Jun 16, 2021

Lagarde Takes Bolder Tone in Setting Agenda for Stimulus Talks

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde is getting tougher with the institution’s unwieldy group of 25 policy makers over the agenda for monetary stimulus.

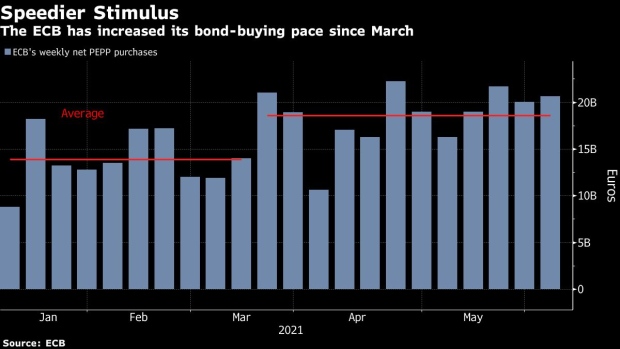

The decision last week to keep emergency bond-buying at elevated levels was heavily influenced by comments Lagarde made in Lisbon three weeks earlier, when she said it’s “far too early” and “actually unnecessary” to think about reducing stimulus, according to officials familiar with the matter.

Policy makers decided it would be economically damaging to slow purchases just yet after those remarks, the officials said. A spokesman for the ECB declined to comment.

The strategy marks a change of tack for Lagarde, who took over in 2019 promising to listen first and build consensus. While she has mostly achieved that, it arguably led to a delayed monetary response at the start of the pandemic, and confusion this year over whether the Governing Council would react to rising euro-zone bond yields.

It could set the tone for the next phase of the crisis, in which she’ll need to engineer a smooth exit from emergency measures while deciding how much stimulus should be delivered with older tools. The ECB’s September meeting, when it will have a new round of economic forecasts and a more-entrenched recovery -- and when inflation is likely to be above target -- will probably be the next big test.

The Lisbon approach has more in common with her predecessor Mario Draghi’s tactic of using public events to tell economists and investors his preferred action, fueling expectations that he later argued the Governing Council couldn’t afford to disappoint.

That helped him push through groundbreaking policies such as quantitative easing -- though it also led to tension and ultimately a failed but significant revolt at the end of his term when he resumed QE after a pause.

Portuguese Pushback

Before Lagarde’s comments in the Portuguese capital, momentum had been building for a vigorous discussion by the Governing Council over whether to slow bond-buying. With coronavirus infections dropping and the economy reopening, the case was being put that the region might need less monetary support.

Economists and investors, who had been split on whether purchases would be slowed, revised their predictions after she spoke and after colleagues including Bank of France Governor Francois Villeroy de Galhau followed with similar messages.

Lagarde ultimately won support for the decision to keep bond-buying at a “significantly higher” pace than in the first months of the year, though there was disagreement over some of the detail.

Differences of opinion within the Governing Council over the next step are again already bubbling to the surface. Some members used last week’s meeting to highlight upside risks to the inflation outlook, and those views were echoed in public remarks this week.

Draghi handled such dissent during his 2011-2019 presidency by increasingly controlling the terms of the debate. Most famously, his “whatever it takes” pledge in 2012 in London forced policy makers to adopt an unlimited bond-buying program just six weeks later to stem the region’s sovereign debt crisis.

He laid out the conditions for QE in Amsterdam in April 2014, and declared at the Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole symposium four months later that those conditions had been filled. The Governing Council approved large-scale asset-purchases in January 2015.

Now Lagarde is also saying more bluntly and more publicly what she thinks should be on -- or off -- the agenda. At her press conference last week, she was asked when the ECB will decide how it exits crisis mode.

“I might just very well refer to my Lisbon line,” she replied. “It’s too early, it’s premature, it’s unnecessary to discuss those longer-term issues.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.