Apr 17, 2024

What Went Wrong With US Inflation

, Bloomberg News

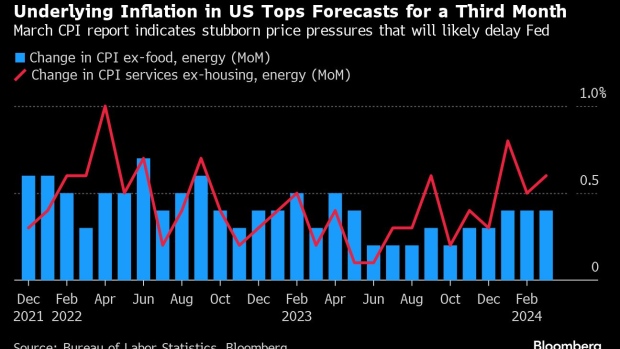

(Bloomberg) -- This was supposed to be the year that US inflation rode the last mile down to 2%, letting the Federal Reserve steadily reduce interest rates from a two-decade high. Now those expectations have been dashed.

Price gains have proven much stickier than anticipated a few months into 2024 amid a resilient economy and labor market. On Tuesday, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said persistent inflation means borrowing costs will stay elevated for longer than previously thought, a shift in tone with ramifications for policy around the world.

A persistent shortage of housing is partly to blame, as are rising commodity prices and car insurance premiums. But some also point to Powell himself for prematurely telegraphing interest-rate cuts, which ignited optimism in financial markets and fueled economic activity.

“They just got the inflation picture wrong,” said Stephen Stanley, chief US economist at Santander US Capital Markets LLC. “The mistake they made was they got really enamored with the combination of really strong growth and benign inflation that we saw in the second half of last year.”

Traders now see just one to two rate cuts this year from the current level of 5.25% to 5.5%. That’s a far cry from the roughly six they expected at the start of 2024, and the three that Fed officials penciled in just a month ago. Investors and economists are flagging the chance of no cuts at all this year.

Fed officials maintain that inflation is still broadly on a downward trend, but they’ve also stressed that borrowing costs won’t be moving lower until they’re more confident in that trajectory.

While much of the inflation damage has been most evident in the consumer price index — which accelerated to 3.5% in March from a year earlier — the Fed’s preferred metric is the personal consumption expenditures price index. The PCE has been running closer to the central bank’s 2% target — registering 2.5% in February — but progress on that gauge has also stalled.

Here are some reasons for the latest wave of US inflation:

Shelter, Insurance

Shelter, which accounts for about a third of the CPI, has proved the most stubborn. Despite some timelier measures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Zillow Group Inc. and Apartment List that show rent growth for new leases coming down, the corresponding components in the CPI have yet to reflect that.

Part of the delay is because most tenants don’t move in a given year. That’s especially true now for homeowners as well, many of whom locked in cheap mortgage rates during the pandemic and don’t want to take on a new one above 7%.

Also, the construction of the index plays a role: Units are sampled only every six months, which means changes in rents take time to work through the monthly data.

The PCE, meanwhile, assigns shelter a much lower weight, which helps explain why it’s trended lower than the CPI.

Another driver of inflation is insurance costs. Tenants’ and household insurance is rising at the fastest rate in nine years, while auto insurance skyrocketed 22.2% in the year through March, the most since 1976. A key reason: Cars are more technologically complicated now and therefore cost more to repair.

Commodities

After falling for much of last year, energy prices — specifically oil — climbed in the first quarter, and an escalation in the war in the Middle East threatens to push them even higher. The rally has translated to more expensive gasoline. Electricity prices have also climbed.

Central bankers prefer to look at so-called core measures of inflation, which strip out food and energy prices that can be volatile. They’ve also eyed an even narrower gauge known as “supercore,” referring to services costs excluding energy and housing — and even that’s been too strong due to a robust labor market.

But the surge in the price of oil and other raw materials is impossible to ignore, as it can filter through to costlier shipping and merchandise. Gasoline and shelter combined accounted for over half of the monthly advance in the March CPI.

Powell Pivot

In December, Powell spurred big market bets on rate cuts by saying such moves were “clearly” a topic of discussion.

The comments’ effect was equal to lowering interest rates by 0.14 percentage point — and also will add about a half percentage point to the CPI this year, according to Anna Wong, chief US economist at Bloomberg Economics.

Now Powell “is entertaining the possibility that disinflation has indeed stalled, and that the bar for cutting rates may have increased,” Wong said. “That raises the risk that there won’t be a rate cut this year, if the unemployment rate is little changed from today.”

Market Euphoria

In addition to the economic impact since Powell’s December remarks, stocks and bonds have added $7.5 trillion to their combined values through the market’s peak in March — equivalent to roughly 30% of US gross domestic product.

The prospect of lower rates has encouraged investors to bid up risky assets of all stripes. The S&P 500 has scored 22 record highs in 2024, while corporate bond risk premiums — the extra yield investors demand over Treasuries — narrowed this month to a more than two-year low.

All of this is contributing to a material easing in financial conditions, with a Bloomberg index tracking the investment backdrop now more accommodative than before the Fed embarked on its aggressive tightening two years ago.

Claudia Sahm, a former senior Fed economist, blames markets, not Powell. “The degree of motivated listening is mind blowing,” said Sahm, chief economist at New Century Advisors LLC.

--With assistance from Matthew Boesler, Lu Wang and Sid Verma.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.