Feb 15, 2024

How Third Party Candidates May Cause Trouble for Biden or Trump

, Bloomberg News

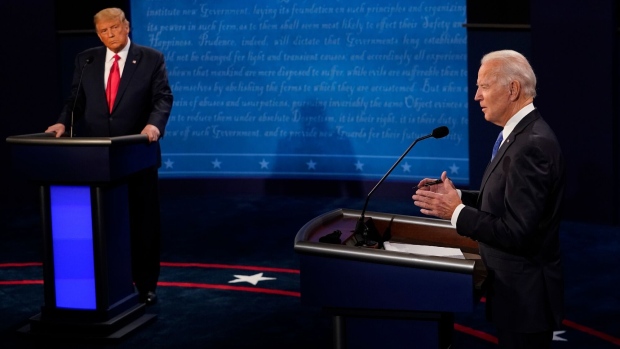

(Bloomberg) -- American voters are so disillusioned by their options in the presidential election that pollsters have come up with a term for it: “Double-hater.” These are people who don’t like President Joe Biden or former President Donald Trump, who leads the race for the GOP nomination. And yet, when asked by the Big Take DC podcast if an outsider candidate could break through in 2024, Ralph Nader, who ran for president outside the two major parties four times, gave a simple, “No.” Still, there are some indications that third-party candidates could cause trouble for the frontrunners.

Nader says there are too many roadblocks for a third-party candidate to contend with. “It’s the hardest democracy, so called, in the Western world, just to get on the ballot,” he says. “It was like climbing a sheer cliff with a slippery rope.”

And that cliff is high. White House reporter Gregory Korte explains that third-party candidates often have to circulate petitions, get thousands of signatures and pay people to get it all done. “That adds up pretty fast when you’re trying to wage a campaign on a fifty-state level,” says Korte.

But as America’s two-party system has become entrenched, it’s left some voters behind, according to Scot Schraufnagel, a political scientist at Northern Illinois University who also joins the podcast. “The Trump crowd is not the same as the John McCain crowd, right? Those are completely different parties and to have to put them all under one umbrella is really a shame,” he says.

Outsider candidates have faced criticism that they pull votes away from mainstream candidates. When Nader ran against then-Vice President Al Gore and George W. Bush in 2000, the entire race came down to just 537 ballots in Florida, a state where Nader got over 97,000 votes. Given how close margins were between Biden and Trump in some states in 2020, a similar scenario could play out this year.

One group, No Labels, is trying to grab those disillusioned voters, framing itself as an alternative to both Biden and Trump—though it doesn’t have a presidential candidate of its own yet. Ryan Clancy, the group’s chief strategist, like Nader, rejects the spoiler narrative. “One of the things voters across the political spectrum should be pretty outraged about is the extent to which both parties have tried to demonize all these independent voices and to try to keep them off the ballots,” he says.

TranscriptSaleha Mohsin: With every passing primary, it’s looking more and more like the US election is going to play out like Groundhog day… and voters are not excited about it.

Dennis Hoagland: Biden and Trump, too old.

Sandy Neville: We need a new generation in there.

Rob Christenson: We need to look to the future.

Steven Larson: I want a change. A fresh face.

Mohsin: At least, those voters weren’t. We spoke to them in Iowa last month.

But it isn’t just anecdotal. I asked my colleague Gregory Korte about this—he’s been covering political campaigns for more than two decades:

Mohsin: Have you ever seen as many disillusioned voters as we have now?

Gregory Korte: No, and it's really remarkable.

Mohsin: Analysts have even come up with a term for this:

Mohsin: What’s a double hater?

Korte: [laughs] A double hater is a term that pollsters use for people who have an unfavorable opinion of both Joe Biden and Donald Trump. In our Bloomberg News Morning Consult poll, there are about 18 to 20 percent of the electorate.

Mohsin: That’s one in five swing state voters who don’t like either candidate.

Korte: Other polls have that number as high as 30, 35 percent.

Mohsin: One big reason? Just how old both Biden and Trump are.

Korte: We have two septuagenarian, octogenarian candidates that have run before. Americans, they're they're wondering, why don't we have other options?

Mohsin: With all of this fatigue around a Trump-Biden rematch this year, some people are wondering if this cycle has created an opening for a third party candidate.

I asked Ralph Nader—who famously ran for president outside the two major parties four times. Does he think an outsider candidate has a shot in 2024?

Ralph Nader: No because most Americans, they've been taught from elementary school that only one of two nominees can win: Democrat, Republican, so they want to be with a winner.

Mohsin: What’s made even Ralph Nader doubt the possibility of third party success… in an election when voters are begging for another option? And could anything make 2024 different?

From Bloomberg’s Washington bureau, this is the Big Take DC podcast. I’m your host, Saleha Mohsin. Today on the show: America’s Third Party Problem.

These days, it’s something of a given that the Democratic and Republican parties hold all the chips in national politics.

But it wasn’t always that way.

Nader: Third parties changed America in the 19th century.

Mohsin: That is the voice of Ralph Nader. Many remember him as a perennial third party candidate.

Nader: They were first out of the box against slavery, first for women right to vote, first for right to organize unions, on and on, Social Security, Medicare started with third parties and the major parties picked it up.

Mohsin: That spirit, of pushing the government to champion new issues, is what first led Nader to run for president. He’d spent his career as a consumer advocate, and he told me, he didn’t think the two main parties represent American voters.

Nader: Look where they get their money from. The bulk of the money comes from the business community. The countervailing powers are gotten very weak. The unions have gotten weaker. Consumer groups can't keep up and there's nothing to counteract the swarms of lobbyists.

Mohsin: Nader hoped he could carry on that mantle of dissent. He first ran as a third party presidential candidate in 1996, representing the Green Party. He says that the roadblocks were endless.

Nader: It's the hardest democracy, so called, in the Western world, just to get on the ballot. It was like climbing a sheer cliff with a slippery rope.

Mohsin: Democratic and Republican candidates get on the ballot pretty much by default. Third parties, on the other hand, often have to circulate petitions and get thousands of signatures… just to have their names appear on the ballot.

And that has to happen on a state-by-state level. Getting those signatures takes a lot of volunteers—or money to pay people to do the work.

Nader: State by state, millions of signatures. And the Democrats would pick at them and try to disqualify them and say, ‘well, the, this letter didn't comport with the name, et cetera.’ And it exhausted us.

Mohsin: Unlike some other third party candidates like Ross Perot, who could use his personal wealth to fund his campaign—Nader relied primarily on small dollar donors.

Nader: We filled Madison Garden with $20 entrance to raise money.

Mohsin: Third party candidates don’t qualify for federal campaign funds like the two main parties.

When Nader ran for president in 2000, he knew if he got enough votes, he could qualify for funding for the next cycle. So he had to play the long game:

Mohsin: When you launched your campaign in 2000, how likely did you think your chances were of winning?

Nader: Well, we were going for the 5 percent level. If we could get 5 percent or more, then in the next four year cycle, we could qualify for federal campaign funds and try to go higher.

Mohsin: For Nader, that long game goes long past his own political ambitions.

A persistent third party effort could at least urge the major parties to take up issues they might have overlooked.

Nader: But in the last few decades, that hasn't worked. The major parties are so smug and arrogant that they don't listen to third parties anymore.

We're losing a lot in this country by not providing more voices and choices on the ballot, which most Americans want, they don't just want, uh, one Democrat and one Republican.

Mohsin: Nader has a point. As America’s two-party system has become so entrenched, it’s left many voters behind.

Scot Schraufnagel: Right now, the Democrats and Republicans are trying to be these catch all parties that represent everybody's point of view in their, you know, on the left or the right, and they don't.

Mohsin: Scot Schraufnagel is a political scientist at Northern Illinois University. He’s been studying third parties on and off for his entire thirty year career.

Schraufnagel: The Democratic Party is really two different parties at least, you know, and same could be said for the Republican Party. The Trump crowd is not the same as the John McCain crowd, right? Those are completely different parties, and to have to put them all under one umbrella is really a shame.

Mohsin: It’s particularly a shame, he says, because the current system, with its two poles, doesn’t represent the position of most American voters, who fall near the center.

And over the past few decades, ballot access laws have made it harder and harder for new groups to gain a foothold.

Schraufnagel: All of these laws were written in a purely self interested fashion to try to eliminate third party competition.

Mohsin: Back in the days that Ralph Nader yearns for, when third parties had a real seat at the table, political parties were a lot more in flux than they are now. Voting blocs kept realigning.

Korte: We're in a similar sort of period now.

Mohsin: That’s Gregory Korte, a national politics reporter at Bloomberg News.

Korte: With Republicans reaching out to non college educated blue collar voters that traditionally had voted Democratic. Conversely, you have some, more white collar educated workers who used to be Republicans now voting Democratic. You would think that there might be some room for a third party to get in there.

Mohsin: And a handful are trying. You might’ve heard the super-PAC ad for Robert F. Kennedy Jr., that aired during the Superbowl. The ad echoed his uncle’s popular 1960 campaign with its nostalgic visuals and sound—

Ad: Kennedy, Kennedy, Kennedy…

Mohsin: Or you may be familiar with Cornel West, a long-time political activist, who’s running as an independent.

But there’s one new group that’s gotten a lot of buzz this year, by trying to do things differently. No Labels. It’s trying to grab all those disillusioned voters in the middle.

Just listen to their chief strategist, Ryan Clancy, lay out their sales pitch in an informational video… it isn't about what No Labels supports, it's about what they don’t support:

No Labels ad: We worry the two major political parties might leave us with no good choices. We worry they might force us to vote for the least bad option.

Mohsin: No Labels is trying to upend the traditional outsider approach...

Instead of leading with a compelling candidate or platform, it’s saying: we’re going to offer you an option that’s not Biden, and not Trump. But who that option is going to be, and what they support? They haven’t actually said. They’re waiting until after Super Tuesday in March.

Korte: We are sitting here in February. There's an election in November and we don't know who the No Labels candidate is going to be, whether there will be one.

This is an organization that says it's going to run, or would like to run a candidate for president one time. They're not interested in necessarily long term party building, and they're not interested in running candidates for other down ballot races.

And one of the big questions for No Labels is, is there enough passion in the center?

Mohsin: No Labels’ chief strategist, Ryan Clancy, who you heard in that ad, he thinks so. We spoke to him this week, while he was in transit.

Ryan Clancy: An independent wouldn't be able to win if either party was able or willing to put forth choices that most of the public found appealing. They have been unable to do that. Even though the vast majority of the public has been signaling for well over a year, they don't want this rematch.

We see an opening unlike any other that we've seen in modern American history for an independent ticket. I mean, ultimately, if the public didn't want this, they wouldn't be signing the petitions, but they are signing them in droves.

Mohsin: He told us No Labels has already gotten over a million Americans to sign petitions to get them on the ballot.

But if you ask political scientist Scot Schraufnagel… saying you support another option is very different from VOTING for another option.

He says, without structural changes to the way US elections are run—and more grassroots third party momentum—No Labels, RFK Jr., none of these guys have a shot.

Schraufnagel: Success is not going to come to any of them, but they can be a spoiler, and they can, you know, throw the election to one or the other candidate.

Mohsin: Coming up: the bogeyman of the third party spoiler. If none of these outsiders can win in 2024, could they still shape the outcome of the race?

Ralph Nader’s name has gone down in history—not so much because of his passion for consumer advocacy, but more because of the 2000 presidential election.

Here’s how cable news at the time covered his campaign, somewhat ominously…

ABC: Ralph Nader campaigning in Madison today, despite mounting criticism that he might cost Al Gore the election…

Mohsin: Nader ran against Al Gore and George W. Bush. The entire race came down to just 537 ballots in Florida—a state where Nader got over 97,000 votes. Many of his critics say that he spoiled the election for Gore. That’s an idea that he rejects.

Nader: They don’t call each other spoilers, the Republicans and Democrats. Everyone has an equal right to run for election. Then they have an equal right to get votes from one another and none of them should be called spoilers. We're trying to do something about spoiled politics to begin with.

Mohsin: Nader argues that many of his voters would’ve stayed home if he hadn’t run. That he, and other third party candidates, mobilize people who feel left out of the political system. And there’s evidence that that’s true.

But data on the 2000 race also suggests that if Nader hadn’t run, enough of his voters would’ve gone for Gore to change the outcome of the election. And so far, it’s looking like a similar dynamic could play out when it comes to 2024.

My colleague Gregory Korte told me, even a centrist group like No Labels, which is aiming to capture moderate voters from both parties, would likely pull more Biden supporters.

Korte: Donald Trump supporters are so much more loyal and so much more committed. Whereas Biden supporters, a large part of the Biden coalition in 2020, remember, was independents and even some more liberal or moderate Republicans who had had enough of Donald Trump, had seen enough, are sort of realigning away from the Republican Party and went into the Biden coalition, but were never really huge fans of Joe Biden. And the feeling is among Democrats that No Labels poses a big threat to Biden's appeal to that segment, that middle of the road, business oriented Republican segment.

Mohsin: Even Nader seems to see No Labels that way.

Nader: Well, who knows what it is. They don't have a candidate. They don't seem to have an agenda. All they do is irritate the Democratic party.

Mohsin: We asked the chief strategist at No Labels, Ryan Clancy, about this.

Clancy: We just disagree with this basic premise that some of our critics try to advance to suggest that independent one) could only be a spoiler, and two) it could only spoil in favor of, former President Trump. Frankly, all these attacks against us that we would inevitably a spoiler, is in our view, a lot of noise about protecting the established parties’ political turf. And I, I think one of the things voters across the political spectrum should be pretty outraged about is the extent to which both parties have tried to demonize all these independent voices and to try to keep them off the ballot.

Mohsin: The trouble is, voting in the US might be a zero-sum game—a vote for No Labels is one less vote for Biden or for Trump. And that shapes the way people act in the voting booths.

Korte: Voters do tend to be strategic, they're trying to figure out how much does my vote matter? If it doesn't really matter, if neither of the two major party candidates needs my vote, then maybe I'm a little bit more free to vote for a third party candidate just to send a message. But if voters get into the polls in November and sense that it's close, then some of this third party support that we're seeing right now might dissipate.

Mohsin: It’s something that even Ralph Nader admits.

Mohsin: Do you see the seeds for a viable third party candidate having already been planted, where we might see some of this happen in 2024?

Nader: No, because most Americans, when they're asked, do you think we should have a viable third party? They come in around 60 percent. But they don't vote for a third party because they've been taught from elementary school that only one of two nominees can win, Democrat, Republican, so they want to be with a winner.

I had people telling me in my campaigns, ‘Ralph, we really like what you stand for, we like your books and articles and testimony and all the laws you help pass to protect health and safety. But you have to excuse us, we want to be with a winner.’

Mohsin: Major donors see this, too. And without their support, it’s unlikely a third party could gain enough traction to take on the two-headed beast of American politics.

Korte: The problem with trying to have a third party IPO, if you want to think of it that way, if you want to start a third party and say, ‘Okay, I want people to invest in this,’ you need some seed capital, but where are those investors going to come from if they don't see a path to victory?

The big money donors, the kind of money that goes to super PACs, if you're a billionaire and you are spending money on political contributions, you didn't get to be a billionaire by throwing good money after bad. Right? They want to see a return on investment. And frankly, that return on investment comes from the two major parties.

Mohsin: Thanks for listening to the Big Take DC podcast from Bloomberg News. I'm Saleha Mohsin.

This episode was produced by Julia Press and Naomi Shavin. It was fact-checked by Tiffany Tsoi.

Blake Maples is our mix engineer. Our story editors are Caitlin Kenney, Wendy Benjaminson, and Michael Shepard. Nicole Beemsterboer is our Executive Producer. Sage Bauman is our Head of Podcasts.

Thanks for tuning in. I’ll be back next week.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.