Apr 18, 2024

Creditor Betrayals Pit Invesco Against Bain in Bankruptcy Rumble

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Matthew Brooks stared at the numbers glowing on his screen in disbelief. Somehow, a big slug of cash — some $92 million — was about to hit Invesco’s accounts.

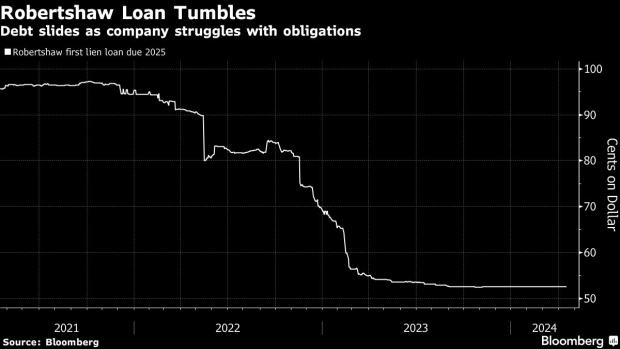

It’s the kind of news that investors typically delight in receiving and yet Brooks, a managing director in Invesco’s distressed credit group, was alarmed. And puzzled. The payment had come from Robertshaw, a maker of washing machine parts based in Itasca, Illinois. That made no sense to him. The company had been so cash-strapped just days earlier that it was on the cusp of bankruptcy and now somehow it’s cutting big checks to pay back its loans? How?

This, Brooks immediately knew, was a huge problem for Invesco, which had been preparing internally to fund Robertshaw’s restructuring — a process that would likely see it own the business out of bankruptcy. The debt they intended to leverage in Chapter 11 was suddenly erased from the company’s balance sheet and, along with it, something far more valuable than the cash flooding into the firm — control.

Up until then, Invesco owned a majority of Robertshaw’s most senior debt, granting them the coveted position of “required lender” and giving them the right to influence the company’s reorganization. The surprise December repayment meant someone had snatched that away.

“We have potentially lost req lender here,” Brooks messaged an associate that night. “And idk [how] we control this.”

It turned out that Bain Capital Credit, Eaton Vance Management and Canyon Capital Advisors — three lenders Invesco worked with months earlier on a controversial financing for Robertshaw that pushed other creditors down the repayment line — were tipped off to Invesco’s plan, and responded by concocting their own deal with Robertshaw and owner One Rock Capital Partners, which welcomed a chance to avoid bankruptcy.

It would spawn dueling allegations of lender-on-lender betrayal that burst into the open when Invesco sued to block the competing transaction. Even by the standards of the past few years — a period in which conflicts between creditors have exploded — the speed with which one-time collaborators became courtroom foes in the Robertshaw feud is surprising, and shows how far sophisticated, deep-pocketed firms are willing to go to control corporate restructurings.

“Some of the funds that do these kinds of transactions can be fairly described as on the aggressive side of the market,” said Thomas Kessler, a restructuring lawyer at Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton. “What comes along with that is, they’re going to be pretty pissed when they lose.”

This account is based on conversations with people familiar with the Robertshaw transactions as well as bankruptcy records, email correspondence, presentations and deposition testimony made public earlier this month by a New York state judge overseeing the lawsuit.

Spokespeople for Invesco, Robertshaw, Bain and Eaton Vance declined to comment. One Rock didn’t respond to requests seeking comment, nor did lawyers representing Canyon in the bankruptcy.

Just before Thanksgiving, Brooks had dinner with Robertshaw Chief Executive Officer John Hewitt to discuss turnaround plans for an unglamorous business that makes water valves for washing machines, top burners for gas stoves and cold thermostats and electronic control panels for refrigerators.

Weeks earlier Invesco, which had amassed about $72 million of Robertshaw’s most senior debt along with around $242 million in lower-ranking obligations, had used its position to propose an agreement that was kept secret from other lenders. It required Robertshaw to ready an Invesco-led bankruptcy that could be initiated as soon as January, according to the company.

Hewitt expressed concern bankruptcy would complicate his company’s relationship with a key customer. But Brooks, a distressed debt veteran, had worked with skittish CEOs and CFOs before, and said in a deposition that he believed their concerns about bankruptcy were “often very overblown.”

He thought Chapter 11 could be a huge help to Robertshaw by cutting a substantial amount of debt, much of which could be traced to the 2014 leveraged buyout of the company by its previous owner, Sun Capital Partners.

It didn’t hurt that Invesco would likely take control of the business in a Chapter 11. Internally, Invesco projected returns nearly double its investment if it took over the company via bankruptcy.

Robertshaw agreed under the Invesco deal not to take on more debt. That’s why the notice Brooks got in December didn’t make sense: somehow, Robertshaw had repaid Invesco’s senior loan, along with a roughly $20 million premium.

What Brooks didn’t know was that around the same time he was having dinner with Hewitt, Bain, Eaton Vance and Canyon had caught wind that Invesco was preparing Robertshaw for bankruptcy.

The four firms had teamed up about seven months earlier to provide the company with fresh financing, and Invesco’s decision to cut the other three out now was, for them, nothing less than a betrayal.

The trio acted quickly. Over the course of a few weeks, they provided Robertshaw with more than $40 million and repaid nearly all of Invesco’s senior debt by requiring the company borrow an additional $228 million.

Invesco’s head of distressed credit, Paul Triggiani, immediately thought the payment was prohibited by their agreements with the company, but pressed a colleague to start buying junior debt to protect the firm’s position. The request was so urgent Triggiani said to buy the debt “even at par” if necessary.

For more distressed debt coverage, subscribe to The Brink

“How is this possible?” was the first thing that went through Brooks’ head, according to his deposition. “We had strictly prohibited the incurrence of additional debt to repay debt.”

It would soon become clear. According to Robertshaw’s lawyers, the manufacturer’s corporate parent created a new company called RS Funding. Robertshaw used borrowings from the new entity to repay Invesco, allowing Bain and the others to assume the mantle of required lender. The prohibition on incurring more debt applied to subsidiaries of Robertshaw, a restriction that didn’t apply to RS Funding because it exists underneath Robertshaw’s ultimate parent, according to the company.

Invesco sued in New York state court on Dec. 20, calling the Bain deal an “illegal sham transaction.”

Lawyers for Robertshaw, One Rock, Bain, Eaton Vance and Canyon have defended the maneuver, saying it was authorized under the relevant credit agreements and averted a rushed bankruptcy. “Invesco, as a sophisticated investor, knew that its first-out term loans could be voluntarily prepaid at any time,” they said in court.

An attorney for other Robertshaw lenders, who were already suing to block the refinancing transaction from seven months earlier, said in court that Invesco, Bain, Eaton Vance and Canyon had turned on creditors, and then turned on each other.

‘Unfortunate Mess’

Bain’s December financing was supposed to give Robertshaw more time to implement its turnaround, but the company and its backers said the runway was eaten up after Invesco sued to retain its required lender status. Robertshaw was required under an indemnity agreement to cover the lenders’ legal costs, which soaked up cash intended to turn around the business, attorneys have said.

It became too much for Robertshaw to handle. The company filed for Chapter 11 in February, a decision that put the Invesco lawsuit on hold.

Robertshaw’s path out of bankruptcy remains uncertain. Invesco and Bain, Eaton Vance and Canyon have each offered to fund its reorganization, a sign that financiers still see potential in a turnaround. The dispute could be resolved through mediation, and Robertshaw settled the earlier lawsuit brought by other lenders over the May debt deal last month.

Invesco lawyer Andrew Glenn said at a recent hearing that it’s possible mediation can unwind the dispute, but shared a grim assessment that’s been echoed by other lawyers.

“This case is an unfortunate mess,” he said.

--With assistance from Reshmi Basu.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.