Jun 29, 2022

Desjardins backs Trudeau on inflation, argues against austerity

, Bloomberg News

The major risk period for recession in Canada will be the first half of 2023: Strategist

One of Canada’s biggest credit unions is warning against deeper spending cuts from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government to wrestle down inflation, saying the economy is poised to slow sharply.

Desjardins Securities Inc. entered the debate on how fiscal policy should look amid soaring inflation Wednesday, saying in a report to investors that the government should continue on its current fiscal path.

With the elimination of pandemic aid already acting as a drag on growth, the credit union argued that any further consolidation of fiscal spending would be a “mistake” and hurt vulnerable Canadians who may need support as interest rates rise and inflation bites.

“We’re of the view that the federal government should stay the course,” Randall Bartlett, senior director of Canadian economics at Desjardins, said in the report. “It should follow its current plans to gradually lower spending and let the Bank of Canada do its job on the front lines of the fight against inflation.”

That’s consistent with the relatively dovish outlook for rates at Desjardins. The firm expects the Bank of Canada will raise its policy rate to 2.5 per cent then pause, while markets see it hiking the benchmark to 3.5 per cent over the next year, from 1.5 per cent currently. Desjardins sees the economy growing at 1.1 per cent clip next year, less than half the median 2.4 per cent expected in a Bloomberg survey.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland has come under fire in recent weeks as she fends off criticism that government spending has contributed to inflation, which jumped to a four-decade high of 7.7 per cent in May. With rising prices now the biggest political issue in the country, Trudeau’s team is seeking to downplay its responsibility for ongoing affordability concerns.

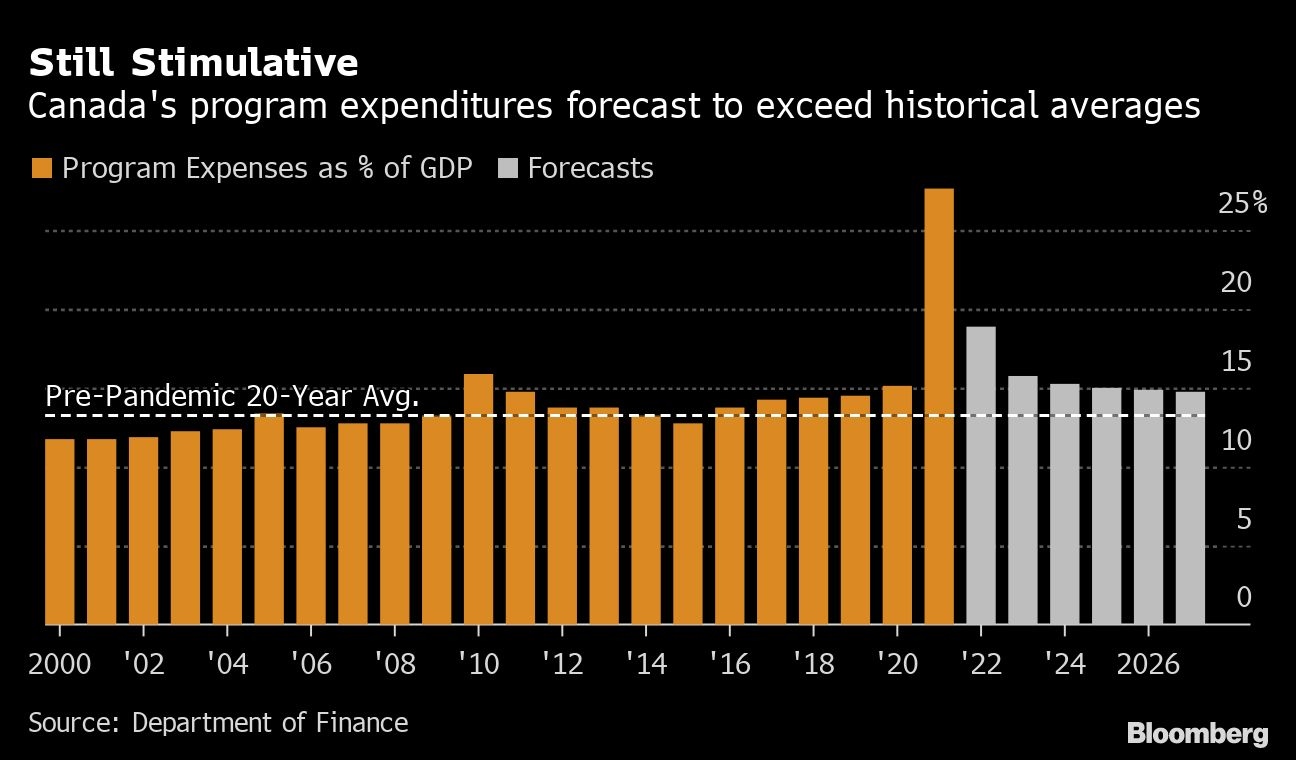

Like other governments around the world, Trudeau’s administration spent big when COVID-19 shut down large parts of the economy: Program spending briefly rose to almost 30 per cent of gross domestic product. In the April budget, Freeland’s department forecast expenses that remain elevated near 16 per cent of GDP over the next year, higher than the historical average before the pandemic.

Much of the direct transfers to households have already been pulled back, Bartlett said, adding that much of the residual transfers have been negotiated to provincial governments or include “measures to mitigate the eroding purchasing power of vulnerable households,” which are “welcome.”

Bartlett also noted that elevated spending in the provinces is forecast to fall more slowly and could represent a better way to reduce fiscal stimulus.

For some analysts, including those at Bank of Nova Scotia, cutting spending would help the Bank of Canada to get inflation back to the 2 per cent target with fewer interest rate hikes, possibly preventing some economic damage in the private sector as output slows.

Critics also say the government is falling short on a promise it made in December to take joint responsibility for fighting inflation along with the Bank of Canada.

The government’s challenge is striking a balance between supporting Canadians and fiscal restraint, Freeland told the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. this weekend, insisting that she doesn’t “want to make the Bank of Canada’s job harder than it already is.”