Nov 13, 2018

Waymo to Start First Driverless Car Service Next Month

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In just a few weeks, humanity may take its first paid ride into the age of driverless cars.

Waymo, the secretive subsidiary of Google’s parent company, Alphabet Inc., is planning to launch the world’s first commercial driverless car service in early December, according to a person familiar with the plans. It will operate under an entirely new brand and compete directly with Uber and Lyft.

Waymo is keeping the new name a closely guarded secret until the formal announcement, said the person, who asked not to be identified because the plans haven’t been made public.

“Waymo has been working on self-driving technology for nearly a decade, with safety at the core of everything we do,” the company said in an emailed statement. A Waymo spokesperson declined to comment on the name of the new service or timing of the launch. It’s a big milestone for self-driving cars, but it won’t exactly be a “flip-the-switch” moment. Waymo isn’t planning a splashy media event, and the service won’t be appearing in an app store anytime soon, according to the person familiar with the program. Instead, things will start small—perhaps dozens or hundreds of riders in the suburbs around Phoenix, covering about 100 square miles.The first wave of customers will likely draw from Waymo’s Early Rider Program—a test group of 400 volunteer families who have been riding Waymos for more than a year. The customers who move to the new service will be released from their non-disclosure agreements, which means they’ll be free to talk about it, snap selfies, and take friends or even members of the media along for rides. New customers in the Phoenix area will be gradually phased in as Waymo adds more vehicles to its fleet to ensure a balance of supply and demand.

The launch of a commercial ride-hailing service will mark an end to the intense secrecy that’s surrounded Waymo’s program—and self-driving research in general—since Google first started working on it a decade ago. “This positions Waymo really far ahead of everyone else,” said Nick Albanese, an intelligent mobility analyst at Bloomberg New Energy Finance. “GM is the other leader, and they’re probably more than a year away from doing this. It’s very impressive.”

Being first has its advantages. It establishes credibility and allows Waymo to build out a network of vehicles, maintenance depots and support services robust enough to draw customers away from Uber and Lyft. The early start also makes Waymo’s ride-hailing service worth about $80 billion—even before the service is launched—according to an analysis by six Morgan Stanley analysts in August.

Opportunities in trucking logistics and technology licensing add another $96 billion in current value, according to the analysts. Those lines of business will still fall under the Waymo umbrella. The new brand launched in December will only apply to the ride-hailing app and is meant to differentiate it from the other services, according to a person familiar with the company’s strategy. Still, Waymo doesn’t have an insurmountable head start. GM plans to start a similar ride-hailing service late next year, while Tesla, Daimler, Volkswagen and other competitors aren’t far behind—each with their own approach to solving the technological and social challenges of taking human drivers out of the car.

What to Expect in December

When Waymo starts its commercial program, there will be backup drivers in the car to help ease customers into the service and to take over if necessary, according to the person familiar with the plans. The fleet of heavily modified Chrysler Pacifica minivans will drive themselves more than 99.9 percent of the time, based on data from Waymo’s test program submitted to California regulators.

Some volunteers in the Phoenix Early Rider Program won’t switch over to the new commercial program, the person said. Instead, they’ll continue to be used to test new features and offer feedback to the company. For example, volunteers occasionally receive cars with no backup driver in the car at all. That will continue with increasing frequency until the commercial service is ready to take that step.

Waymo’s plan is to plant the seeds of these drivereless car programs in different metro areas across the U.S., and to gradually expand outward. It’s a careful, almost plodding process meant to avoid the bad customer experiences and avoidable crashes that could set a program back by years. By the time Waymo’s service becomes a household name in the U.S., like industry giants Lyft or Uber, the company will have mapped and tested every road in excruciating detail. Waymo’s turtle approach is in marked contrast to Tesla Inc.’s hare strategy. Elon Musk’s trailblazing electric carmaker is working on a self-driving approach that would activate almost simultaneously across a nationwide fleet of hundreds of thousands of cars.

Waymo’s Phoenix program may seem tiny compared with that plan, but last week Waymo won approval to begin testing cars with no backup drivers in California’s Silicon Valley, where Tesla’s Autopilot team is based. Waymo already has dozens of driverless vans operating out of Alphabet’s X lab in Mountain View to provide a daytime taxi service for employees. The next step will be to start an Early Rider Program based on the Phoenix model and eventually launch a commercial program in Musk’s backyard.

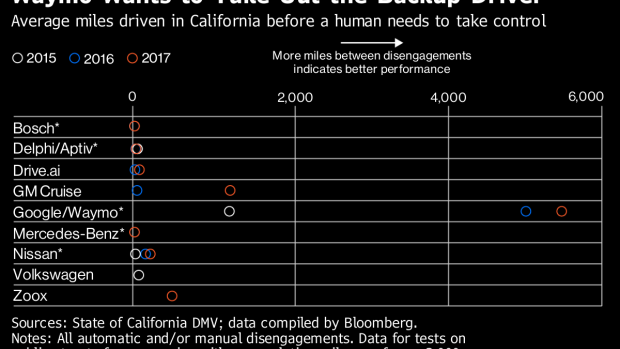

There are other ways to quantify Waymo’s early advantage against its rivals. California requires detailed reporting from every company testing cars there, and the results show Waymo far ahead of competitors testing on public roads in the state. The chart below shows the number of miles driven, on average, before a human took control of the car.

How Much Will It Cost?

Waymo is just beginning to experiment with pricing models. For now, the program is more about learning how to safely scale driverless cars than making money. At launch, Waymo will use a crude calculation of distance and time that will result in fares that are competitive with Uber and Lyft, according to the person familiar. A view of the Waymo app in July by Bloomberg showed a streamlined user-interface that resembled Google’s navigation app, with the additional functions of a standard ride-hailing app.

Eventually, the pricing scheme will become more nuanced: possibly adding fees for making a vehicle wait too long, cleaning costs, tolls and surge pricing when demand outpaces supply. Once the backup safety drivers are taken out of the equation and Waymo figures out how to charge for in-ride entertainment and advertising, base fares are expected to drop. There’s currently no plan for a subscription model where drivers would pay a set fee to have unlimited access, according to the person.

Are Driverless Cars Really Happening?

In a Bloomberg tour of Waymo’s Phoenix program in July, dozens of minivans shuttled in and out of a nondescript depot in Chandler, Arizona. Waymo had just doubled the depot size to almost 70,000 square feet. A handful of dispatchers managed a fleet of hundreds of vehicles, and new vans were arriving each week.

One could argue that Waymo’s commercial program is just another incremental step in its decade-old development program. After all, there will still be backup drivers, customers will have to wait to join, it will only operate in a tiny geographic area with ideal driving conditions, and it’s still years away from being a profitable, stand-alone business.

But Waymo (or whatever it’s going to call itself) has reached deals to acquire as many as 62,000 plug-in hybrid Pacifica minivans and 20,000 fully-electric I-Pace SUVs to build out its fleet over the next few years. There are test cars on the road already ferrying passengers with no backup drivers, and starting next month, Waymo’s newly branded service will start selling rides to its first true customers. The age-old guessing game of how long it will take for cars to drive themselves has come to an end. The better question now: How long will it take them to reach me?

To contact the author of this story: Tom Randall in New York at trandall6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at drovella@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.