would have to boost stock prices, prompting companies to cash in by issuing more shares and then investing the proceeds into projects that boost demand and—ultimately—push consumer prices higher.

The initial results were promising. The Topix Index capped a 51% rally in 2013, its third best on record, as foreign investors bought into Abe’s vision, while the Nikkei 225 saw its strongest annual performance since 1972. Prices started rising and—with a temporary boost from a sales tax hike—inflation even topped 3%. In May 2013, The Economist magazine superimposed Abe’s face onto Superman, with the cover line “Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No… It’s Japan!”

As the asset buying continued, though, it became clear that consumer prices weren’t reacting as hoped. And after oil prices plunged in late 2015, inflation headed back toward zero.

Suddenly, the whole effort was in danger of turning into nothing more than a give-away to investors.

In January 2016, with his self-imposed inflation deadline already in the rear-view mirror, Kuroda shocked investors by introducing negative interest rates. It seemed like a last-ditch effort to regain traction on prices. But instead of stimulating the economy, the decision pummeled banking shares, infuriated the public and strengthened the currency as price falls accelerated.

And before the BOJ had a chance to rethink its stimulus program, the U.K.’s shock decision to leave the European Union left the central bank with a huge problem: tumbling equities and a yen that was too strong for the exporter-heavy economy.

Dead Ends

Something had to be done, but what? Simply buying more bonds to calm markets would have gone against the logic of paring back purchases under a new yield-curve control strategy that was still being discussed, people familiar with the matter said. Lowering the negative interest rate was also out of the question, the people added, given the unexpected amount of flak the BOJ had received over the move in the first place.

“The bank was surrounded by dead ends. They were cornered into a place where they couldn’t do anything else,” said Izuru Kato, president at Totan Research Co.

That left Kuroda with only one option: Double the size of the ETF program to 6 trillion yen a year, giving equities an immediate shot in the arm and reassuring markets that the central bank was committed to its goals.

The decision split the bank’s nine-member board, some of whom were already looking for ways to wind down stimulus measures. But Kuroda prevailed and the ETF program soared to a higher altitude on autopilot, stepping in whenever markets fell. Among traders, the rule of thumb at one point became that a decline of 0.5% in the Topix during the morning session would trigger purchases.

Market participants told Bloomberg News that in conversations with the BOJ, they expressed increasing concern about price distortion and thinning liquidity, as the central bank’s ETF ownership approached and then topped 80%. The BOJ listened but didn’t reveal if it shared those worries, the people said.

As the bank’s ETF portfolio expanded, the program gradually morphed into a cure-all for regulators’ gripes about corporate Japan.

In 2016, the BOJ started buying ETFs tracking companies that invest in “physical and human capital”—or those that avoid stockpiling cash hoards and buying back shares. In 2018, it added the MSCI Japan Empowering Women Select Index as a way to promote more female corporate leadership.BOJ officials say that “some points to note have been raised” regarding the impact of its ETF purchases, including their effects on corporate governance.

Very Reliant

Yet as the remit of the BOJ’s ETF buying policy spread ever wider, the bank’s lofty 2% inflation goal remained out of reach.

The reason was simple. ETF purchases had only a “limited power for stimulating aggregate demand,” according to a 2019 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research. When equity prices rose, companies did issue more shares, but they mostly hoarded the proceeds instead of spending them on demand-inducing projects, the researchers concluded.

Then Covid-19 arrived. As the pandemic rattled markets in March 2020, governments and central banks around the globe rolled out unprecedented stimulus measures. The BOJ joined in. It scooped up bonds as the government ramped up spending, and it boosted its ETF buys by 165% in March 2020 from the previous month. It also set an annual cap on buying at 12 trillion yen, double its annual target.

Soon, the central bank overtook the $1.6 trillion Government Pension Investment Fund — the world’s largest pension — as Japan’s biggest shareholder. The new milestone worried policymakers, sources say. In 2021, the Nikkei 225 Stock Average soared above 30,000 for the first time in more than three decades, making the central bank’s support of the stock market even more questionable.

Japan’s ETF market has become “very reliant on the BOJ,” said Rebecca Sin, an ETF analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. She added that it’s also become “very segregated,” given that firms have favored issuing new products to fit BOJ buying guidelines.

At its March 2021 meeting, the central bank concluded that large-scale ETF purchases were effective in stabilizing markets when needed, but omitted mention of their impact on inflation. The implied takeaway was that having that tool on standby made more sense than jumping in whenever markets sneezed.

Last year’s ETF purchases were the lowest since Kuroda took office.

How to Exit

Pausing the buying is one thing. Figuring out what to do with the $430 billion pile of stocks the BOJ has already accumulated is quite another. While bonds will roll off the balance sheet as they mature, ETFs must be actively sold. An exit strategy hasn’t yet been formally discussed, according to people familiar with the BOJ’s thinking. The market value of the ETFs is based off latest figures available from the end of September, not accounting for some small purchases since.There is a precedent for offloading assets. The BOJ has sold commercial bank shares it bought to support private lenders during a domestic banking sector crisis over two decades ago. If the central bank gets rid of its ETFs at the same pace to avoid ruffling markets, JPMorgan analysts estimate it will take 150 years to erase its holdings.

To be sure, the bank isn’t under some kind of mandate to sell down this position; in theory it can hold its position forever. But simply holding on to stock funds that may be worth little in the future also leaves risks for the bank’s finances, the people said. That’s another reason why central banks avoid buying stocks outside of commitments to manage the national reserves, like the Swiss National Bank. The Federal Reserve lacks legal authority to do it.

BOJ officials said that the central bank will record provisions for possible losses if the total market value falls below its cost. However, as the ETF holdings increase further, the impact on the bank's balance sheet would become large, they added.

With Kuroda and his board unwilling to begin a conversation around how to exit stimulus mode, the outlook for the BOJ’s ETF policy is shrouded in what some analysts have described as “strategic ambiguity”—with the central bank neither fully in the market nor fully out, and with no clear guidance on when, if ever, it will depart.

Last month, after the U.S. Federal Reserve announced its first interest-rate hike since 2018, Kuroda vowed to continue Japan’s program of monetary stimulus. While Japan may briefly hit its long-held inflation target in the coming months, “we are not in a position at the moment where inflation is going to reach 2% in a stable manner,” the governor said in parliament.

It is no small irony that the BOJ is an outlier once more—just as it was when the ETF purchases began.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.