Sep 9, 2020

LVMH finds a convenient excuse to dump Tiffany

, Bloomberg News

If you liked it, you should have put a ring on it. But Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE, has decided he didn’t like Tiffany & Co. quite enough to consummate his US$16 billion takeover of the iconic U.S. jeweler.

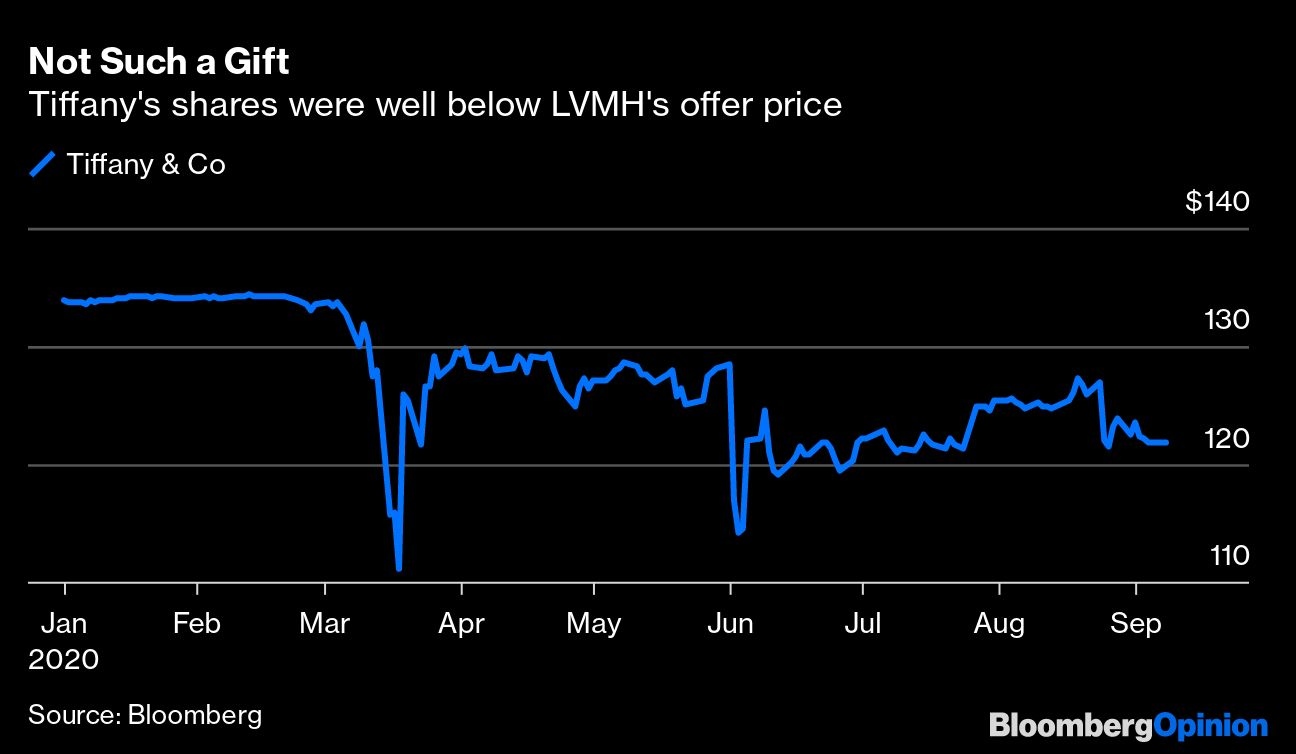

The US$135-per-share deal lost its luster after the luxury world was hit by the global pandemic. Even before LVMH’s decision, Tiffany’s shares were trading at US$121.80. LVMH investors were also already pricing in chances the deal wouldn’t go ahead too. Shares of the French owner of the Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior brands fell just a little more than 1 per cent on Wednesday.

But the timing and reasoning are curious. Two weeks ago, Tiffany announced better-than-expected sales. LVMH is also emerging as a winner from the coronavirus outbreak, as the crisis deepens the division between strong and weak brands. Its market capitalization is still over 200 billion euros, so Tiffany is relatively small.

LVMH blamed the decision on regulatory delays amid a U.S. trade spat with France, and the risk that the U.S. may impose tariffs on French products. It said the French government requested it delay the deal beyond Jan. 6.

That may be a convenient excuse. And once the trade sparring subsides, it leaves the door open to the two reaching a fresh agreement – at a lower price that takes into account market conditions still roiled by a disruption in international travel and economic hardship. After all, the rationale for the deal still stands. LVMH wants to expand in jewelry, and there are few independent luxury groups of scale available. It could easily elevate Tiffany from more affordable luxury to mega-bling status and turbo-charge its sales in Asia.

But if that’s the ultimate goal, it’s a risky strategy. LVMH may not get another chance. Tiffany has already filed a suit against it in an effort to enforce the current merger agreement. A lengthy legal dispute could embitter relations between the two sides.

The bigger danger is that with prized luxury assets, once a opportunity is lost, it rarely comes around again. Other buyers could materialize, especially if Tiffany’s market value continues to decline. Gucci-owner Kering SA or watch-and-jewelry giant Richemont, which counts Cartier in its stable, could yet step into the breach — unless the pandemic makes them nervous about doing a big deal right now, too.

So Arnault may get another chance to buy Tiffany again much later, and at a cheaper price. But the prospects of striking another friendly deal may be hurt by both LVMH’s volte face and subsequent legal wrangling. Already the language between the two looks acrimonious.

After suffering a broken engagement, Tiffany may be wary of saying “I do” to this dashing French suitor again.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.