Oct 29, 2022

Why Do We Give Out These Confounding Book Awards Each Year?

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- What good are book prizes? No disrespect to Shehan Karunatilaka, who has just picked up £50,000 ($58,000) for winning the Booker Prize with his novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, but awards take the painstakingly crafted stories of disparate authors and put them through a demolition derby of readings and judging rounds. Winners often emerge after an unedifying process of horse trading.

There’s no suggestion that this occurred in Karunatilaka’s case, but poet Philip Larkin threatened to jump out of a window in 1977 unless his fellow judges awarded the Booker to Paul Scott’s Staying On. (They did.) Prizes require those essentially diffident and solitary types—writers—to parade themselves like show ponies. Critics say that awards encourage a particular type of book, modish or politically correct, that may have limited appeal. Real Life by the American author Brandon Taylor has many sterling qualities, but it would take a bold , broad-minded reader to pick it up on the recommendation of the judges responsible for the 2020 Booker shortlist: “[A] deeply painful, nuanced account of microaggressions, abuse, racism, homophobia, trauma, grief and alienation.”

Seven Moons concerns the bloodshed that has roiled Karunatilaka’s native Sri Lanka for many years. A postgraduate researcher at the University of Liverpool, Naomi Adams, correctly tipped it to win the Booker after a close reading. Adams wrote: “Historical fiction? Check. Past-tense deep dive into recent postcolonial trauma? Check.” (I hope she backed her hunch with a bookmaker.) Writers who make solid, readable books that readers actually like rarely get much of a chance. The thinking behind awards is that they encourage us to notice important new books, as we did in the old days—some of us, at least—before there was so much competition for our poor, reddened eyeballs. In this noble undertaking, prize-giving committees often succeed. But what do awards mean for writers, and for the written word in our culture?

Last week, Karunatilaka accepted his trophy from Camilla, Britain’s queen consort, at a rock ‘n’ roll venue, the Roundhouse in London, following a speech by Dua Lipa. The Booker is awarded for “the best sustained work of fiction” written in English and published in the UK and Ireland. A few years ago, I talked with all the writers who were on the Booker shortlist that autumn. We met in an old factory in London that’s familiar to millions of viewers as the home of Dragon’s Den, the reality show for wannabe entrepreneurs. Seldom had this cockpit of desire witnessed a life-changing opportunity like the one I was discussing with the inky hopefuls. What struck me was how handy the prize money would be for them. One well-known British novelist in the running told me that she could only afford to write for a living because she had bought a house outside London and had no children. Another contender said he had once taken on the job of ghost-writing a rich man’s memoirs. “I was laboring at the time, broke, and my wife was pregnant with twins, and we were in pretty desperate straits,” he said.

Badly heeled writers of literary fiction can hope to see their fortunes turned around by the so-called “Booker Bounce” that follows a win.

According to publishing folklore, the Booker laureate can leave a routine of unheralded struggle in coffee shop corners and embrace a life of fame. Does it really turn out that way? Some winners never appear in bestseller rankings again. DBC Pierre, who won the Booker in 2003 with his debut novel Vernon God Little, has described his difficulty in fulfilling the potential that the award seemed to proffer. He thought the win would “buy me space,” but it brought him the opposite, he said.

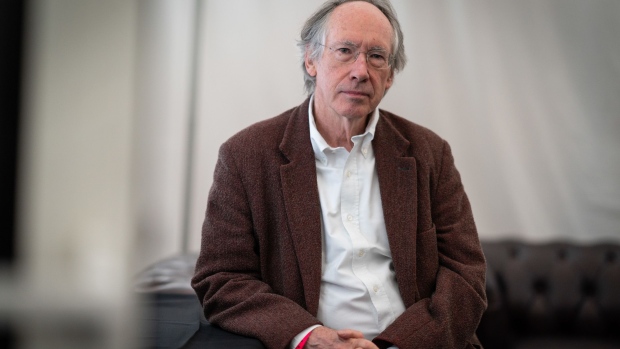

Some writers have good reason to thank the Booker judges. Since Ian McEwan carried off the prize in 1988, he has gone on to accumulate a wide readership as well as literary gravitas. He told the awards ceremony that he could afford to spend money on “something perfectly useless” instead of putting it aside for “bus fares and linoleum.” Anna Burns won the Booker in 2018 after subsisting on what she could find in food banks. She said she would use the proceeds to “clear my debts and live on what’s left.”

Before Damon Galgut won in 2021, he had sold just over 9,000 copies of The Promise, about the downfall of a white family in South Africa after the end of apartheid. The Promise rang up sales of 14,622 in the next two weeks alone, and Galgut’s publishers ended up printing an additional 153,000 copies. Perhaps the greatest feel-good story around the Booker in recent years concerned Bernadine Evaristo, who shared it with the veteran Margaret Atwood in 2019. Evaristo, who was born in London in 1959, was well regarded as a poet and novelist but wasn’t selling many books before winning the prize. Her novel Girl, Woman, Other was soon on the Sunday Times bestseller list alongside blockbusters by Stephen King and James Patterson. Within days of her win, her sales more than doubled: She had sold 4,391 hardbacks in the previous five months, but her sales jumped to 10,371 within a week. She went on to publish a memoir of the writing life, Manifesto: On Never Giving Up.

As for Karunatilaka, he is still adjusting to the kind of attention that can upend a settled existence. At 47, he makes his living as a copywriter and has no immediate plans to quit the day job, he told reporters. He said the “bread and butter stuff” takes the pressure off him to support his wife and two children solely through writing. “If you’re full-time writing and the draft is crap, you’ve wasted your time. A crap draft is not going to feed my family.”

Still, if my local bookstore in West London is any kind of weathervane, things look well for Karunatilaka: The shop has ordered 80 copies of Seven Moons. Before the Booker shortlist was announced, you’d have been lucky to find more than two copies of this title on the shelves there. This is a tremendous fillip for his small publisher, Sort of Books, which launched in 1999 with a staff of two.

The Booker is the most eye-catching and prestigious of the UK’s book awards, which include the British Book Awards (aka “the Nibbies”); the Baillie Gifford Prize for nonfiction; and the Costa awards, which recognize titles in five different categories: first novel, novel, biography, poetry and children’s book. In 1998, when the Booker was worth £10,000, the poet and critic Ian Hamilton calculated in the London Review of Books that a canny, adaptable author could pocket £20,000 in prize money a year (about £34,500 today and well above the national average wage). Almost 2 ½ decades later, the median annual income of a professional writer has slumped to £10,500, according to the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society. That’s well below the minimum wage—and amounts to a 42% drop in real terms since 2005.

Evaristo says in Manifesto: “I have found that developing self-belief is more important than relying on the approval of others, because when times are hard and you feel alone, you need to marshal your inner resources to keep going.” Most writers are creating for love, or for another compulsion, though a little money doesn’t hurt. The prospect of winning a prize, however distant and chimerical, can help a novelist persevere and ignore the voice in their head that mutters, over and over the crushing exit line of the Dragon’s Den judge: “I’m out!”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.