Nov 2, 2021

Shoppers haven't minded higher prices. That might change soon

, Bloomberg News

Dear shopper, how are you doing? Wall Street is dying to know.

Investors and market strategists are poring over a spate of economic data and commentary from corporate earnings calls, trying to determine how people feel about spending money in these strange times. Some investors are worried and some are jubilant, and there are data to support both perspectives. Yet while it might seem like third-quarter results tipped in the direction of consumer-spending bulls, they should think twice before declaring victory.

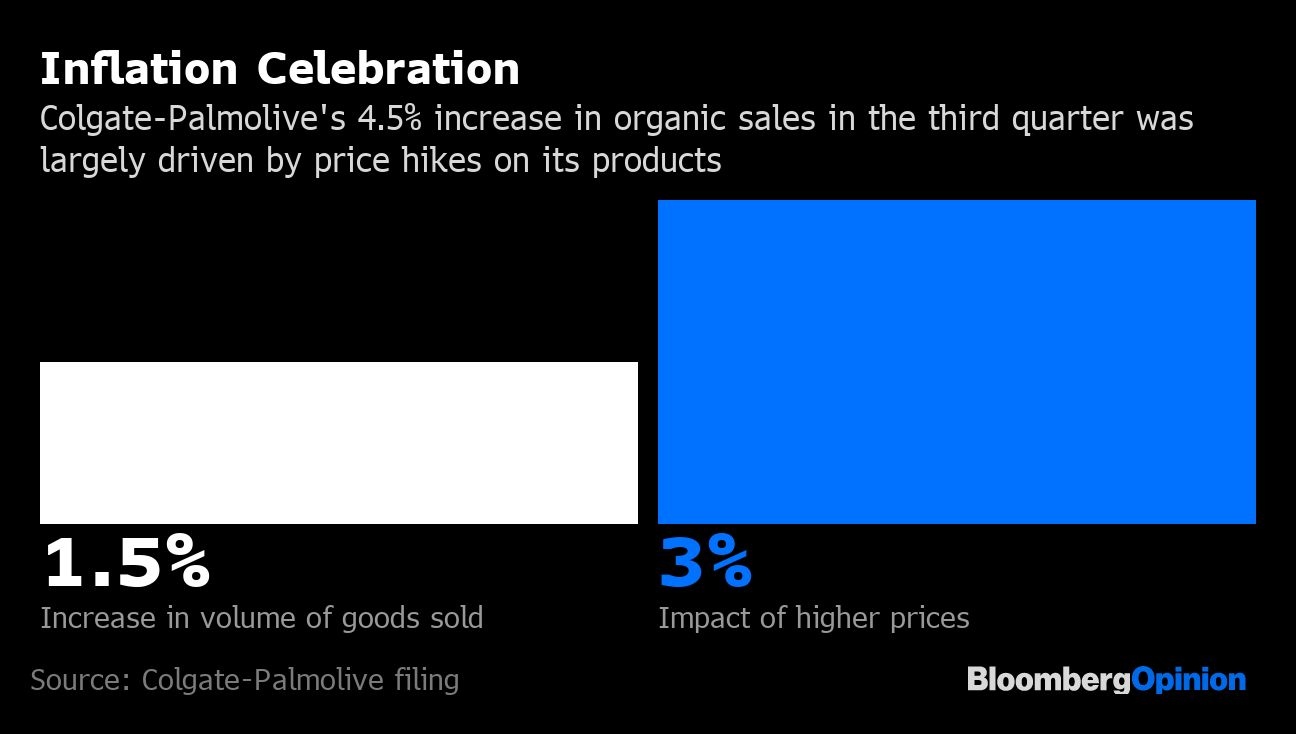

What’s clear is consumers continue to spend more on the basics. Trips to the grocery store, mall and McDonald’s drive-through have gotten more expensive in recent months, and price increases on Hasbro Inc. toys are hitting just as parents start their holiday shopping. Consumer-goods giant Procter & Gamble Co. announced higher prices in nine out of 10 product categories. According to Hershey Co., there is more to come as businesses look to offset the cost of getting goods routed through a clogged freight system and confront workers’ demands for higher pay. Church & Dwight Co., known for its Arm & Hammer brand; Kimberly-Clark Corp., which makes Kleenex tissues; and Starbucks Corp. are among companies leaving open the possibility of further increases heading into the new year.

Overall, business leaders are quite optimistic that consumers will continue to tolerate higher prices. “In the event we feel like we need to pull that pricing lever, we have the ability to do it,” Brian Niccol, chief executive officer of Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc., told earnings call listeners last month. The heads of Keurig Dr. Pepper Inc., L’Oreal SA, Unilever PlC invoked similarly pliable pricing levers.

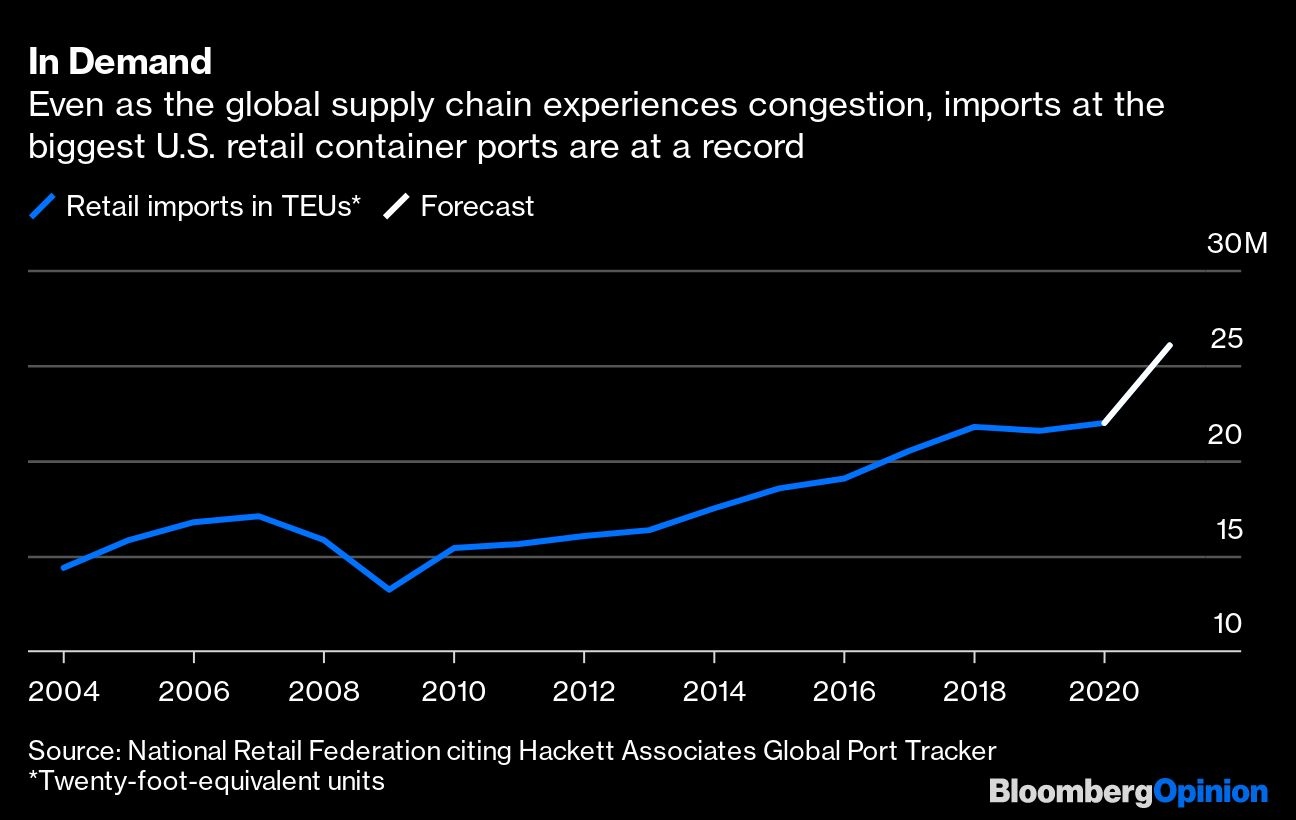

Spending optimists point to the extraordinary buying demand that has persisted throughout the pandemic, fueling the strain on the global supply-chain system. “Congrats on the pricing success so far — it’s better than I expected,” Jason English, an analyst for Goldman Sachs Group Inc., said to Kraft Heinz Co. executives on their call last week. The National Retail Federation expects 26 million twenty-foot-long containers’ worth of retail imports to the U.S. this year, an 18 per cent jump from 2020.

Surveys give the retail federation confidence that with the pandemic rise in wages and saving rates and now vaccinations, holiday spending will be strong. “One way or another they will shop, they will purchase and they won’t go home empty-handed,” Matthew Shay, president and CEO of the NRF, said on a call with reporters Wednesday.

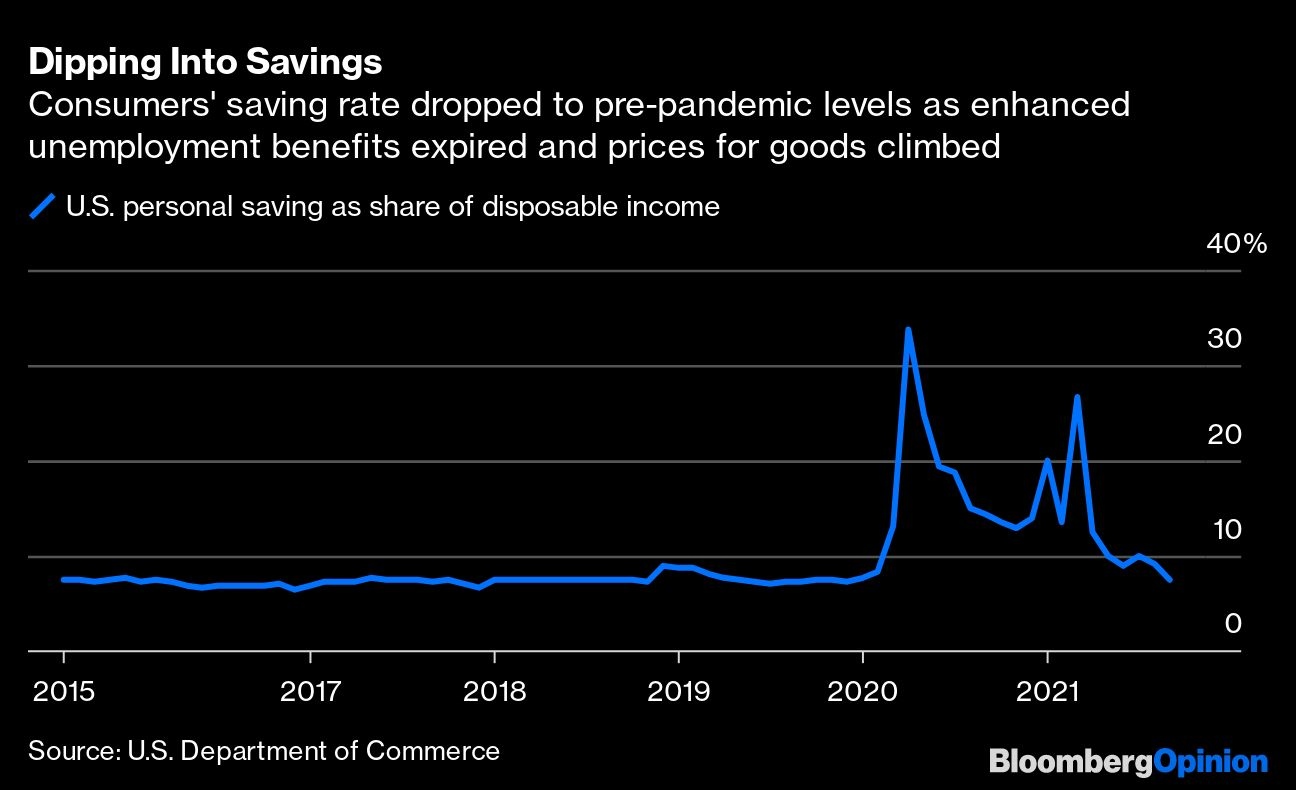

But that read of the situation might prove short-sighted. The latest economic data suggest that, in fact, some consumers might be forced to put the brakes on spending fairly soon. Millions of Americans are still out of work as a near-record number of U.S. job openings remained unfilled in August, and the quits rate hit an all-time high. Meanwhile, wage gains are being neutralized by inflation on everything else. Wage growth will most likely tap out first as people return to the labor force. Their motivation: U.S. personal savings as a share of disposable income fell in September to the lowest rate since December 2019.

Companies risk being too cavalier about raising prices and too focused on avoiding a few quarters of earnings pressure. What shareholders would hate more than profit margins temporarily contracting is to see sales growth fall off a cliff because businesses were so focused on supply chain troubles that they misread consumer sentiment.

One explanation that has been used for the labor and supply shortages is the relief money provided by the federal government. The reality is far more complex. Domino’s Pizza Inc. pointed to workers’ difficulty obtaining child care and lower levels of immigration for its struggle in finding delivery drivers. Drug addiction and a mismatch between skills and need are other drags. The NRF blamed the troubled state of U.S. infrastructure, such as poorly maintained roads and ports in need of dredging: “The pandemic didn’t so much as create these problems in our supply chain as illuminate the kind of under-investment that has occurred in this country over many decades,” Shay said.

For now, consumers seem unfazed by higher price tags, and that is helping companies eke out strong earnings. But what happens if this obsessive focus on pricing and supply-chain diversion tactics — such as retailers securing their own shipping vessels — are distracting from a set of deeper problems around labor and infrastructure? We’ll soon find out.