Dec 16, 2023

Scholz’s Budget Respite Leaves German Destiny Shrouded in Doubt

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- German Chancellor Olaf Scholz may have clinched an accord on a budget for 2024, but his coalition has a lot more questions to answer about the country’s destiny.

The hard-fought fiscal agreement in Berlin on Wednesday fixes only one immediate challenge overshadowing Europe’s biggest economy, whose healthy public-finance profile has come at the cost of an investment drought compared with rich-world peers.

Tens of billions of euros of spending on the energy transition and infrastructure are now threatened after a court ruling that cast doubt on governments’ off-budget method of financing. Without such commitments, Germany’s drive to shore up competitiveness and generate meaningful growth could be impaired for years.

A reform of the constitutional debt brake, the fiscal limit at the heart of the dispute, will likely feature a battle for the country’s soul that may ultimately need to be determined by voters. For now, Scholz, his deputy Robert Habeck and Finance Minister Christian Lindner are embracing leaner government by cutting spending by €30 billion ($32.9 billion) next year.

“Given the precarious state of at least parts of our industry and significant gaps in public investment, this turn to austerity could inflict serious damage,” said Philippa Sigl-Gloeckner, a former finance ministry official who leads Dezernat Zukunft, a Berlin-based research group. “One can only hope the German debate can advance to the real world before it’s too late.”

Sigl-Gloeckner’s complaint is that the country’s adherence to financial prudence, enshrined in 2009 with the debt brake and often manifested through so-called “black zero” balanced budgets, has let the economy rot.

Germany is the only Group of Seven member with borrowings far below 100% of output and a string of top credit assessments, underpinned by what Scope Ratings describes as a “strong track record of fiscal discipline.”

But the company also reckons that underinvestment over the past decade totaled €300 billion compared to similar-rated economies.

Evidence of the trade-off isn’t hard to find. Last month, only one in two long-distance trains reached their destination on time. The country’s mobile-phone networks are often patchy, and progress in digitization has been notably slow.

Germany slipped seven spots this year to 22nd in the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook, and ranked even lower in categories covering government and business efficiency. Students fared worse than ever in a major international test, underscoring education shortfalls too.

While bureaucracy and inefficiency don’t help, lack of money is a key constraint. A recent study put a €372 billion price tag on maintaining and extending the communal road and rail network.

The government’s priority on the climate transition requires even more resources. State-owned development bank KfW estimates that achieving carbon neutrality by 2045 requires public investment of just under €500 billion — or about €20 billion a year.

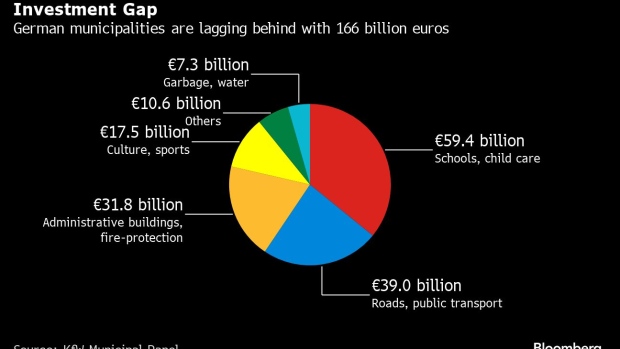

More than half of municipalities, responsible for a big portion of the country’s investment backlog, say they’re financially ill-equipped to spend more.

Meanwhile the fruits of doing more could be huge. Bloomberg Economics’s Martin Ademmer estimates that a catchup toward the average spending ratio of G-7 peers alone could raise total output by nearly 2% by 2050.

“Targeted higher public investment provides a boost to gross domestic product in the long run,” he said. “It’s much needed, because a shriveling labor force will cause growth to decline in the coming decade, and the challenges of economic transformation toward climate neutrality represent a notable downside risk.”

The government’s method to address that was to funnel spending via special funds that weren’t part of the federal budget. That was until the ruling by Germany’s constitutional court last month.

Scholz and his colleagues found themselves in a crisis as they raced to recalibrate fiscal plans both for this year and next. And unlike 2023, when the energy squeeze became the pretext to suspend the debt brake, that won’t happen in 2024 — meaning cutbacks.

The chancellor insists that spending “significantly less money” won’t alter his government’s determination to support the climate transition and strengthen social cohesion. But Siegfried Russwurm, president of industry lobby group BDI warned of a “severe impact” that will hamper the economy’s recovery.

For Jasmin Groeschl, a senior economist at Allianz, fiscal policy could now become a “major brake on growth.”

She forecasts expansion of only 0.5% next year — just over half the 0.9% pace that the International Monetary Fund predicted before the court ruling — but also sees the risk of a contraction if the government underestimates spending needs.

The bigger question for the future is how and whether Germany’s political class can redesign the debt brake that limits net new borrowing to just 0.35% of GDP annually. While strict, it’s arguably less stringent than the balanced-budget rule in neighboring Switzerland.

Any change would require a two-thirds majority in parliament — impossible without support from opposition lawmakers such as the conservative Christian Democrats, who lead in the polls and are trying to profit from the coalition’s predicament.

Even inside the government, there’s no agreement on how to proceed. Scholz’s Social Democrats and Habeck’s Green’s are in favor of loosening the rule, while Lindner of the Free Democrats has invested huge political capital in preserving it.

One argument to keep the brake is that it stores up fiscal firepower to use in times of crisis, as Europe has often benefited from in recent years.

Lindner’s closest advisor, Lars Feld, also says that companies should be doing the investing, and the government shouldn’t supplant that and add to its borrowings in the process. He favors regulatory reform instead.

“Better legislation can reduce bureaucratic costs, which are currently the main obstacle to investment activity,” he told Bloomberg. “Corporate taxes should also be reduced.”

Sigl-Gloeckner counters that the government’s latest fiscal agreement shows that it’s on a damaging austerity drive that goes even further than it needed to.

The budget cutback “was neither required by law nor does it make economic sense,” she said. “This looks to me like the return to the dark ages — of ‘black zero’ ideology.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.