Apr 2, 2024

Oil Giant Caught in Middle as Bulgaria Unpicks Russian Ties

, Bloomberg News

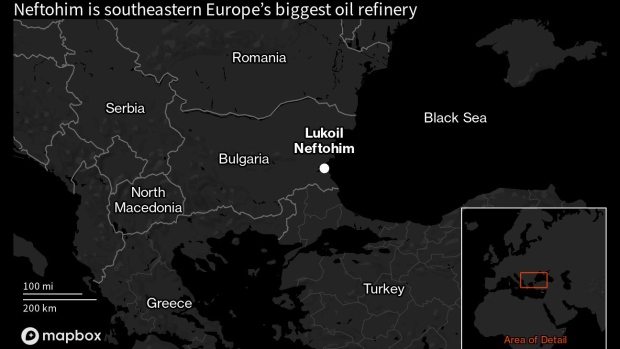

(Bloomberg) -- It’s hard to miss Lukoil in Bulgaria. Its sprawling oil refinery near the Black Sea coast, surrounded by fields of freshly ploughed soil, dominates the area. A quarter of the people in the nearby town of Kameno either work there or have ties to the plant. The Russian company also has more than 220 gasoline stations in the country.

Yet the peaceful and lucrative co-existence between Lukoil and the European Union’s poorest outpost was broken when Vladimir Putin attacked Ukraine a little over two years ago. Now, decades of good business between Bulgaria and Russia face a moment of reckoning as Lukoil looks at selling up and leaving because of what it calls political pressure.

Dismantling ties with Russia more than three decades after the end of communist rule would complete Bulgaria’s shift to embrace the EU and NATO allies and mark a stark contrast to Hungary and Serbia.

Key to that is for the Lukoil Neftohim refinery to be taken over by “a reputable international company” either from Europe, the US or the Gulf, Finance Minister Assen Vassilev said. Opponents of Lukoil say the Russian giant’s network of influence runs deep into Bulgaria’s political and business elite.

“We need to make sure that the business would operate responsibly in the country and would not be used to influence politics,” Vassilev said in an interview in Sofia. “We are making sure that we do not depend for our critical supplies on a country that sees us as unfriendly.”

Unpicking ties with Russia hasn’t been easy, though, and faces some popular opposition. Bonded by history, a related language and the Orthodox religion, Bulgaria has long been defined by its division between Russophiles and Russophobes.

The nation won independence from Ottoman rule in 1878 in the Russo-Turkish war, an event commemorated with a national holiday every March 3. Locals lay flowers at monuments, including the statue of Tsar Alexander II in Sofia. It was then the closest ally of the Soviet Union during communism, nicknamed the 16th republic because former dictator Todor Zhivkov tried to join the USSR.

Just a year before Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007, Russia’s ambassador to the bloc said that it would be useful to have a “Trojan horse” inside the alliance. Bulgaria was solely dependent on Russia for energy.

While the push against Russia is winning points for Bulgaria among its western allies, it’s caused unease in Kameno near the city of Burgas.

Some locals blame Ukraine for resisting Putin and risking an ongoing war they say could spill over from across the Black Sea. Meanwhile, they speak fondly of Lukoil Neftohim, which employs about 1,300 people. They talk of the free supplies kids get on the first day of school and for paying competitive wages. They fear the good days will soon be over.

“People are getting scared — it’s hard to find a job if you’re older,” said Hiulia Alieva, who runs a flower and gift shop in Kameno. “People fear the new owner at the refinery will keep some operations but aren’t sure about the rest. The older people also talk about the war, how it will come here.”

President Rumen Radev, who has repeatedly refused to provide military aid for Ukraine and has questioned EU sanctions toward Russia, has rebuked the effort to oust Lukoil. It was on his watch that ministers negotiated for the refinery to pay tax in Bulgaria.

The nationalist Revival party, whose support has surged in recent years to become the third-largest party ahead of another election, said the plan is simply to curry favor with the Americans.

“The war came and now it is very trendy for politicians to fight with Russia, so they started talking about this,” said Deyan Nikolov, Revival’s secretary in Sofia, adding he didn’t believe that Lukoil wielded political influence in Bulgaria. “Lukoil here is quite clearly just a business.”

In reality, staying in Russia’s orbit became untenable after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Bulgaria had its gas supply shut off by Russia after refusing to pay in rubles, causing trouble for a nation solely dependent on Gazprom PJSC. In October, it angered Hungary and Serbia by imposing a tax on Russian gas transiting its territory via a pipeline before backtracking.

The parliament in Sofia has since approved a ban on Russian oil imports and the country is looking at alternative supplies for a vital nuclear plant that’s fed by Russian fuel.

On the political front, the country joined other nations in expelling Russian diplomats, having sent dozens back home on suspicion of espionage. It expelled the head of the Russian Church in Bulgaria and two other clerical employees.

Albeit long after other countries, Bulgaria has officially started sending weapons to Ukraine. In the backdrop was intensifying Russian cyberwarfare aiming to disrupt Bulgaria’s shift westward and plans to adopt the euro next year.

The US welcomed Bulgaria’s response, calling its role critical. “Bulgaria has stepped up in important ways, including by hosting a multinational NATO Battle Group, by providing a range of assistance to Ukraine, and by standing firmly in the face of Russia’s dangerous threats, lies, and provocations,” Kenneth Merten, the American ambassador in Sofia, said in an interview last month.

The pivot wasn’t lost on Lukoil. In December, the company said that because of the pressure it is facing in Bulgaria, it had decided to review its strategy, including the potential sale of the business.

The revision of its plans “is a consequence of the adoption by the Bulgarian state authorities of discriminatory laws and other unfair, biased political decisions toward the refinery, which have nothing to do either with the civilized regulation of a large business or with increasing the revenue part of the country’s budget,” the company said.

The shift in Bulgaria reflects the change in the political narrative after five elections since April 2021 highlighted the debate over the nation’s orientation. A sixth vote, after another spate of political turmoil and the collapse of the latest government, could boost support for pro-Kremlin parties.

Indeed, the plan to push out Lukoil has backers who might ordinarily have been expected to side with the company, though are now blowing with a different prevailing wind.

One is Boyko Borissov, a former bodyguard who became prime minister and ran Bulgaria on and off for 11 years. Borissov used to court Putin, giving him a puppy when he visited in 2010 to sign a gas deal. He has called Valentin Zlatev, the former head of Lukoil in Bulgaria, his friend.

A year before Russia’s invasion, Borissov’s government forced the construction of the pipeline securing Russian gas supplies to Serbia and Hungary, bypassing an existing route via Ukraine. He was slammed for having served the Kremlin with the project while for years he delayed building routes to alternative sources.

Another supporter of Lukoil’s ouster is Delyan Peevski, a member of parliament and a former media mogul sanctioned by the US for his extensive role in graft in Bulgaria.

“Russia’s criminal regime got richer under the benevolent gaze of the Bulgarian government,” he said in November, urging to end an exemption from EU sanctions. “The Bulgarian citizens were only harmed from this derogation.”

Lukoil hasn’t said that it’s actually proceeding with the refinery sale, while Litasco SA, the Russian company’s international marketing and trading firm that officially owns the plant, declined to comment when contacted for this story.

Finance Minister Vassilev, though, is convinced the company is already looking for a buyer and Bulgaria does and will have the political conviction to make it happen.

“Bulgarians like a good deal,” he said. “Diversification provides a good deal for the country, a good deal for the industry. Given the choice between ideology and a good deal, we’ll always take the good deal.”

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.