Jan 27, 2024

Chevron Says California Plays a Risky Game With Climate and Gasoline

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Chevron Corp. warns its home state of California’s climate policies are a “dangerous game” that risk causing gasoline price spikes and shortages.

The premium California drivers pay for gasoline over the national average is likely to rise significantly if state legislators continue enacting policies to discourage petroleum production, Andy Walz, who leads the oil giant’s US refining division, said in an interview. While the state has the highest penetration of electric vehicles, it’s still the country’s second-largest consumer of gasoline.

California drivers paid an average of $4.94 per gallon of gasoline in the final three months of 2023, about $1.72 above the national average and the highest quarterly premium on record, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The state has the country’s toughest low-carbon fuel standards that are encouraging refineries to convert from petroleum to renewable diesel. Such conversions reduce gasoline supply, pushing up prices, Walz said.

“They knew it was going to happen when they wrote the legislation, he said. “The problem is the consumer is starting to realize it. It’s becoming painful. The way politicians dealt with it was ‘let’s blame the oil companies.’”

Also See: Chevron Would Fit Better in Texas Than California: Javier Blas

California Governor Gavin Newsom’s office said in a statement that the gasoline price spikes the state has experienced have stemmed from oil companies’ own lack of planning.

“Big Oil has been ripping off consumers for decades and lying to protect their profits,” Newsom’s office said.

Chevron’s relationship with its home state has turned increasingly adversarial in recent months. Ever-tightening regulations are squeezing profits and triggered a $4 billion write down of Chevron’s assets, mostly in California. Governor Gavin Newsom has accused Big Oil of price gouging and lying about climate change, both of which are now the subject of investigations and lawsuits. Chevron denies the allegations and says it should not be punished for responding to consumer demand for transportation fuels, which are still heavily weighted toward fossil fuels.

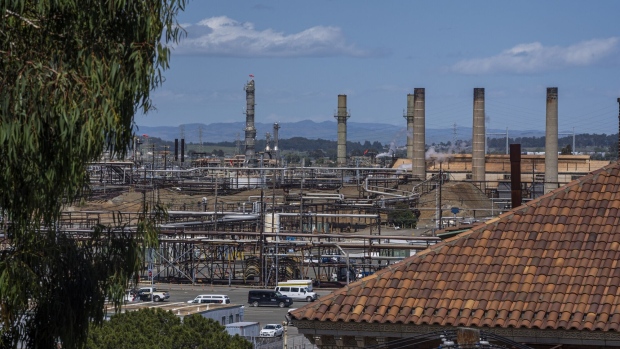

The latest flashpoint is a proposal to establish a maximum refining margin in California. It’s already difficult for Chevron to justify growth projects at its two California refineries — which account for about 30% of the state’s capacity — due to a plan to end sales of internal combustion engines by 2035, which would eviscerate the market for gasoline. But a law that effectively caps refinery profit makes them all-but impossible, Walz said.

“If they cap the upside when conditions are good it’s going to make it really challenging to want to put our money there,” Walz said, adding that Chevron is committed to keeping its refineries safe and reliable. “I cannot compete internally for big capital investments. It doesn’t stack up. I’d rather spend money at our refinery in Mississippi.”

California has long had an outsized influence on national policy, particularly on the environment. The state’s tailpipe emission regulations in the 1970s exceeded those of the federal government but quickly became the national standard because it was easier for automakers meet the country’s toughest regulations set by its biggest market than tailor cars by state. It became known as the “California Effect” and extended to consumer goods and data privacy.

Governor Newsom set a goal for California to become net zero by 2045, five years ahead of US as a whole. Frequent droughts and wildfires mean it is already suffering from catastrophic effects of climate change. The state now gets more than half its power from non-CO2 emitting sources, up from 30% a decade ago and accounts for more than a third of the country’s EV sales. Almost all of America’s renewable diesel, made from vegetable oil and natural fats, is consumed in California.

That success is one reason why gasoline prices are so high. In part to take advantage of state incentives, Phillips 66 is converting its Rodeo refinery northeast of San Francisco to produce 50,000 a day of renewable fuels. Before the conversion, it produced 90,000 barrels a day of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel, representing a 44% overall supply cut.

Chevron and Marathon Petroleum Corp. have made similar conversions, contributing to an 11% reduction in California’s refining capacity over the past decade.

Refiners “are making decisions that are kind of putting us on a pathway where there could be a reliability problem,” Walz said. “You may not have the supply of gasoline if things don’t turn out the way the government wants them to. It’s a dangerous game.”

Conversions also alter the state’s product mix, which is currently awash in renewable diesel but short of gasoline. The problem is magnified because California is essentially an island when it comes to fuel because of a lack of pipelines connecting it with the rest of the country.

“It’s a very risk energy policy situation that we’re headed toward,” Walz said. “If there’s a problem, resupply for California has to come from either Europe or Asia. And that takes a while.”

--With assistance from Chunzi Xu and Mark Chediak.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.