Apr 17, 2024

Mass Coral Bleaching Is Latest Sign of Incredibly Hot Oceans

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- This is from the Green Daily newsletter. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

Once vibrant corals turning bone white highlights something scientists have been saying for years: the oceans are heating up dangerously.

This week, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration announced a global coral bleaching event. Too much heat is the main cause of coral bleaching — and there are more worrying signs as the latest ocean-surface readings show temperatures are on the rise.

Read more: Heat Stress Is Plunging the World’s Coral Reefs Into Crisis

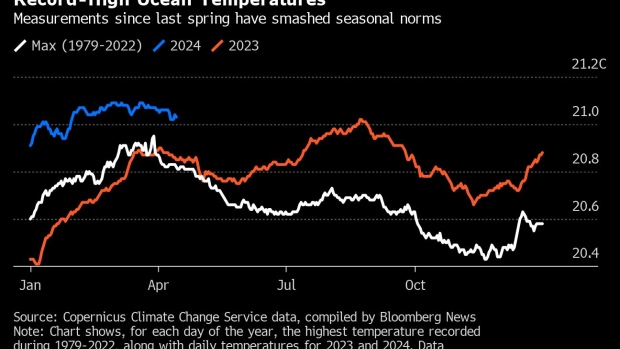

Every day, for more than a year — barring a tiny blip last spring — the global average sea-surface temperature has been at a record seasonal high in data that go back to 1979. And those historical records haven’t just been narrowly surpassed, they’ve been obliterated.

“This is big,” said John Abraham, professor of thermal sciences at the University of St. Thomas. People are realizing just “how important the oceans are as the measurement metric for climate change.”

Hotter oceans matter for all sorts of reasons beyond their impact on coral reefs. They exacerbate sea-level rise as warmer water expands. They restrict the supply of oxygen to marine life and are pushing fish toward the earth’s poles or deeper waters. They’ve been linked to the rise of marine bacteria called Vibrio, which can cause vibriosis in humans, bringing symptoms such as fever, diarrhea, vomiting, and, in some cases, it can kill. And last year, high sea-surface temperatures helped push scientists to raise their forecast for Atlantic hurricanes.

And that’s not all. Warmer ocean — and air — temperatures are generally expected to reduce sea ice. That’s not only bad news for emperor penguins. It’s feared melting ice will help weaken what’s known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC — a system of currents that play a crucial role in regulating the planet’s climate.

Read more: Record-Smashing Heat in the World’s Oceans, Explained: QuickTake

So what’s behind these unprecedented readings?

More than 90% of the extra heat in the planet’s climate system that’s caused by human-made global warming is in the ocean. So as we continue to pump billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year, temperatures are going up.

But the readings seen over the last year suggest something more is going on. The global average sea-surface temperature tends to peak in March — the end of summer in the Southern Hemisphere, which contains the most ocean. Last year, that pattern was broken, with temperatures setting a fresh all-time high in August, and that was breached again earlier this year.

Abraham attributes half of the recent heat to human-made, long-term “slow” global warming. Another big chunk, roughly a third, can be pinned on El Niño, he said. That then leaves about 20% that scientists are still trying to nail down.

There have been plenty of theories. Over the past year, experts have discussed slowing windspeeds, which impact both the mixing of ocean waters and the amount of Saharan dust carried over the North Atlantic. This typically protects the waters below from solar radiation. An environmental rule known as IMO 2020 aimed at slashing vessels’ sulfur emissions has also been highlighted. Sulfur emissions are generally known to have a cooling effect by making clouds brighter and reflecting sunlight — but clarifying the relationship with ocean temperatures can be tricky.

Joel Hirschi, associate head of marine systems modeling at the UK’s National Oceanography Centre, broadly agrees with Abraham’s breakdown. But even if the bulk of the heating is easily explainable, “it doesn’t make it less worrying,” he said. It’s what’s expected from global warming. And it’s fair to believe that in the next couple of years, the temperatures seen in 2023 and 2024 are going to “be beaten again.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.